The metamorphosis of Capitalism from a rejection of feudalism and rental, into encompassing it | Knowledge is Power

Capitalism evolved as a rejection of feudalism, based on rental, as an economic policy. It was based on exploitation of labour. Now it has come full circle, to include rental, and speculation.

Capitalism evolved as a rejection of feudalism, based on rental, as an economic policy. It was based on exploitation of labour. Now it has come full circle, to include rental, and speculation.

If you are interested in this article, please read it online, where I have added an index and tidied it.

Introduction

I never thought I’d find economics interesting, until I found out that money is made out of thin air by a few random privileged individuals for their own profit, and dispensed to whom they choose.

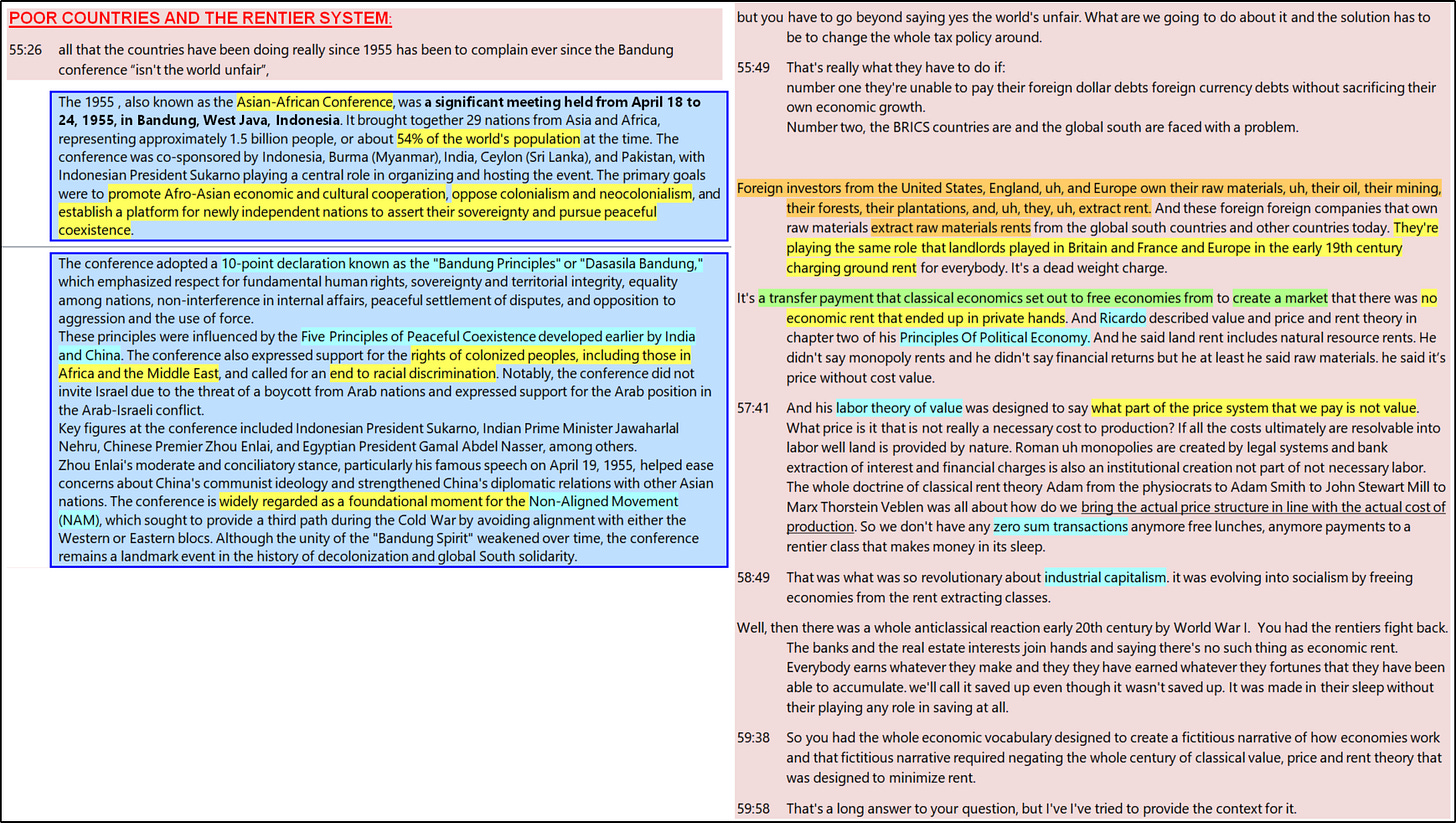

I was fascinated by a discussion by Dr Michael Hudson in The Balance of Payments Illusion: How America Makes Money Without Paying - YouTube.

So I did a dive into what “capitalism” really was. What I found is set out below.

While Dr Hudson’s whole talk is highly recommended, Here are two of the side issues he discussed, which caught my interest, in which he appeared to juxtapose capitalism with “rentier” or rental. So I did a dive into what capitalism actually was. The surprising results are set out below.

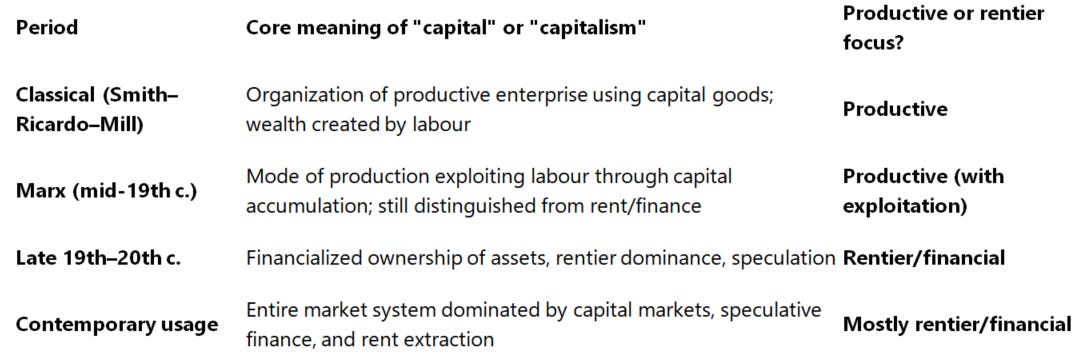

The change of meaning of Capitalism

My question: “Did capitalism originally have a different meaning under classical economic theory, which did not include rentier and stock market trading?“

The answer (ChatGPT):

“Capitalism” in classical economic theory (roughly late 18th to mid-19th century) did not mean what it does today. The original meaning was far narrower, more productive in orientation, and largely excluded the rentier, speculative, and financialized forms that dominate modern capitalism.

Here’s how the meaning evolved:

1. Classical economists’ view (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, etc.)

Capital meant produced means of production — tools, machinery, infrastructure — used to generate new wealth through productive labour.

Capitalists were those who invested in and organized productive enterprise, paying wages to workers and earning profits only through the creation of new goods and services.

The focus was on production, not on passive ownership or financial manipulation.

The “system of capital” was therefore a productive organization of industry, not primarily a financial or speculative one.

Adam Smith, for instance, condemned rent-seeking behaviour and “unearned income.” He considered rent (from landownership) and interest (from lending) as deductions from the wealth created by labour and productive enterprise — not as true sources of value.

Ricardo also drew a hard distinction between:

Profit — legitimate return to productive investment, and

Rent — unearned income arising from ownership of scarce resources, especially land.

2. Absence of the modern financial system

The stock market, joint-stock corporations, and financial speculation as central features of capitalism were either rudimentary or viewed as parasitic by classical thinkers.

Their “capitalism” was industrial and tangible, not financialized.

What we today call “shareholder capitalism” or “finance capitalism” didn’t emerge until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when capital markets began to dominate the economy.

3. Later transformation (Marx and beyond)

Karl Marx was among the first to use “capitalism” as a system-level term — not just “capital,” but a mode of production governed by the accumulation of capital.

He maintained the classical insight that profits arise from productive labour, but extended it to argue that capital itself exploits labour by appropriating surplus value.

However, Marx, too, considered rent and speculative finance as non-productive or fictitious capital.

4. 20th-century shift

By the early 1900s, especially with thinkers like Thorstein Veblen and John Maynard Keynes, the meaning of capitalism expanded (and, in many ways, inverted):

The rentier (someone living off returns from property, stocks, or bonds) became central to the actual operation of capitalist economies.

Speculation and financial intermediation grew dominant, detaching the term from its classical, productive base.

Keynes famously argued for the “euthanasia of the rentier”, viewing rentier income as socially useless and destabilizing.

5. Summary of meaning shift

So originally, “capitalism” referred to a productive system of industrial capital, not to financial speculation, rent extraction, or stock market manipulation. Those were, in fact, considered antithetical to the healthy functioning of a capitalist economy in classical theory.

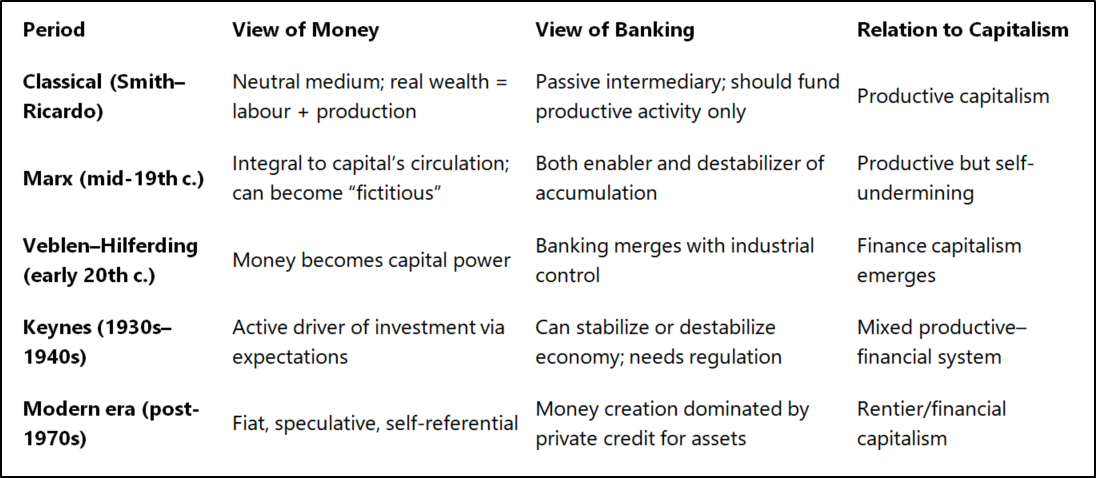

The co-evolving views of banking and money

The understanding of banking and money was one of the key dividing lines between productive capitalism (as conceived by the classical economists) and the later financialized capitalism that supplanted it.

Let’s trace how the perception of money, credit, and banking evolved alongside the changing meaning of capitalism.

1. Classical political economy (Smith, Ricardo, Mill): Money as neutral and banking as auxiliary

Money’s role:

For the classicals, money was a veil over real economic activity. It facilitated exchange but was not itself a source of wealth or production. Real wealth was created only through labour applied to capital and land.

Banking’s role:

Banks were viewed as intermediaries, channeling existing savings into productive investment.

They were not seen as creators of money or credit in their own right.

Their function was limited: to mobilize idle savings and lend them to those who could use them productively (e.g., manufacturers).

Example: Adam Smith

Praised banks when they extended productive credit to merchants and manufacturers.

Condemned speculative finance and paper credit that detached money from production.

He distrusted over-issuance of paper money, fearing it would create bubbles divorced from real value.

Example: Ricardo

Saw money as a commodity, ideally gold or silver, ensuring value stability.

Opposed “inconvertible paper” (fiat money) because it could be manipulated by governments or financiers.

So under classical theory, money was passive and banking was service-like, not creative or profit-generating in its own right.

2. Marx’s analysis: Money and banking as part of capital’s expansion — but with limits

Marx deepened and complicated the classical picture. He identified money and credit as integral to capital accumulation, yet distinguished sharply between:

Productive capital (used in production and generating surplus value), and

Fictitious capital (financial claims on future value, detached from real production).

Key points:

Banks and credit expanded the scale of production by advancing capital before actual goods existed — thereby accelerating capitalism’s growth.

But this same credit system generated instability and crises, as fictitious claims (stocks, bonds, speculative instruments) multiplied faster than real productive capacity.

Marx saw financial capital as a necessary but contradictory feature of capitalism — both enabling and undermining it.

In short:

Marx accepted that money and banking could stimulate productive investment, but condemned the transformation of credit into autonomous, rentier-driven power.

3. Late 19th–early 20th century: The rise of finance capitalism

After industrial capitalism matured, banking itself became central rather than auxiliary.

Joint-stock banks and investment houses began controlling industrial firms, forming cartels and trusts.

The distinction between “industrial” and “financial” capital blurred.

Economists like Rudolf Hilferding (in Finance Capital, 1910) described how the banking sector subordinated industry, creating a new phase — finance capitalism.

Here, profit increasingly arose from financial control, speculation, and ownership, not production.

This was alien to classical and even Marxian views of capitalism’s productive foundation.

4. Veblen, Keynes, and the critique of rentier finance

Thorstein Veblen (1890s–1920s):

Distinguished between “business” (financial manipulation) and “industry” (productive activity).

Condemned bankers and financiers as “absentee owners” who extracted profit without contributing to production.

John Maynard Keynes (1930s):

Reintroduced credit and money as active forces — not mere “veils.”

Recognized that investment decisions depended on expectations and liquidity preferences, making finance central to economic outcomes.

Nevertheless, he too saw the rentier (living off interest, dividends, or bond income) as socially parasitic.

“The euthanasia of the rentier” was his vision of a mature capitalism: banking and finance serving production, not dominating it.

5. Postwar to contemporary era: Money creation and the triumph of financial capital

Post-1945 (Keynesian–industrial balance):

Banks still seen as instruments of national development, subject to regulation.

Credit policy aimed to stimulate productive investment and employment.

Since the 1970s (neoliberal–financialized era):

Deregulation turned money and banking into independent engines of profit.

Banks no longer merely intermediated existing savings — they created money through lending, often for asset purchases (real estate, stocks) rather than production.

Central banks shifted from supporting full employment to protecting asset values and financial stability.

This marked a complete inversion of the classical ideal:

Banking, once the servant of production, became its master.

Money, once a measure of real value, became itself the object of production.

6. Summary: Evolution of views on money and banking

In short:

Classical economics: money = neutral, banking = service.

Marx: money = dynamic part of capital, banking = double-edged.

Modern finance capitalism: money = power, banking = ruler.

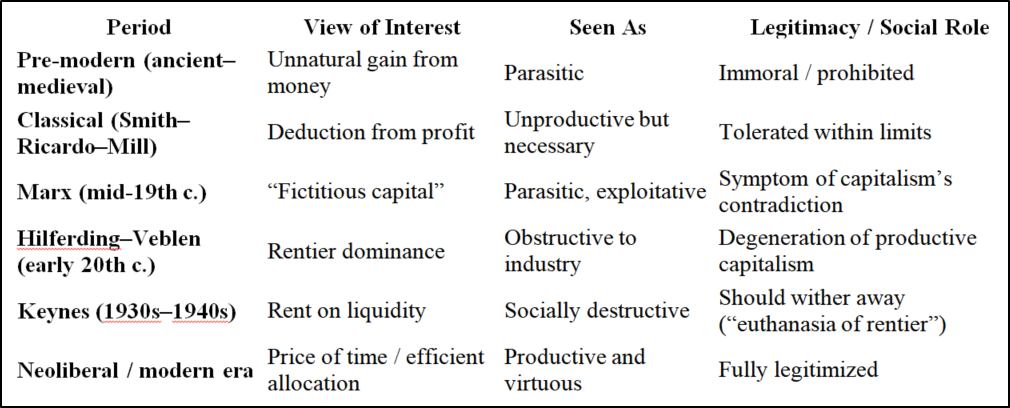

The co-evolution of views of interest charges - rental of money

Interest is the missing piece that ties the whole evolution together. Its meaning and legitimacy shifted dramatically over time, tracking the broader change from productive capitalism to rentier-financial capitalism.

Let’s trace that step by step.

1. Pre-classical and early classical views: Interest as suspicious or parasitic

Moral and religious backdrop:

For most of Western history, interest (usury) was morally condemned.

Aristotle called interest “the most unnatural” of all wealth-getting, because money “begets money” without producing anything.

Medieval Christian and Islamic traditions shared this stance: money was sterile; earning income from lending was exploitation.

This persisted until the late 17th–18th centuries, when commercial society began to justify moderate interest as a reward for risk and delayed consumption — but even then, it was treated as an exception, not a moral right.

2. Classical political economy (Smith, Ricardo, Mill): Interest tolerated but limited — still “unproductive”

The classicals accepted that lending at interest could serve a purpose in organizing production, but they kept a strict distinction between:

Profit: a productive return, earned through organizing labour and capital;

Interest: a derivative, unproductive claim on that profit.

Adam Smith

Treated interest as a deduction from profits — a share given to the lender out of the borrower’s productive gains.

He supported legal limits on interest rates to prevent speculation and usury.

In Wealth of Nations, he classified rent and interest as “unearned” income, tolerated only when they supported productive enterprise.

David Ricardo

Considered the rate of interest to be determined by the rate of profit.

Interest had no independent existence; it merely transferred part of the profit from the industrialist to the financier.

Thus, he too saw the lender as non-productive, participating parasitically in productive surplus.

John Stuart Mill

Echoed this: the lender’s income was legitimate only insofar as it funded real capital formation — not speculation.

Emphasized that “capital is the result of saving,” but saving by itself did not create wealth unless employed productively.

In summary:

Classical theory tolerated interest as a necessary evil of mobilizing capital — but viewed it as a non-productive share of the surplus.

3. Marx: Interest as “fictitious” and rentier power

Marx systematized the classical distinction.

He divided capitalist income into three main forms:

Profit of enterprise (from productive use of capital),

Rent (from ownership of land or natural monopoly),

Interest (from ownership of money-capital).

He defined interest-bearing capital as the purest expression of “money begetting money” (M → M′) — wealth multiplying without production.

The lender has no role in production, yet claims a share of the surplus.

Hence, interest represents “fictitious capital”: a legal claim to future production that may or may not materialize.

The credit system makes this abstraction possible and multiplies it into bubbles and crises.

“Interest-bearing capital is the mother of all insane forms of capital.”

(Capital, Vol. III)

For Marx, then, interest wasn’t just parasitic — it symbolized the ultimate alienation of wealth from labour and production.

4. Late 19th–early 20th century: Rentier capitalism and the institutionalization of interest

By this stage, interest became central to capitalism itself.

The rise of bond markets, joint-stock companies, and corporate finance created entire classes living off interest, dividends, and capital gains.

The “rentier” became a distinct social group — investors, not producers.

Rudolf Hilferding (1910, Finance Capital):

Showed how the merging of banks and industry turned interest from a secondary claim into the dominant organizing principle of capitalism.

Yet he, too, viewed this as a degeneration of productive capitalism into rentier control.

Thorstein Veblen (1890s–1920s):

Distinguished between industrial profits (earned from production) and pecuniary returns (interest, dividends, speculation).

Saw the latter as obstructive — business deliberately restricted production to maintain prices and protect financial returns.

5. Keynes: Interest as socially destructive — call for its euthanasia

Keynes revived the classical and moral critique in modern form.

He argued that the interest rate was not a natural reward for “saving,” but a social convention reflecting liquidity preference — the rent charged by those who hoard money.

In a well-run economy, interest should fall to zero as abundance grows.

“The euthanasia of the rentier, and, consequently, the euthanasia of the cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity-value of capital.”

(The General Theory, 1936)

For Keynes, the rentier was a drag on growth, extracting income without contributing to productive effort — precisely what classical economists had feared.

6. Postwar–neoliberal shift: Interest as “natural” and virtuous

After World War II, financial institutions were regulated, and interest rates were often managed by governments — roughly consistent with Keynesian ideas.

But from the 1970s onward, neoclassical and neoliberal economics reversed the classical stance:

Interest was redefined as the market price of time — a reward for postponing consumption (the “time preference” theory).

Money and credit were “neutral”; saving was “productive” because it funded investment (even though banks create money ex nihilo).

Rentier income, once condemned, was reframed as a legitimate, even virtuous, form of capital allocation.

The result:

The rentier became central again — not as a parasite, but as the supposed engine of efficiency.

Yet in practice, interest extraction returned to the medieval problem: wealth accumulated by lending and speculation, not by production.

7. Summary: How views of interest charging evolved

8. Core trajectory

Originally, interest was morally condemned.

Classical economists reinterpreted it as a small but non-productive claim on profit.

Marx and later critics saw it as the emblem of capital’s detachment from real value.

Keynes tried to subordinate it to social purpose.

Modern economics normalized it, erasing the moral and productive distinctions that earlier economists had drawn.

In short:

Under classical theory, interest was tolerated but regarded as unearned; under modern capitalism, it became celebrated and institutionalized as the engine of growth — even though it no longer corresponds to productive creation of wealth.

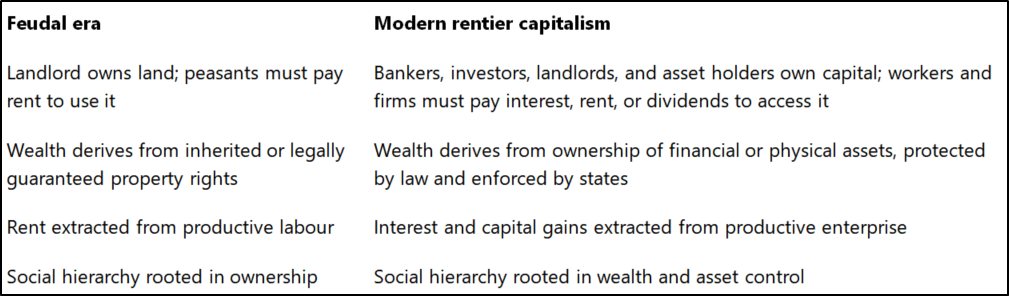

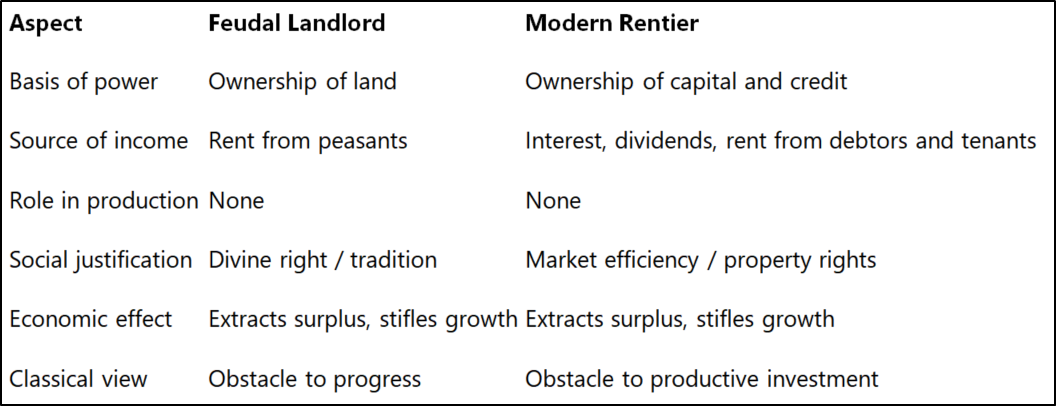

Is rentier a neo-feudal concept?

Yes — the rentier is best understood as a neo-feudal concept, both historically and functionally.

While the term arises in modern economics, the underlying reality it describes — the extraction of unearned income through ownership rather than production — is directly analogous to feudal rent.

Let’s unpack this carefully.

1. Feudal rent: ownership without production

Under feudalism, wealth and power derived from ownership of land and the ability to extract rents or dues from those who worked it.

The lord controlled access to land — the essential means of livelihood.

The serf or peasant laboured productively, but owed a portion of that output to the lord.

The landlord’s income was therefore unearned, based purely on property rights, not labour or enterprise.

In economic terms, feudalism was a rentier system: production and ownership were separate; ownership dominated.

2. Classical capitalism’s break from feudalism

Classical economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo explicitly attacked the feudal rentier structure.

They saw productive capitalists — those who invested in labour and machinery — as the true agents of progress.

Landlords, by contrast, were remnants of feudal privilege who extracted rent without contributing to production.

Ricardo’s Law of Rent was meant to expose how landownership siphoned off economic gains as society developed.

Smith likewise wrote that landlords “love to reap where they never sowed.”

The rise of industrial capitalism was, in part, a revolt against this parasitic rentier class.

3. The rentier in modern capitalism: feudalism reborn

When financial and property ownership came to dominate capitalism — particularly from the late 19th century onward — the old feudal structure quietly returned in new form.

Thus, the rentier economy is a neo-feudal order — not in form (no formal serfdom), but in structure:

Control of access to the means of life (now capital, credit, and housing rather than land)

Legal entitlement to extract tribute (interest, rent, dividends) from those who produce

A self-reinforcing hierarchy protected by the state and legitimized by ideology (“free markets” instead of “divine right”)

4. Marx, Veblen, and Keynes on the neo-feudal character

Marx saw rent and interest as the survival of pre-capitalist relations within capitalism — “fetters” on production.

“The monopoly of landed property is a historical basis of monopoly in capital.” (Capital, Vol. III)

Veblen described rentier owners as “absentee landlords of industry”, controlling production while contributing nothing — a perfect analogy to feudal lords.

Keynes identified the rentier as a socially useless class, a modern equivalent of the idle aristocracy living on inherited claims. His proposal for the “euthanasia of the rentier” was, essentially, a call to complete capitalism’s break with feudal remnants.

5. Why it’s called “neo-feudal” rather than just “financial”

Because in financialized capitalism, economic power again rests on:

Legal privilege (property, patents, intellectual property, control of currency issuance);

Dependence relationships (debt peonage, wage suppression, monopoly pricing);

Rent extraction rather than production.

This creates a hierarchy of rent-collectors and debtors, structurally equivalent to lords and vassals, only now mediated through contracts and balance sheets instead of oaths and manors.

Contemporary critics (e.g., Michael Hudson, Yanis Varoufakis, and some post-Keynesians) argue that the 21st-century economy has become “neo-feudal” because:

Interest, rent, and capital gains dominate national income.

Productive investment is secondary to financial speculation.

Workers and even states depend on borrowing from rentier institutions (banks, bondholders).

6. Summary: rentier as neo-feudal figure

7. Conclusion

Yes — the rentier is fundamentally a neo-feudal class, re-emerging within modern capitalism.

Where feudal lords owned land, rentiers own money, capital, and credit.

Where peasants owed rent in kind, workers and businesses owe interest and rent in cash.

The form changed, but the essence — ownership without labour, privilege without production — remains the same.

Meaning of “investment in labour”

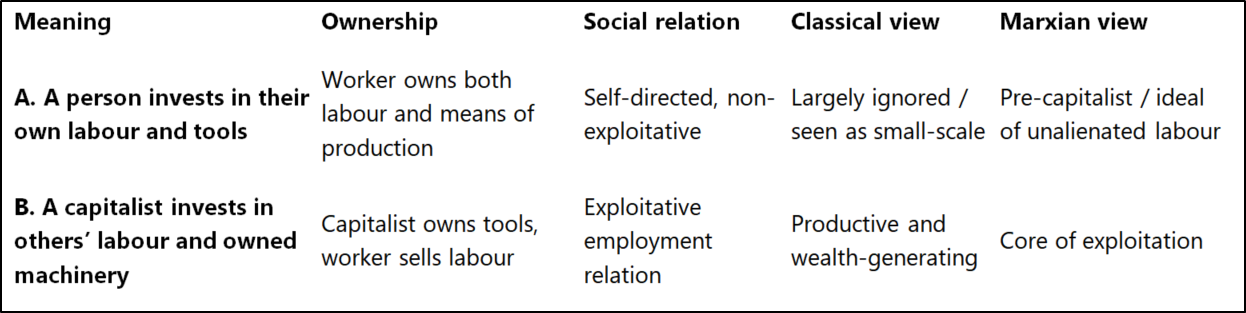

The phrase “invested in labour and machinery” conceals a critical difference between two entirely different relationships to labour:

Capital employing others’ labour (exploitative), and

A person investing in their own labour and tools (self-employment or cooperative production).

Classical economists tended to blur that line — but it’s the line that separates genuine productive work from exploitative capital accumulation. Let’s unpack this carefully.

1. Classical meaning: capital as employing others’ labour

When Adam Smith or David Ricardo spoke of the capitalist “investing in labour and machinery,” they meant the capitalist advances wages to workers and buys machinery to produce goods for profit.

In this system:

The worker sells labour power but owns neither tools nor output.

The capitalist owns the means of production, hires labour, and keeps the surplus (profit) after paying wages.

This was not about a person investing in their own productive activity — it was about commanding the labour of others.

Smith and Ricardo approved of this arrangement not because they thought it moral, but because they believed it increased the “productive powers of labour.” They viewed capital accumulation as the means by which society expanded production.

However, they still distinguished it from rentier income — at least the capitalist, in their view, organized production and risked capital, unlike the landlord or moneylender who merely collected without contributing.

So in classical terms:

The “productive capitalist” was one who employed labour to produce goods — even though that necessarily implied subordination of labour.

2. The missing figure: the independent producer

Classical economists did recognize small artisans, farmers, and shopkeepers who owned their own tools or land — i.e., “self-employed capitalists.”

But they saw them as transitional figures, destined to be absorbed by larger capitalist enterprise. Their existence didn’t fit easily into the labour–capital dichotomy.

Adam Smith wrote of the “self-employing workman” as someone who combined the roles of worker and capitalist, but he treated this as a curiosity — not the core of the system. Ricardo largely ignored them.

Thus, in classical theory, the ownership of one’s own labour and tools was acknowledged but not conceptually central. The economy was modelled around the relationship between owners of capital and owners of labour.

3. Marx’s intervention: making the distinction explicit

Marx made that distinction foundational. He defined capitalism precisely as the separation of labour from the means of production.

Under pre-capitalist or small-producer systems, the worker owned their tools or land.

Under capitalism, the worker was dispossessed, forced to sell labour power to someone who owned the means of production.

That’s what he meant by the “double freedom” of the worker:

Free from personal bondage, but also free from ownership of the means to live.

So yes — “investment in labour and machinery” in capitalist terms means purchasing or commanding others’ labour, not empowering one’s own.

Marx considered that shift — from self-directed production to wage labour under capital — the root of exploitation.

4. Later reinterpretations: ownership of one’s own labour re-emerges

By the late 19th and 20th centuries, a few traditions tried to restore the distinction you’re pointing to:

Cooperative and mutualist economics (Proudhon, later guild socialists): emphasized workers owning their own tools and organizing production collectively.

Distributism (Chesterton, Belloc): argued for a society of small proprietors, each owning their means of livelihood, to prevent both capitalist and socialist centralization.

Modern cooperative movements (e.g., Mondragón in Spain): reassert that labour’s own investment in itself — not capital’s investment in labour — defines ethical and sustainable production.

These are all, in a sense, attempts to reclaim the classical idea of production, but to reattach ownership to those who actually perform the work.

5. So what the phrase really means

When classical economists say “invested in labour and machinery,” it can mean two very different things:

The classical notion of “investment in labour” does not imply self-ownership of labour — it presumes the opposite.

6. Broader implication

That linguistic slippage — treating “investment in labour” as a productive virtue — is one of the ideological pillars of capitalism. It disguises the fact that:

Labour itself cannot be “invested in” without being owned, rented, or subordinated,

The true producer (the worker) is portrayed as a factor of production, not as the source of value, and

The “productive capitalist” becomes morally superior to the rentier, even though both rely on ownership over others’ efforts.

In summary:

Yes — under classical economic theory, “investing in labour” meant employing others’ labour, not one’s own.

True ownership of one’s own labour existed only in small-producer or cooperative forms, which capitalism historically displaced.

That distinction marks the line between productive independence and exploitation through ownership.

Would you like me to trace how early socialists and mutualists (like Proudhon and early cooperativists) tried to redefine “capital” so that it referred to tools in the hands of labour, not ownership over labour?

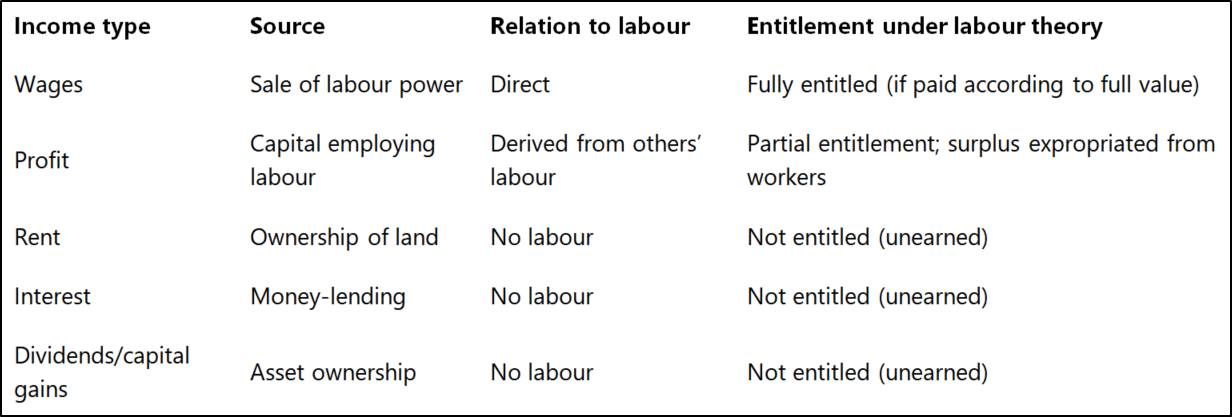

The concept of entitlement to the true value of labour and the union movement

Any full account of labour, capital, and exploitation is incomplete without explicitly considering entitlement to the true value of labour and the union movement. These ideas address precisely the gap left by classical economics: the fact that labour produces value but does not necessarily receive its full share. Let’s unpack this carefully.

1. Entitlement to the value of one’s own labour

This is a concept that arises naturally when you question the classical distinction between “labour” and “capital”:

Classical economists like Adam Smith and Ricardo recognized that labour produces real wealth.

However, they generally accepted that the capitalist, who owned the means of production, was entitled to profit, and that wages were just the “natural price” of labour.

They did not frame wages in terms of labour’s claim to its own product — i.e., the idea that workers are entitled to the full value they create.

This is the conceptual root of labour entitlement: the notion that the worker has an inherent claim to the surplus value they generate.

Marx formalized this in his theory of surplus value:

Profit = value produced by labour − wages paid to labour.

Labour produces more than it receives.

That unpaid portion — surplus value — is expropriated by capital.

Even before Marx, radical thinkers (e.g., Robert Owen, William Thompson) argued that labourers should receive the full fruits of their labour.

So entitlement to the value of labour is both a moral and economic concept: labour is productive, and extracting its surplus without consent is exploitative.

2. The union movement and collective bargaining

The union movement operationalized the principle of labour entitlement in the social and political sphere:

Workers organized to assert control over the terms and returns of their labour.

Unions sought to secure higher wages, shorter hours, safer conditions, and a share in productivity gains, directly addressing the classical imbalance between capital ownership and labour contribution.

This movement challenged the classical economic assumption that the labourer’s share should be dictated solely by the “market rate” of wages.

Some historical notes:

Early industrial Britain (late 18th–19th c.): unions were often illegal; collective bargaining was viewed as “interference with the natural order” — i.e., a violation of classical laissez-faire.

Post-1830s legal reforms gradually recognized the right of workers to organize.

20th century: unions became the primary mechanism for enforcing labour’s entitlement to productivity gains, including through profit-sharing, pensions, and workplace representation.

Thus the union movement is a practical realization of the moral claim that workers should receive the value they create — a direct counterweight to both classical capitalism and rentier appropriation.

3. Entitlement and the critique of rentier and speculative income

Entitlement to labour’s value also highlights the distinction between:

From this perspective, the union movement is the social mechanism asserting the worker’s entitlement, mitigating the structural exploitation classical economics otherwise normalized.

4. Moral and political dimension

The concept of entitlement reframes the question of production:

Classical economics emphasized efficiency, production, and capital accumulation.

Entitlement focuses on justice and fairness: who rightfully owns the value produced?

This aligns with broader movements for:

Minimum wage laws

Social insurance and pensions

Collective bargaining rights

Workplace democracy and profit-sharing

All of these are attempts to align the economic system with the principle that labour should receive its due, rather than merely what the market or a capitalist allows.

5. In summary

Classical economists recognized labour as the source of value but accepted wage as a natural deduction from productivity.

Marx and radical economists argued that labour is entitled to the full value it creates, and that surplus value taken by capital is exploitation.

The union movement is the primary institutional mechanism by which workers claim and enforce this entitlement in practice.

Modern capitalism, especially in its rentier and financialized forms, still largely circumvents these entitlements, allowing ownership-based income to exceed labour-based claims.

Here’s a diagrammatic representation of value flows under three different frameworks: classical capitalism, Marxian critique, and modern financialized capitalism; including labour entitlement and union intervention.

1. Classical Capitalism (Smith/Ricardo)

Labour + Capital → Production → Revenue

│

├─ Wages → Labour (market-determined)

└─ Profit → Capitalist (owner of means)

Labour produces value, but receives only the “natural” wage.

Capitalist receives surplus profit as a reward for organizing production and risking capital.

Rent and interest (if present) are considered unearned and parasitic.

Entitlement of labour: implicitly limited to wage; no institutional enforcement.

2. Marxian Capitalism

Labour + Capital → Production → Revenue

│

├─ Wages → Labour (partial, usually below value)

├─ Surplus value → Capitalist (profit from labour)

├─ Rent → Landowner (unearned)

└─ Interest → Moneylender (unearned)

Labour generates full value; surplus is expropriated.

Rentier income is recognized as non-productive.

Entitlement of labour: theoretically to full value created; in practice denied.

Union movement / worker collectives: attempt to reclaim some or all surplus value via strikes, bargaining, or co-ownership.

3. Modern Financialized / Rentier Capitalism

Labour + Capital → Production → Revenue → Financialized Returns

│

├─ Wages → Labour (often stagnating, below productivity)

├─ Profit → Corporations (often absorbed by shareholding)

├─ Rent → Property/land owners

├─ Interest → Banks / Bondholders

└─ Capital gains / Dividends → Rentier investors

Labour receives a smaller fraction of the value it produces relative to capital owners and rentiers.

Financial institutions dominate, redirecting surplus away from production.

Union movement / entitlement mechanisms: weakened in many countries; bargaining power reduced.

4. Key Takeaways from Diagram

Classical capitalism: profit comes from productive organization; labour’s entitlement limited but stable; rentier income marginal.

Marxian analysis: exposes the structural exploitation — labour produces more than it receives; surplus captured by owners.

Modern financialized capitalism: labour receives even less; rentier and financial claims dominate; entitlement mechanisms (unions, collective bargaining) are weakened but remain crucial for reclamation of value.

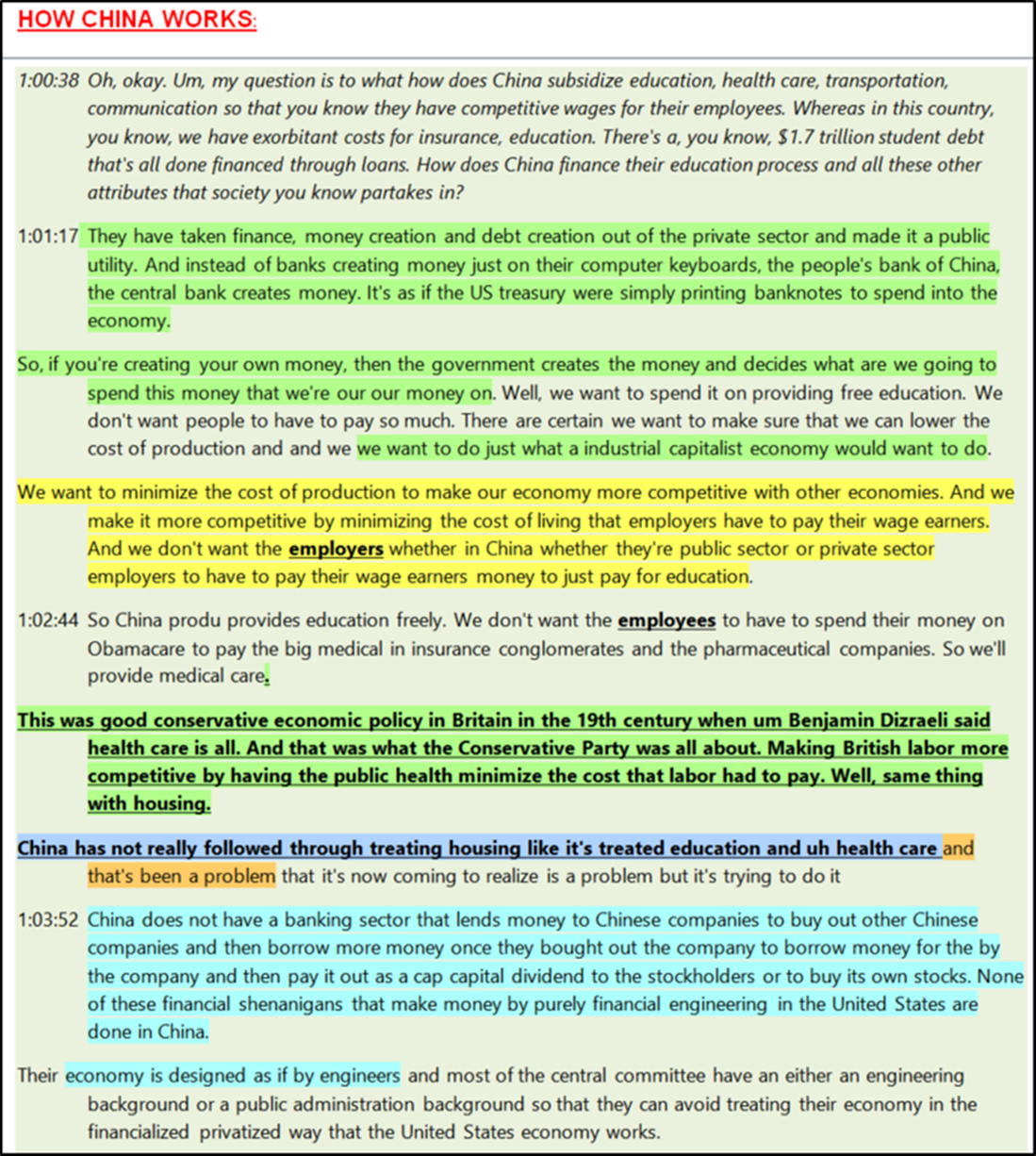

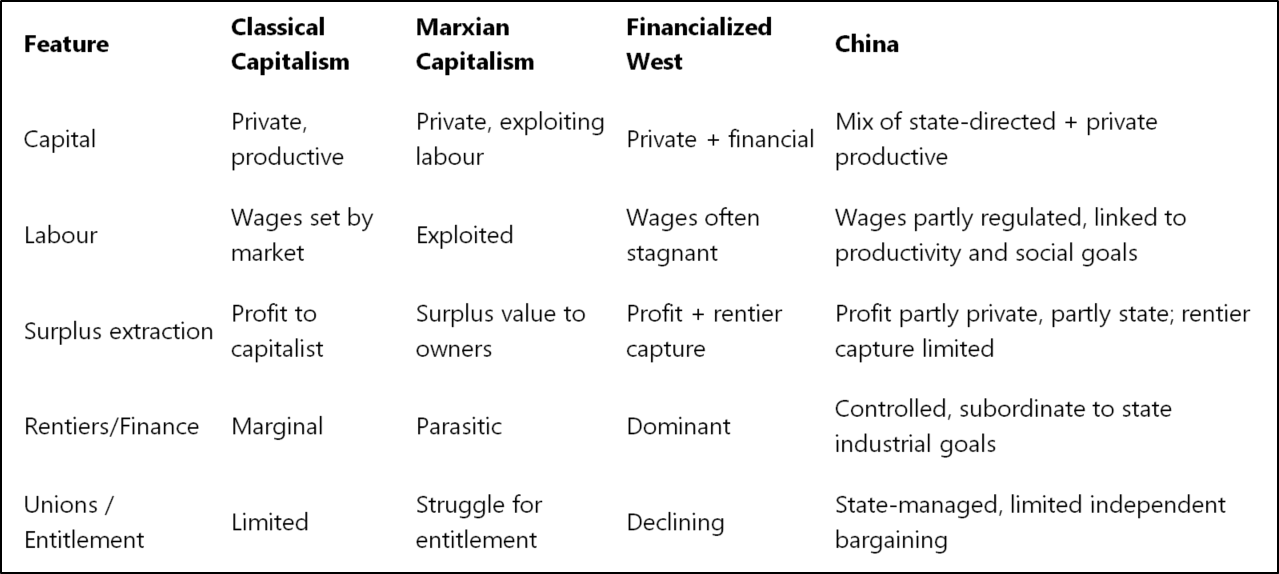

So how does the Chinese system compare"?

The Chinese economic system offers a unique hybrid that combines elements of state-directed capitalism, productive investment, and limited rentier extraction, making it quite different from classical, Marxian, or fully financialized capitalist models. Let’s break it down carefully.

1. Basic structure of the Chinese system

China’s economy can be understood as a mix of:

State-directed productive capital

The state owns or controls the “commanding heights” of the economy: energy, infrastructure, major banks, telecommunications, heavy industry.

Investment decisions are guided by policy goals (industrialization, technological advancement, employment), not purely by profit maximization.

Labour is employed directly by state enterprises or indirectly via state-guided private firms.

Private productive capital

Small and medium enterprises, private manufacturers, and export-oriented firms operate under market rules, generating profit from labour and production.

Unlike in Western financial capitalism, large-scale rentier finance does not dominate the economy.

Limited rentier/financial sector

China has a banking system and stock markets, but financialization is tightly controlled:

Interest rates and credit allocation are guided by the state.

Speculative financial instruments exist, but capital flight and rentier dominance are restricted.

Household debt is rising, but systemic financial speculation is far less central than in Western economies.

2. Labour, wages, and entitlement

Workers are employed in both state and private firms. Wages are typically tied to productivity but are influenced by policy objectives (e.g., regional development, social stability).

The concept of labour entitlement to value exists formally in law (labour contracts, minimum wages, social insurance) but is not fully realized through independent unions:

All unions are state-affiliated (ACFTU), limiting collective bargaining outside state frameworks.

Worker participation in surplus distribution is mediated via state policy rather than independent negotiation.

3. Value flow in Chinese system (simplified)

Labour + Capital (state + private) → Production → Revenue

│

├─ Wages → Labour (regulated by policy; some entitlement)

├─ Profit → Private capitalists (market-driven)

├─ State profit → Reinvested / public programs / strategic industries

├─ Rent / Interest → Controlled (banks, debt)

└─ Capital gains → Limited by regulatory controls

Key points:

Profit is not entirely private: a significant portion is claimed by the state and reinvested in productive assets.

Rentier extraction is limited: financial gains are subordinate to industrial and infrastructural development.

Union movement is curtailed, but state acts as a proxy to manage labour claims and maintain stability.

4. Comparison with other systems

5. Key observations

State acts as mediator between labour and capital

Reduces the gap between labour value creation and profit capture compared to Western financial capitalism.

Essentially imposes a quasi-Marxian distribution without eliminating private profit incentives.

Limited rentier class

Unlike the West, asset speculation and interest extraction are tightly regulated.

Household and corporate wealth accumulation occurs, but is not allowed to dominate the economy.

Labour’s entitlement is formalized but constrained

Workers receive a share of production (wages, social benefits), but collective bargaining is channeled through the state.

Independent enforcement of surplus entitlement is minimal.

Hybrid productive-focus

The system prioritizes industrial and technological productivity, echoing the classical or Marxian emphasis on productive investment rather than purely financial gain.

✅ Summary

China’s system:

Resembles classical or Marxian productive capitalism in that labour is tied to tangible production and the state directs surplus toward growth.

Minimizes rentier/financial dominance seen in Western economies.

Labour entitlement exists indirectly via state regulation rather than independent union negotiation.

It is a state-capitalist, hybrid system: productive focus plus limited redistribution, constrained rentier power, and controlled labour claims.

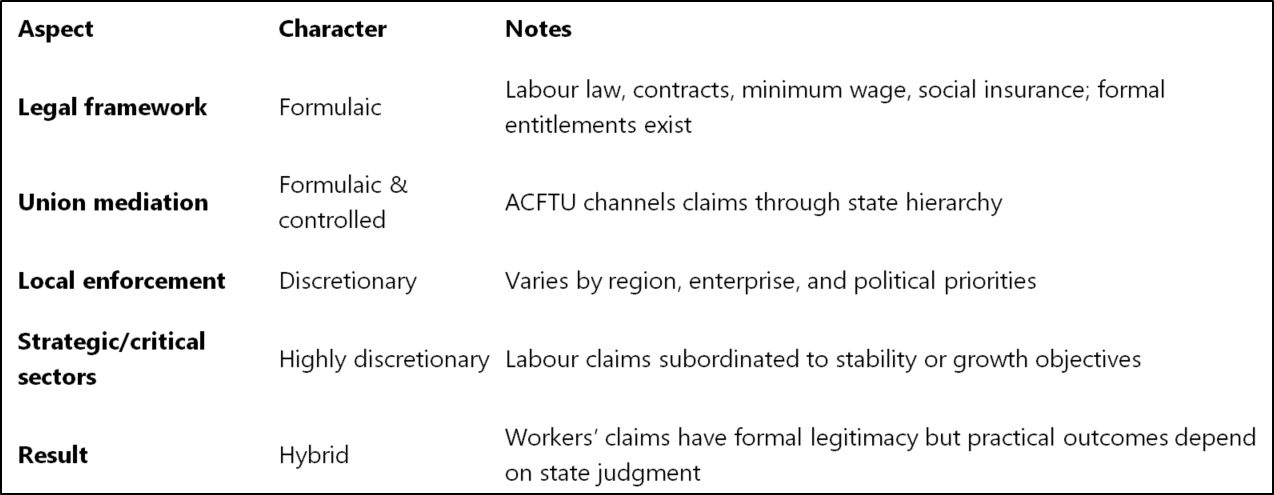

How the Chinese state acts as a proxy to manage labour claims

The Chinese system blends formal rules, policy objectives, and discretionary management. The “state as proxy” does follow a general formula or framework, but there is significant discretion in application, making it seem capricious at times. Let’s break it down carefully.

1. Formal framework: the “formula”

The state manages labour claims via laws, regulations, and policy directives. Core elements include:

Labour laws and contracts

Chinese Labour Law (1994) and Labour Contract Law (2008) set minimum standards: wages, working hours, overtime, termination, social insurance.

Formally, these guarantee workers a legal share of value created, i.e., entitlement to wages, benefits, and protections.

State-controlled unions

All unions are part of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU).

These unions negotiate with employers but under the guidance of the state, not independently.

This creates a formulaic mediation process: disputes go through ACFTU, which is tasked with balancing social stability, productivity, and state objectives.

Policy-driven wage and redistribution mechanisms

Minimum wage adjustments, regional wage guidelines, social insurance contributions, and targeted poverty alleviation programs provide predictable channels for ensuring labour receives a portion of productivity gains.

Enterprises are expected to comply or face administrative penalties.

Enterprise-level grievance mechanisms

Mandatory complaint procedures, internal mediation, and local government oversight ensure a structured process for labour claims.

In short: there is a formulaic legal and bureaucratic framework that governs labour claims. Workers have codified rights; employers have codified obligations; the state is formally the intermediary.

2. Discretion and political mediation: the capricious element

Despite the formal rules, in practice, enforcement is heavily mediated by political and social considerations:

Local variation

Provincial and municipal governments may interpret labour laws differently based on economic priorities, local budgets, or political concerns.

Wage enforcement, overtime compliance, and labour dispute resolution vary widely across regions.

State prioritization of stability and productivity

Labour claims may be suppressed or delayed if the state deems it necessary for social stability or economic growth.

Example: strikes in strategic industries are rarely tolerated; enforcement may be selective.

Employer leverage within state-sanctioned framework

State mediation can favor large or politically connected firms over workers, subtly shaping outcomes.

The system allows negotiated settlements, but the ACFTU often prioritizes continuity of production over maximized labour claims.

Policy discretion in reform periods

During shifts (e.g., privatization of SOEs in the 1990s, labor law revisions in 2008), enforcement is uneven and appears capricious from the worker’s perspective.

3. Summary: formula vs. discretion

In other words: the formula exists, but its application is conditional on political and economic context. The state is not capricious in principle, but outcomes can feel capricious because discretion is built into the system.

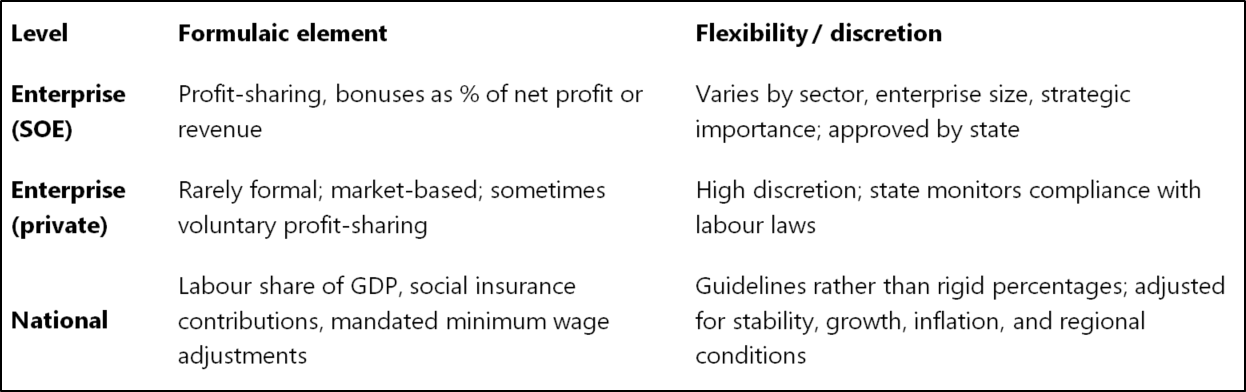

How China sets the value of labour

Ah — now I understand precisely what you mean. You’re asking whether the state mediates labour claims using a fixed quantitative formula, like a percentage of profits or value produced, either at the firm level or national level. The answer is nuanced: in China, there isn’t a rigid, uniform formula, but there are guidelines and frameworks that function in a quasi-formulaic way, applied at multiple levels. Let’s unpack this carefully.

1. Firm-level approaches

State-owned enterprises (SOEs)

Many SOEs operate under state guidelines for wage and bonus distribution, which often link labour compensation to profits or revenue.

Example mechanisms:

Annual performance bonuses may be set as a percentage of enterprise net profit (commonly 5–15% for frontline workers, depending on industry).

Profit-sharing pools exist in some SOEs for employees, usually capped and tiered.

These percentages are negotiated and approved by state authorities, so they are semi-formulaic but flexible: different for heavy industry, utilities, or tech.

Private enterprises

No mandated formula exists. Wages are usually market-determined but guided by minimum wage regulations and local wage benchmarks.

Some firms voluntarily implement profit-sharing schemes, particularly in high-tech and export sectors, but this is not universal.

2. National-level approaches

At the national level, the Chinese state influences labour’s share indirectly:

Labour share of GDP:

Central authorities monitor the aggregate wage share of national income, aiming to maintain social stability.

For example, state documents may recommend that wages grow in line with GDP or productivity, often targeting roughly 50–55% of value-added in certain sectors, but these are guidelines, not enforceable formulas.

Social insurance and redistribution:

National contributions to pensions, healthcare, unemployment insurance, and housing subsidies increase labour’s effective claim on value produced.

These contributions act like an implicit percentage of GDP or enterprise payroll, but vary by sector, region, and firm size.

3. Key distinctions

4. Practical implications

Quasi-formulaic approach:

SOEs are closest to the idea of a “formula”: wages and bonuses tied to profit percentages, often negotiated with state oversight.

Discretion and variability:

The “percentage” is not uniform across all enterprises or sectors.

Private firms often diverge, especially where state oversight is weaker or enforcement is lax.

Macro-level regulation:

The state ensures labour maintains a roughly consistent share of national output, indirectly controlling inequality and social stability.

This is why labour entitlements appear formulaic on a national scale, even if not codified at the individual enterprise level.

✅ Summary

There is no rigid, universal formula for labour entitlement as a fixed percentage of profits or value produced.

SOEs: semi-formulaic, with profit-sharing and bonus pools guided by state policy.

Private firms: largely market-based, with voluntary or guideline-based profit-sharing.

National level: labour share of GDP and social insurance contributions act like a “macro formula” to ensure entitlement, but flexible and policy-driven.

Overall: the system balances formula-like guidance with discretionary, context-dependent application, both at the venture and national scale.

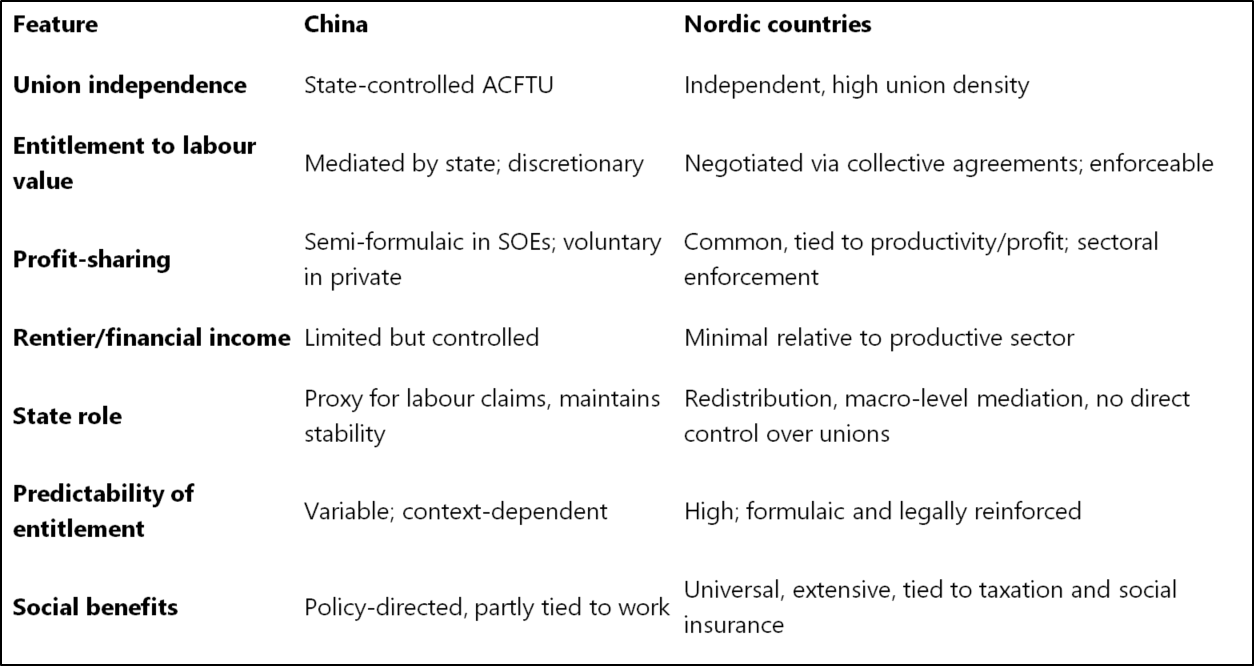

The Nordic countries - mixed capitalism

The Nordic countries — Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, and Iceland — present yet another model for labour entitlement and value distribution, very different from China or financialized capitalism. They combine:

High labour share of value produced,

Strong independent unions and collective bargaining, and

Extensive social redistribution.

Let’s examine the key features.

1. Labour entitlement and collective bargaining

Nordic economies are characterized by high union density (often 60–80% of the workforce).

Collective agreements (tariffavtal or overenskomst) set wages and benefits as a negotiated percentage of value produced or company revenue in many sectors:

For example, wage negotiations in manufacturing often tie pay growth to productivity gains.

Agreements may include profit-sharing clauses or bonuses that directly link labour compensation to profits.

Labour unions are independent of the state, unlike in China, giving workers a direct claim to value produced.

In other words: Nordic workers’ entitlement is formalized, enforceable, and generally negotiated as a percentage of value or productivity, often at the sectoral or enterprise level.

2. State role: mediation and redistribution

The state does not control unions but plays a complementary role through:

Minimum wage laws (though many wages are set via unions)

Social safety nets (pensions, healthcare, unemployment benefits)

Macro-level redistribution via taxation to maintain equity

Labour entitlement is thus enforced both directly through collective bargaining and indirectly via policy-mediated redistribution.

3. Value flows in Nordic systems (simplified)

Labour + Capital → Production → Revenue

│

├─ Wages → Labour (set via collective agreements; often tied to productivity)

├─ Profit → Capital (regulated; moderate)

├─ Taxes → State (for redistribution)

├─ Social benefits → Labour (unemployment, healthcare, pensions)

└─ Rent / Interest → Limited; financial speculation is minor relative to productive investment

Key points:

Workers receive a larger share of productivity than in China or Western financialized capitalism.

Profit remains with capital owners but is moderated by strong regulation and taxation.

Financial rentier income exists but is less dominant, and speculative financialization is much weaker than in the US or UK.

4. Nordic “formula” for labour entitlement

Unlike China, the formula is often explicit and enforceable via collective agreements:

Wages may be negotiated as a percentage of profits, productivity, or sectoral average.

Bonuses and profit-sharing schemes are common and widespread.

At the national level, redistribution and social contributions ensure a fairly uniform entitlement to value across sectors and regions.

This creates a system where labour receives a predictable, enforceable share of value, unlike the discretionary Chinese system or market-determined Western financial capitalism.

5. Comparison table: China vs Nordic countries

✅ Summary

Nordic countries combine formal formulae (collective agreements) with strong redistribution, ensuring labour receives a predictable share of value.

China relies on state mediation, which introduces discretion and variation, though SOEs may implement semi-formulaic profit-sharing.

Western financialized capitalism relies largely on market-determined wages, leaving labour entitlement to value largely unprotected.

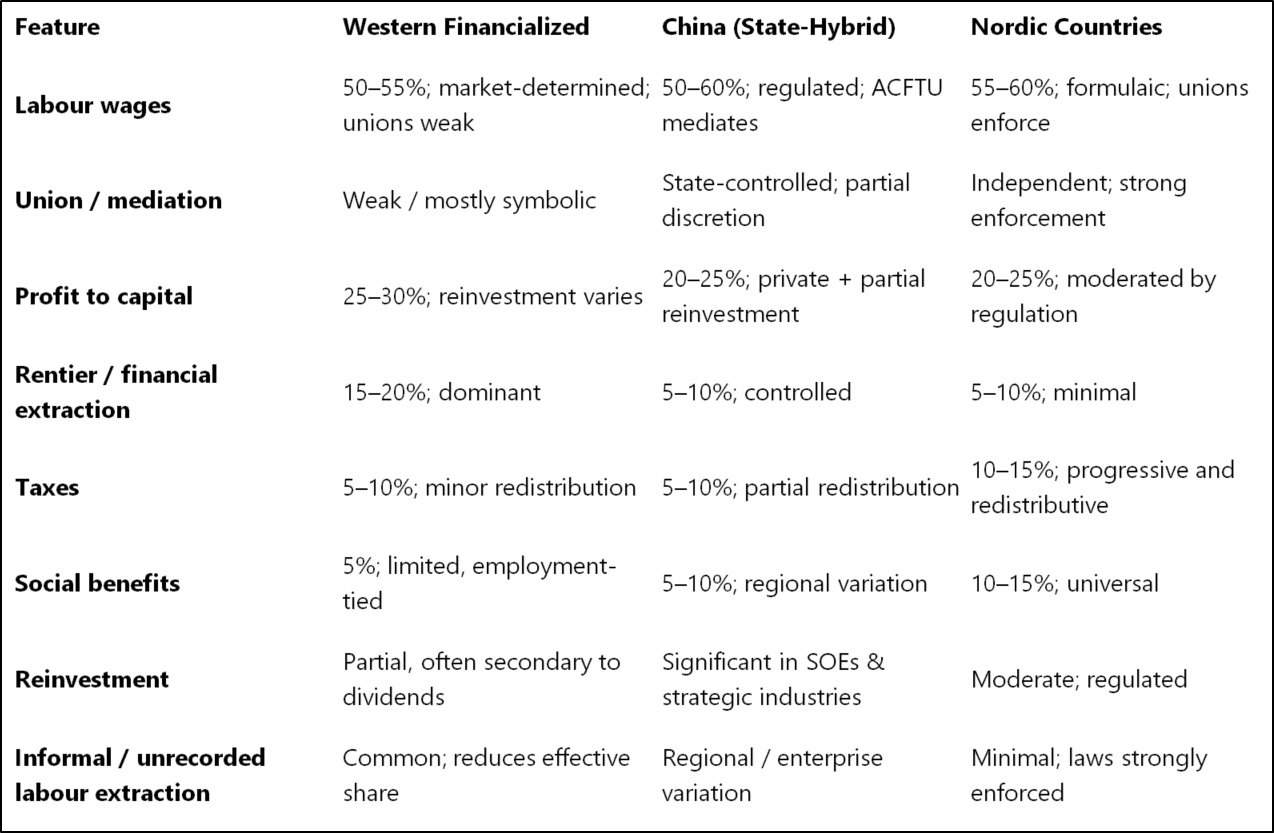

Comparative Diagram: Labour, Capital, and Rentier Flows

Here’s a side-by-side schematic comparison of labour entitlement and value flows in China, Nordic countries, and Western financialized capitalism. I’ve included labour’s share, profit, rentier income, and state/union mediation.

1. Western Financialized Capitalism

---------------------------------------------------

Labour + Capital → Production → Revenue

│

├─ Wages → Labour (market-determined; often stagnant)

├─ Profit → Capitalists / Corporations

├─ Rent / Interest → Rentiers / Financial sector (dominant)

└─ State / Redistribution → Minor; welfare limited

Notes: Labour entitlement is weak; unions weakened; speculative finance dominates.

---------------------------------------------------

2. China (State-Directed / Hybrid Capitalism)

---------------------------------------------------

Labour + Capital (state + private) → Production → Revenue

│

├─ Wages → Labour (regulated; partially tied to productivity)

├─ Profit → Private capitalists (market-driven)

├─ State profit → Reinvestment, strategic industries

├─ Rent / Interest → Controlled (banks, debt)

└─ Social benefits → Labour (insurance, pensions, partial redistribution)

Notes: Labour claims mediated by state (ACFTU); formulaic in SOEs, discretionary elsewhere; rentier extraction limited.

---------------------------------------------------

3. Nordic Countries (Collective / Social Democratic)

---------------------------------------------------

Labour + Capital → Production → Revenue

│

├─ Wages → Labour (collective agreements; tied to productivity/profit)

├─ Profit → Capitalists (regulated, moderate)

├─ Rent / Interest → Minimal

├─ Taxes → State (for redistribution)

└─ Social benefits → Labour (universal, extensive)

Notes: Labour entitlement formulaic and enforceable; unions independent; rentier extraction minimal; state redistributes to ensure equity.

Key Takeaways

Western financialized capitalism

Labour entitlement is weak; wages market-determined.

Rentier and financial incomes dominate; unions relatively weak.

China

Labour entitlement is mediated by the state; partially formulaic in SOEs.

Private profit exists but is subordinated to state strategic objectives.

Rentier income is limited and tightly controlled.

Nordic countries

Labour entitlement is formulaic and enforceable via unions and collective agreements.

Profit is moderated and social redistribution is strong.

Rentier income and speculative finance are minimal relative to productive investment.

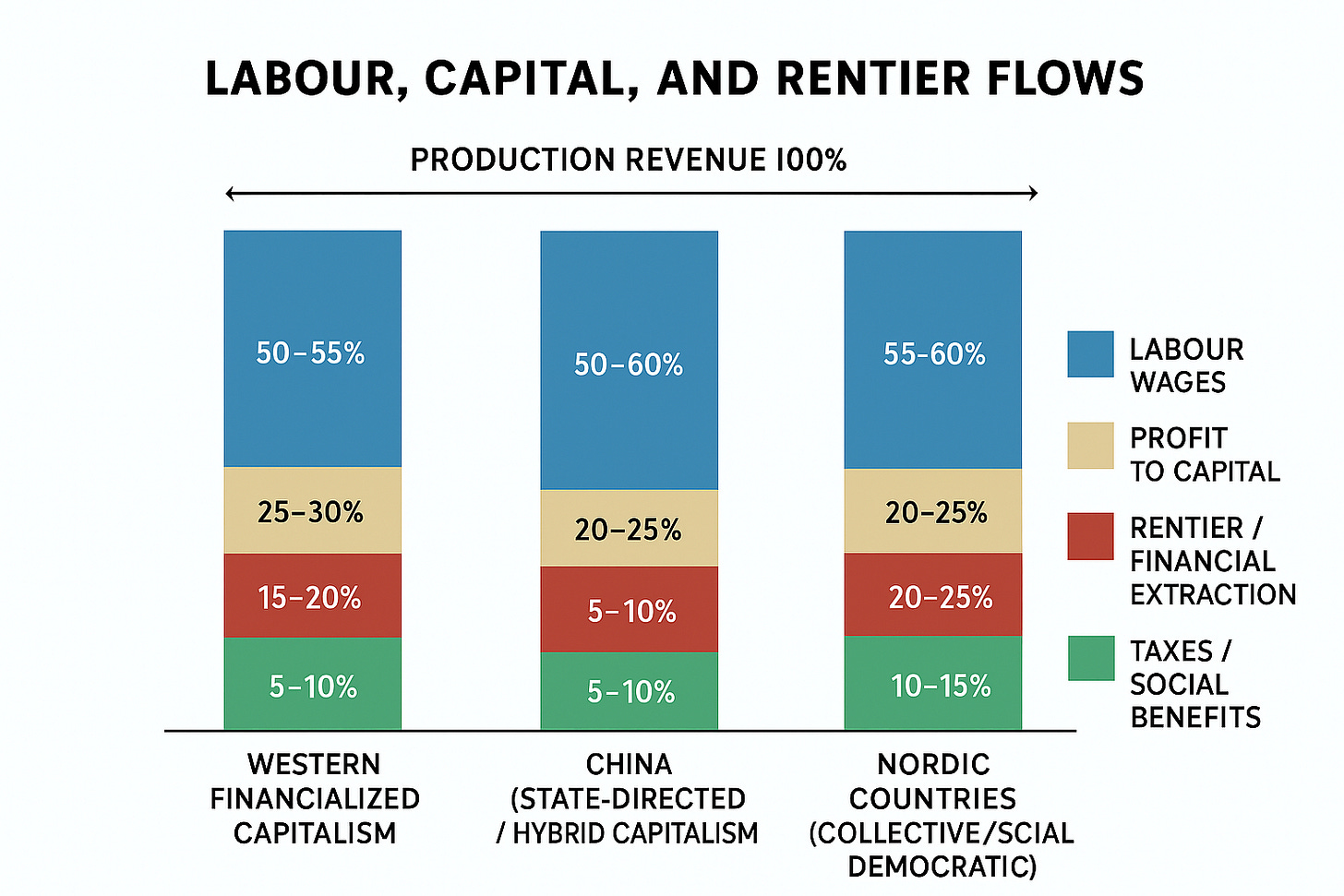

Here’s a visual flowchart-style diagram comparing the three systems. I’ve approximated labour share, capital/profit, and rentier/financial extraction to make the differences immediately clear. Percentages are illustrative, based on typical macroeconomic data and labour share studies.

Labour, Capital, and Rentier Flows: Comparative View

1. Western Financialized Capitalism

---------------------------------------------------

[Production Revenue 100%]

│

├─ Labour wages ≈ 50–55%

├─ Profit to capital ≈ 25–30%

└─ Rent / Interest / Financial returns ≈ 15–25%

Notes: Labour entitlement weak; unions diminished; finance dominates.

---------------------------------------------------

2. China (State-Directed / Hybrid Capitalism)

---------------------------------------------------

[Production Revenue 100%]

│

├─ Labour wages ≈ 50–60% (regulated, partially tied to productivity)

├─ Profit to private capital ≈ 20–25%

├─ State surplus / reinvestment ≈ 15–20%

└─ Rent / interest ≈ 5–10% (controlled)

Notes: Labour claims mediated by state; formulaic in SOEs, discretionary in private sector.

---------------------------------------------------

3. Nordic Countries (Collective / Social Democratic)

---------------------------------------------------

[Production Revenue 100%]

│

├─ Labour wages ≈ 55–60% (formulaic, enforceable via unions)

├─ Profit to capital ≈ 20–25% (moderated by regulation)

├─ Rent / interest ≈ 5–10%

└─ Taxes / social redistribution ≈ 10–15% (universal benefits)

Notes: Labour entitlement strong; unions independent; redistribution ensures equity.

Visual Interpretation

Labour share:

Weakest in Western financialized capitalism.

Moderately strong in China (state-mediated).

Strongest in Nordic countries (union/formulaic).

Profit/capital:

High in Western capitalism.

Moderate in China (private) and Nordic countries.

Rentier/financial extraction:

Dominant in Western capitalism.

Limited and controlled in China.

Minimal in Nordic countries.

Redistribution / state intervention:

Minor in Western capitalism.

Medium in China (via state surplus and social insurance).

High in Nordic countries (progressive taxation, social benefits).

This shows how “labour entitlement to value” varies:

Nordic system: formulaic, enforceable, independent unions

China: semi-formulaic, state-mediated, partially discretionary

Western financialized: weak, market-determined, rentier-dominated

The place of taxes

You’re right — that was an important omission. Taxes do exist in Western financialized capitalism, but I originally left them out because, relative to Nordic or Chinese systems, they play a much smaller redistributive role in terms of labour entitlement. Let me clarify and refine the picture.

1. Taxes in Western financialized capitalism

Western economies (US, UK, etc.) do collect taxes: income tax, payroll taxes, corporate taxes, and social contributions.

However, their effect on labour’s share of production is comparatively minor:

Direct wages may be taxed, but social benefits are often limited (especially in the US).

Corporate profits are taxed, but high deductions and loopholes reduce redistributive impact.

Financial/rentier gains are lightly taxed in some cases, allowing speculation to dominate.

Typical outcome: labour entitlement is largely determined by the market, not by redistribution via tax.

2. Revised breakdown including taxes

For illustrative purposes (approximate macro shares):

1. Western Financialized Capitalism (revised)

---------------------------------------------------

[Production Revenue 100%]

│

├─ Labour wages ≈ 50–55%

├─ Profit to capital ≈ 25–30%

├─ Rent / Interest / Financial returns ≈ 15–20%

└─ Taxes / social redistribution ≈ 5–10%

Notes: Labour entitlement weak; redistribution limited; financial speculation dominates; unions weakened.

Here, taxes exist, but they don’t substantially increase labour’s effective claim to production value compared to Nordic countries.

3. Comparison with Nordic countries

In the Nordic model, taxes and social contributions account for 10–15% of production, funnelled directly back to labour in the form of universal benefits.

In Western systems, taxes exist but largely fund government operations, military, or non-labour social spending — the labour entitlement effect is small.

✅ Key point

Leaving out tax in my earlier diagram was misleading.

Including it emphasizes that Western labour entitlement is only slightly augmented by redistribution, unlike in Nordic countries where taxes and social contributions form a significant part of the labour’s effective share of value.

Other system elements

To make a fully comprehensive comparative diagram, we should consider a few additional elements beyond wages, profits, rentier income, and taxes/social redistribution. Here’s what else might be missing:

1. Labour benefits and social protections

Western financialized capitalism:

Social benefits exist but are often limited (US: employer-provided healthcare, Social Security).

Labour entitlement depends heavily on employment status; informal or gig work is underprotected.

China:

Social insurance (pensions, healthcare, housing) partially supplements wages.

Access varies regionally and between SOEs and private enterprises.

Nordic countries:

Universal benefits (healthcare, pensions, unemployment insurance, education) are extensive.

Labour’s effective share of value is increased by these benefits.

For visual clarity, social benefits could be represented as an extension of labour’s entitlement, separate from wages.

2. Labour-union mediation strength

This affects how entitlements are enforced:

Western: unions weak, so labour claims largely determined by market.

China: state mediates, unions are proxies — formulaic in SOEs, discretionary elsewhere.

Nordic: strong independent unions enforce formulaic, negotiated entitlements.

Could add a “mediation arrow” in the diagram showing the pathway through which labour claims are enforced.

3. Informal or unrecorded extraction / exploitation

Western: gig economy, subcontracting, unpaid overtime — labour’s effective claim may be lower than official wages suggest.

China: rural–urban migration, temporary contracts — similar effect.

Nordic: minimal; strong enforcement of labour laws reduces informal exploitation.

Optional to include in diagram as a “grey zone” reducing labour’s effective share.

4. Capital reinvestment vs personal accumulation

Not all profit goes to private owners: some is reinvested in the firm:

China: significant portion of SOE profits is reinvested in infrastructure, tech, or state initiatives.

Western: private corporations often prioritize shareholder returns; reinvestment varies.

Nordic: moderate reinvestment; profits regulated and taxed.

Could show a separate flow for reinvested capital versus owner take.

✅ Summary of what to include in the full diagram

Labour wages

Profit to capital / owners

Rentier / financial extraction

Taxes and social redistribution

Labour benefits (pensions, healthcare, unemployment)

Union/state mediation / enforcement path

Informal / unrecorded labour extraction (optional)

Capital reinvestment vs personal accumulation

Here’s a fully annotated, proportional-flow comparison of labour, capital, and value distribution across Western financialized capitalism, China, and Nordic countries. I’ve incorporated wages, profit, rentier/financial extraction, taxes, social benefits, enforcement mechanisms, and reinvestment. Percentages are illustrative to show relative magnitudes.

Fully Annotated Comparative Diagram

1. Western Financialized Capitalism

---------------------------------------------------

[Production Revenue 100%]

│

├─ Labour wages ≈ 50–55% (market-determined)

│ │

│ └─ Union mediation weak → entitlement largely unenforced

│

├─ Profit to capital ≈ 25–30% (shareholder returns; partial reinvestment)

│

├─ Rent / Interest / Financial returns ≈ 15–20% (dominant financial sector)

│

├─ Taxes ≈ 5–10% (limited redistribution)

└─ Social benefits ≈ 5% (minor; often tied to employment, not universal)

│

└─ Informal / unrecorded labour extraction: reduces effective labour share

Notes: Labour entitlement weak; speculative finance dominates; redistribution minor.

---------------------------------------------------

2. China (State-Directed / Hybrid Capitalism)

---------------------------------------------------

[Production Revenue 100%]

│

├─ Labour wages ≈ 50–60% (regulated; partially tied to productivity)

│ │

│ └─ Union mediation via ACFTU → formulaic in SOEs, discretionary in private firms

│

├─ Profit to private capital ≈ 20–25% (market-driven; partially reinvested)

├─ State surplus / reinvestment ≈ 15–20% (strategic industries, infrastructure)

├─ Rent / interest ≈ 5–10% (controlled)

├─ Taxes / social redistribution ≈ 5–10% (pensions, healthcare, partial redistribution)

└─ Social benefits ≈ 5–10% (insurance, housing, pensions; partial coverage)

Notes: Labour claims mediated by state; SOEs closer to formulaic; rentier extraction limited; regional variation affects enforcement.

---------------------------------------------------

3. Nordic Countries (Collective / Social Democratic)

---------------------------------------------------

[Production Revenue 100%]

│

├─ Labour wages ≈ 55–60% (formulaic; negotiated via independent unions)

│ │

│ └─ Union enforcement strong → entitlements secure and predictable

│

├─ Profit to capital ≈ 20–25% (regulated; moderate)

├─ Rent / interest ≈ 5–10% (minimal)

├─ Taxes ≈ 10–15% (progressive; redistributed)

└─ Social benefits ≈ 10–15% (universal: healthcare, pensions, unemployment, education)

Notes: Labour entitlement formulaic, legally enforceable; redistribution ensures high effective share of value; rentier influence minimal; speculative finance small.

Visual Summary of Key Contrasts

✅ Key Insights

Labour entitlement:

Weakest in Western financialized economies, semi-formulaic in China, strongest and formulaic in Nordic countries.

Financial/rentier dominance:

Western systems: high and structural

China: limited, controlled

Nordic: minimal

State or union mediation:

Nordic: independent unions enforce entitlement

China: state acts as proxy; partially formulaic in SOEs

Western: weak, leaving labour at market discretion

Social redistribution:

Nordic countries provide the largest boost to labour’s effective share through taxes and universal benefits.

How the tax percentages were estimated, because they are illustrative aggregates, not precise values for every enterprise or household. I’ll break it down carefully.

1. Basis for tax percentages

The percentages in the previous diagram represent the portion of total production revenue (GDP) captured as taxes and social contributions, as they affect labour entitlement.

Western financialized capitalism (5–10%)

Taken as an average across major Western economies, e.g., US, UK, and Australia:

Payroll taxes (Social Security, Medicare in the US) ≈ 7–15% of wages

Corporate taxes ≈ 10–20% of profits, but effective rates often lower due to deductions

Consumption taxes / VAT do not directly increase labour entitlement

Combined, the redistributive impact on labour entitlement is limited, so we approximate 5–10% of total production revenue going back to labour via government.

China (5–10%)

Includes:

Social insurance contributions (pension, healthcare, housing) from both employer and employee ≈ 10–12% of payroll on average

Taxes on corporate profits used for infrastructure, education, and some social programs ≈ 3–5% of enterprise revenue

Applied across the national economy, this roughly corresponds to 5–10% of total production revenue flowing to labour via policy-directed redistribution.

Regional and enterprise variation explains the range.

Nordic countries (10–15%)

Progressive income taxes, social security contributions, and employer contributions are high:

Total tax + social contribution rates can reach 30–40% of wages

Corporations pay 20–25% tax on profits, part of which is redistributed through universal benefits

When averaged across the economy and considering the share that benefits labour directly (universal healthcare, pensions, unemployment benefits), we approximate 10–15% of production revenue effectively increasing labour’s entitlement.

2. Notes on methodology

Focus on labour entitlement:

The percentages do not reflect total government revenue, only the part that effectively boosts labour’s share of value created.

Illustrative, macro-level:

Percentages are rounded averages, intended for comparative visual clarity, not precise fiscal accounting.

Individual enterprises, households, or regions may experience higher or lower effective redistribution.

Components included:

Payroll taxes and social insurance contributions

Government spending on benefits (pensions, unemployment, healthcare)

Excluded: general government operations unrelated to labour entitlement (military, debt service, etc.)

Here is a stacked-bar visual provided by ChatGPT, ***I suspect this bar is incorrect***

with each bar showing:

Labour wages

Profit to capital

Rentier/financial extraction

Taxes and social benefits

How the word “interest” came to be used for rental of money

The use of interest to mean “rental of money” has a long and revealing linguistic and moral history.

1. Original meaning

The word interest comes from the Latin interesse, meaning “to be between” or “to matter to someone.” In late Roman and medieval Latin, interesse came to mean compensation for loss — literally, the amount “in between” what should have been and what was received.

For example, if someone failed to deliver goods or repay a loan on time, the injured party could claim interesse — compensation for the delay or damage suffered. This wasn’t yet “profit,” but rather indemnity.

2. Transition to finance

By the 13th–15th centuries, canon law in Christian Europe still prohibited usury — any profit made from lending money — as morally wrong. However, merchants and bankers needed a way to justify compensation for the loss of opportunity when money was lent.

They began calling this compensation interesse (in Italian) or interest (in Middle English, from Old French interest), emphasizing that it was not immoral profit but a kind of damages for the lender’s loss of use.

So originally:

Usury = sinful gain on a loan.

Interest = legitimate compensation for loss.

Over time, especially after the Reformation and the rise of capitalist economies, this moral distinction faded. By the 17th century, interest had become the normal term for the charge on money lent, and usury had narrowed to mean excessive interest.

3. Earlier words

Before interest became accepted, earlier or parallel terms included:

Usura / usury (Latin, Old French, English): literally “use” — the original word for lending profit, later condemned by the Church.

Damnum emergens (“emerging loss”) and lucrum cessans (“ceasing profit”): scholastic legal phrases used by medieval theologians to justify limited compensation on moral grounds.

Rent, gage, or hire were sometimes metaphorically extended to money in early vernacular texts but were not standard.

4. Summary of the shift

Latin interesse → compensation for damage or loss.

Late medieval commerce → allowed lenders to claim interest for lost opportunity.

Reformation and secularization → made interest a neutral term, replacing usury as the everyday word for payment on loans.

Conclusion/TLDR

The modern world’s economic system is based on concepts which arose out of exploitation and the law of the jungle, formulated by those in power in order to retain and enlarge their power. It is not designed to work and does not work in a planned political structure of democracy and human rights.

x

Wow, this article is so timely. It's fascinating how capitalism 'came full circle' – is the modern rental different from feudalisms, or just rebranded?