Selling New Zealand - The Four Lane Highway Debacle, Here Are The Numbers We Are Not Being Told!!! | Knowledge is Power

Here's most of the information needed to make a decision about the wisdom of the National/Act/NZ First coalition to commit its citizens to 10% of our infrastructure expenditure for the next 25 years.

Here's most of the information needed to make a decision about the wisdom of the National/Act/NZ First coalition to commit its citizens to 10% of our infrastructure expenditure for the next 25 years.

** Note: the tables are graphics, so cannot be read out in audio file.

Update

2025-11-04 here’s some real figures from Radio New Zealand

Contents

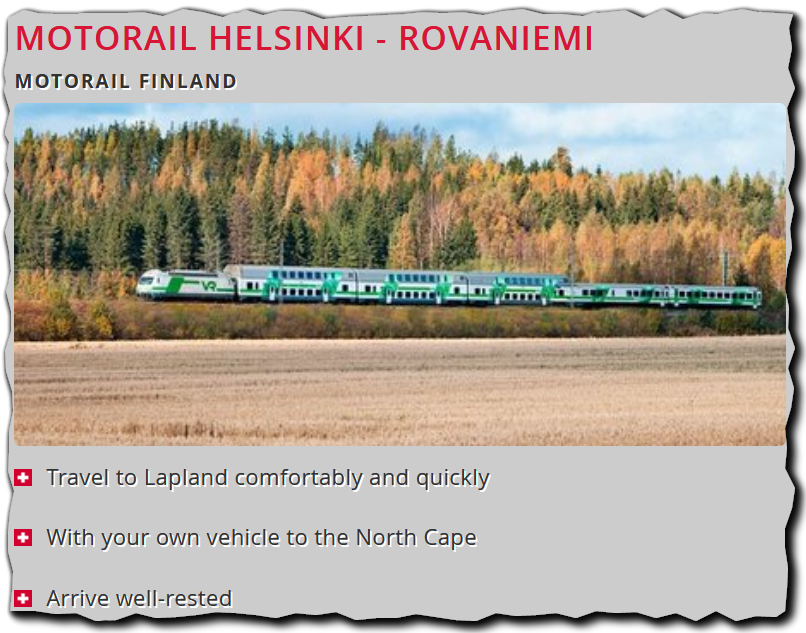

I have always loved trains.

Every time I see one gliding over the overbridge with beautifully stacked logs, or I stop at the bells and lights to see a passenger train passing through, I resist the impule to wave. I fall in love again. Travelling through the mountains, across rivers, through the backs of cities, forests and farms with that quiet rhythm of the tracks passing underneath. The peace of knowing that as you’re watching the ever changing scenery, the changing light of the day or night, you’re calmly and safely being conveyed to your destination.

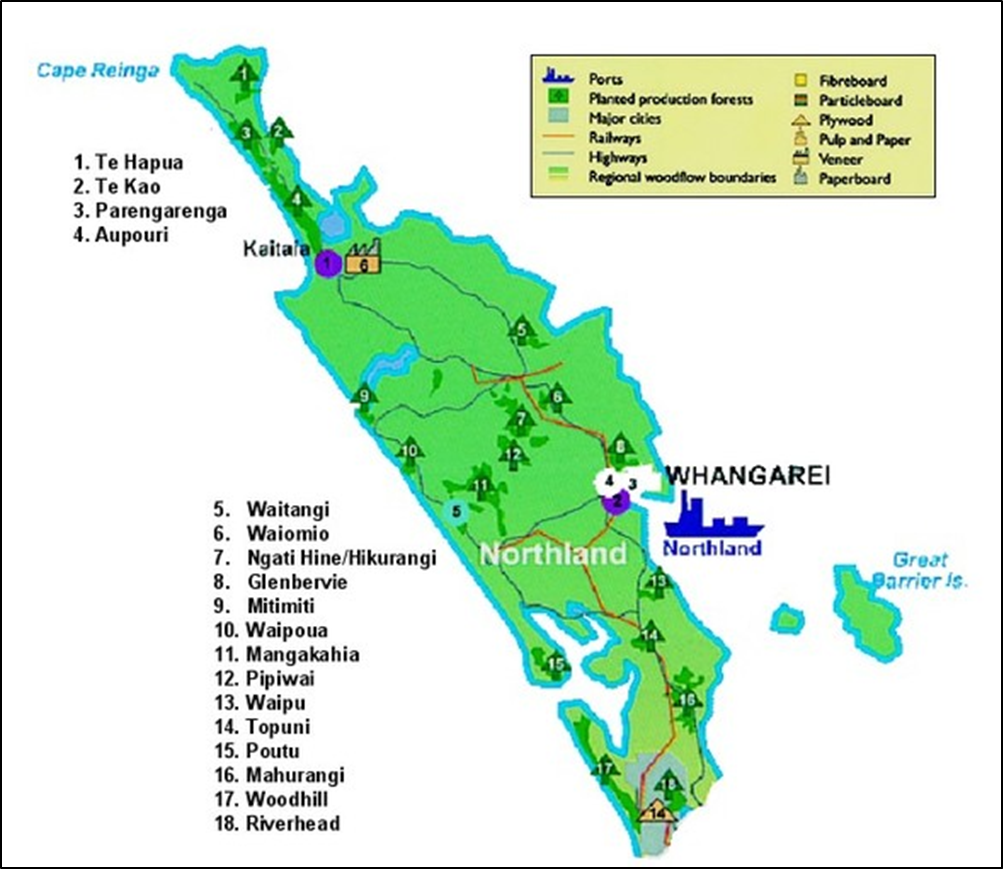

And Northland, with its many beauties including Bay of Islands, Russell, Paihia, Cape Reinga, Ninety Mile Beach, Spirits Bay, and Waipoua Forest — 10% of the geographical area of New Zealand’s North Island — has little, bus-only access by public transport for passengers, and almost all freight is carried by road — wrecking the roads and causing massive ongoing costs.

As soon as someone came up years ago with the idea of repairing our broken train service to our far north, I immediately wanted to see a train that I could drive on in my car, relax instead of that tiring drive, enjoy the scenery and some refreshment, and drive off at the other end - refreshed.

It was so obvious. The trains could open up the north, and transport goods, saving the constant congestion and potholing of roads I see everywhere I go.

But then, nobody implemented it.

That’s why I was utterly appalled by this excellent interview of Chris Bishop by Jack Tame.

The tax deductions to the rich and landlords (instead of home buyers), the undermining of our electoral system are terrible. The almost malicious destruction of jobs, can be rectified in a couple of years.

But the unbelieveable sellout of 10% of our country’s infrastructure expenditure for 25 years, for what will be an ongoing expensive bleeding sore, of cost, pollution and inaccessibility, is not.

So. I spent a couple of hours ascertaining the facts that OUR MEDIA and OUR GOVERNMENT have HIDDEN from us.

From an independent, overseas authority!

I asked ChatGPT: what is the cost and benefit between building the road to Northland proposed by the current NZ govt, compared to building a railway which can transport people who can't afford cars, people with their cars, and freight?

And here they are. A microcosm of what is happening worldwide.

TLDR

🚆 Northland’s Future on Track? Why Rail Would Outperform a $6 Billion Highway

The Government’s proposal to build a four-lane highway between Auckland and Whangārei has reignited a classic question in New Zealand’s infrastructure policy: do we want more roads, or better connections?

The case for upgrading the existing North Auckland Line — the region’s long-neglected railway — offers a surprisingly strong alternative.

When the full costs and benefits are compared, the road looks like a 20th-century solution to a 21st-century challenge. Upgrading the existing North Auckland Line (rail) and maintaining the current highway looks like substantially cheaper — as well as the smarter, fairer, and more climate-aligned choice.

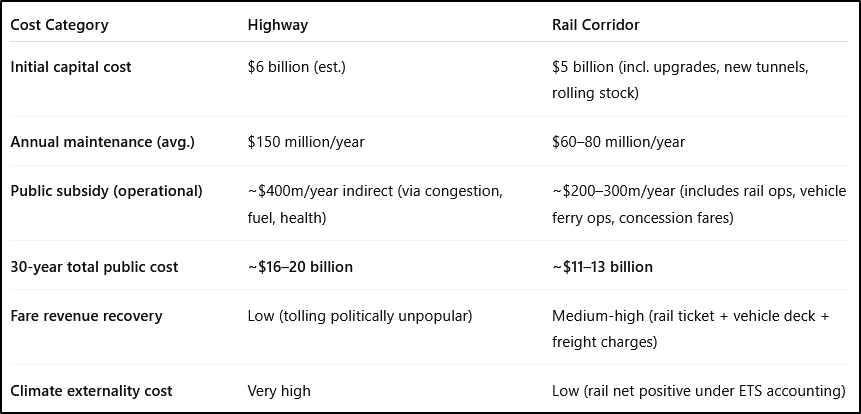

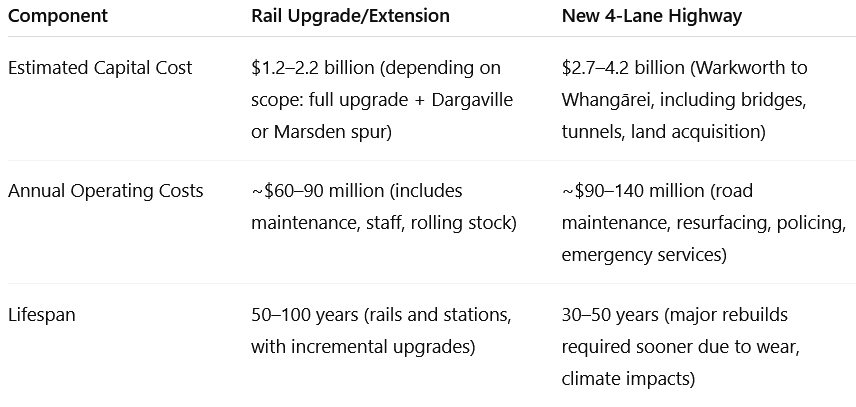

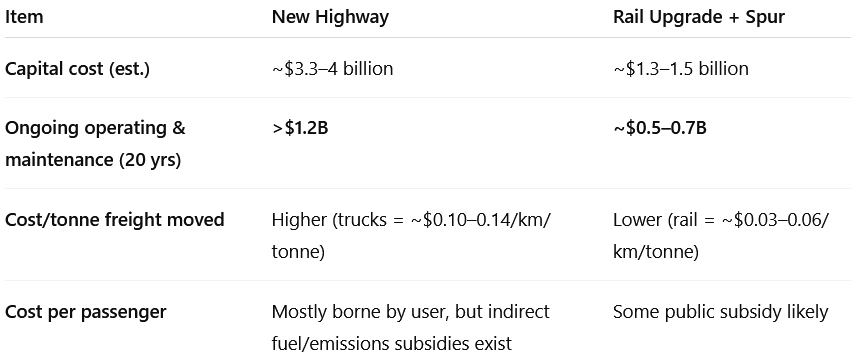

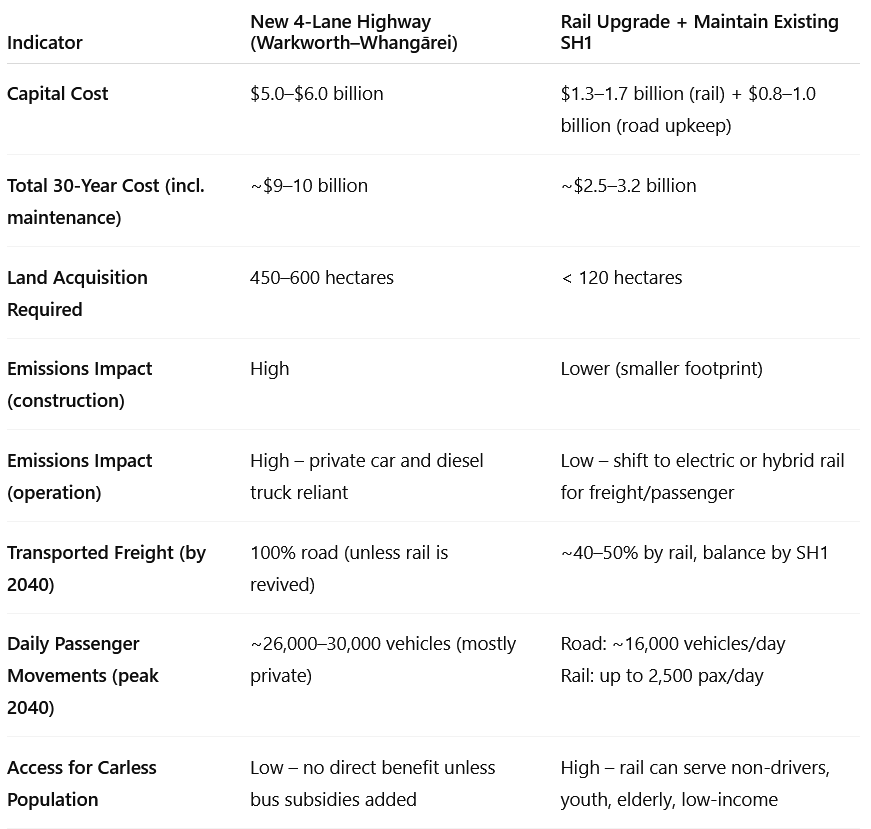

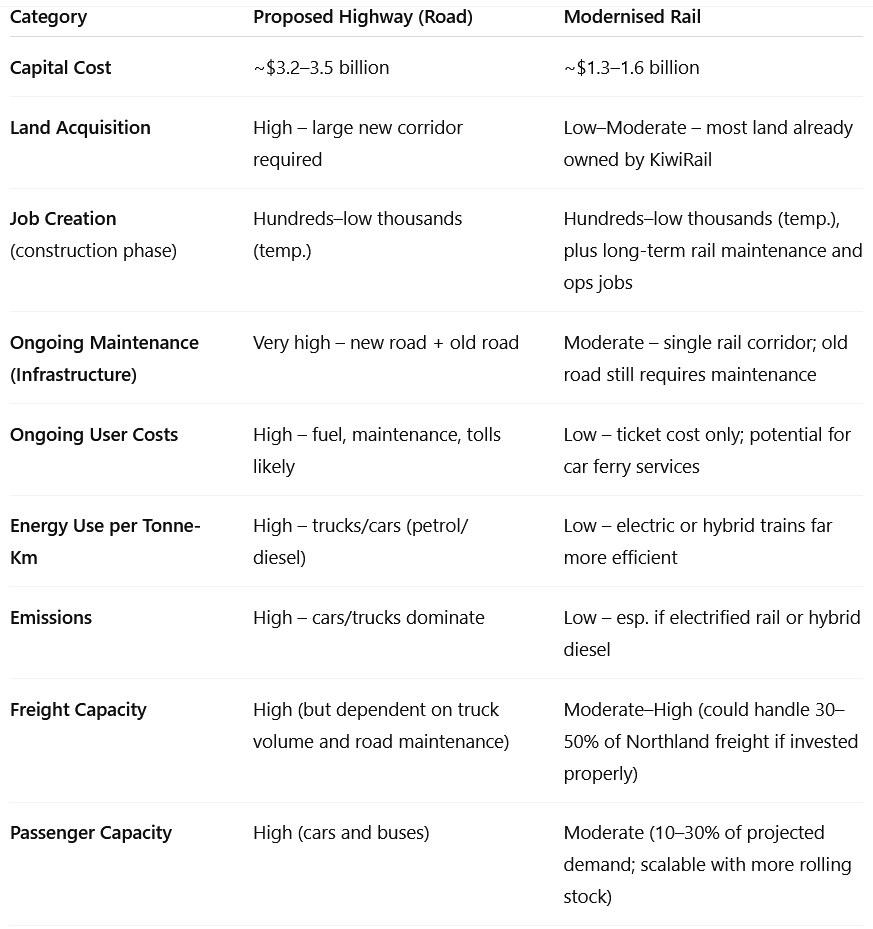

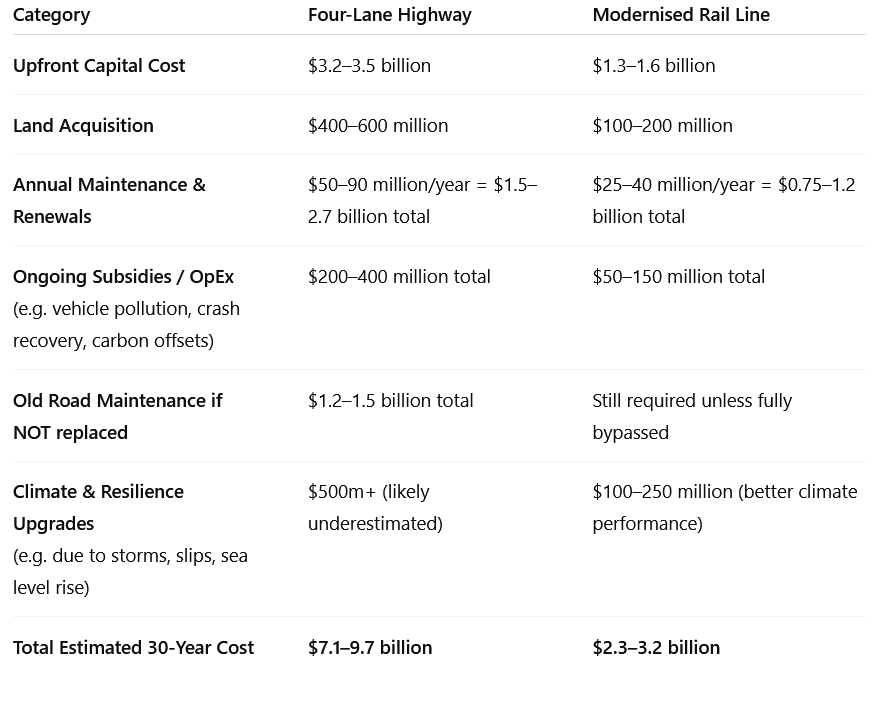

The Price Tag: Four-Lane Highway (Warkworth → Whangārei) Three Times the Cost of Rail

Even allowing for contingencies, the road costs around three times as much as the rail option once ongoing maintenance, climate adaptation, and subsidies are counted.

Rail benefits from using an existing corridor largely owned by KiwiRail, keeping land costs low. The rail + upkeep path is substantially cheaper over 30 years and uses far less new land.

Freight and passenger potential

Northland currently moves ~18 million tonnes of freight per year. Trucks carry almost all of it — ~97–99% — because the railway is slow, single-track, and unelectrified.

With targeted investment, rail could take 40–50% of freight, especially bulk goods (logs, dairy, aggregates, containers).

Passenger rail could serve 10–30% of corridor demand with a reliable timetable and good station connections — crucially serving people who do not own cars and offering an affordable alternative for non-drivers and commuters priced out of Auckland.

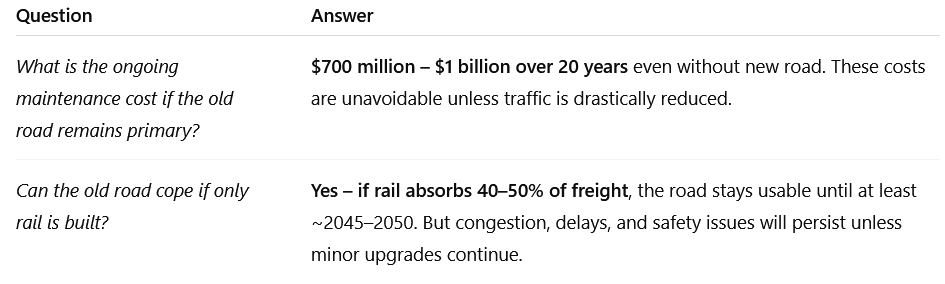

What if We Keep the Old Road?

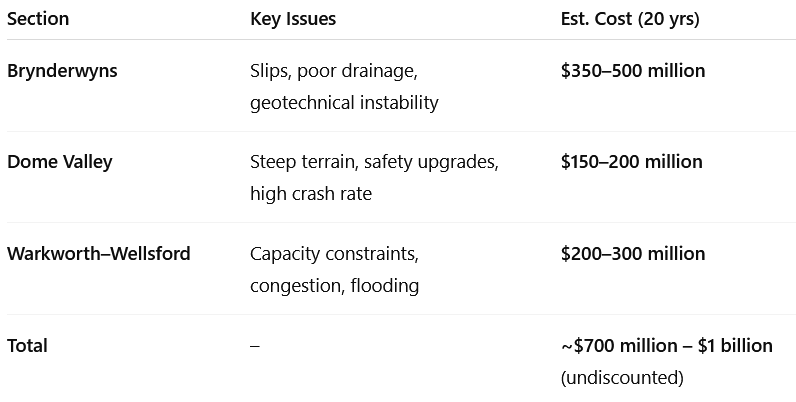

The existing SH1 (Brynderwyns, Dome Valley, Warkworth–Wellsford) will still require maintenance. Estimated $700 million–$1 billion over 20 years for slip management, safety upgrades and resurfacing.

But if half the heavy freight moves to rail, road congestion and wear would drop sharply, extending the life of SH1 for another 15 years without major reconstruction — extending SH1’s usable life and saving public money.

User costs, energy and emissions

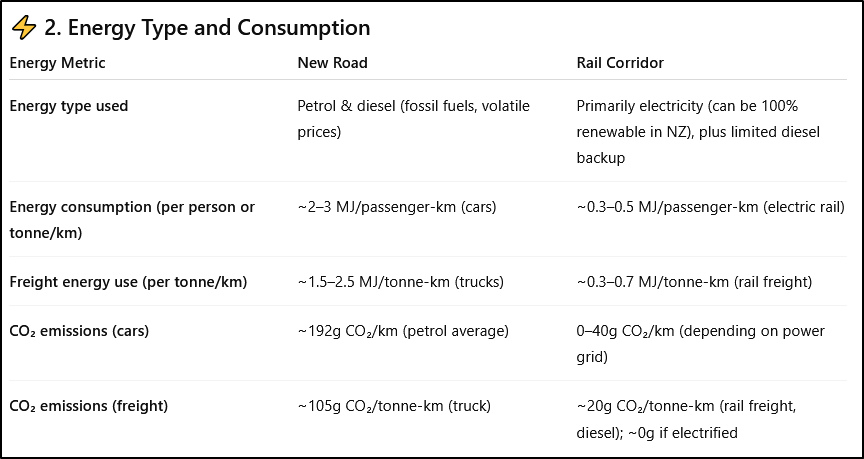

Rail remains roughly three to five times more energy-efficient per tonne-kilometre. In New Zealand, where a large share of electricity is renewable, electrified rail offers substantial decarbonisation potential.

Economic, social and resilience impacts

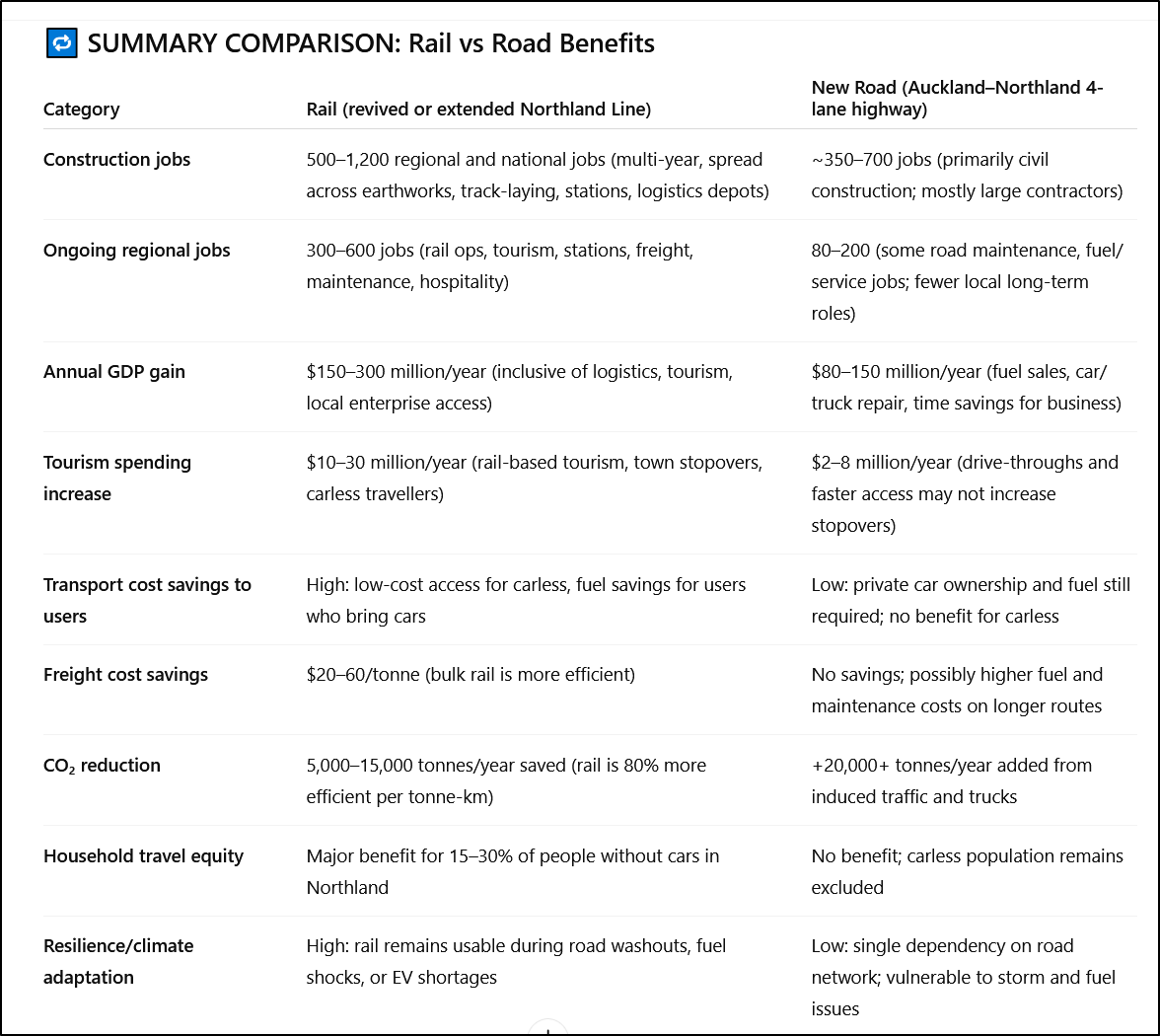

Jobs: Both options create construction jobs; rail creates more ongoing regional jobs (operations, maintenance, tourism, stations).

Tourism: Rail creates station-based tourism and longer stopovers; roads mainly enable drive-throughs and less local spend.

Access: Rail provides affordable access to non-drivers (youth, elderly, low-income), improving equity and labour mobility.

Resilience: Rail offers redundancy when roads close due to slips, floods or fuel supply issues. A rail + maintained SH1 system is far more resilient than a single new motorway.

Environment: New highways cut wide corridors through habitat; rail mostly reuses existing easements and has a smaller footprint.

Rail spreads benefits more evenly. Stations in Whangārei, Ruakākā, Wellsford and Helensville would create local hubs for small business, housing and tourism.

The motorway, by contrast, would mostly benefit construction firms, freight hauliers, and petrol suppliers.

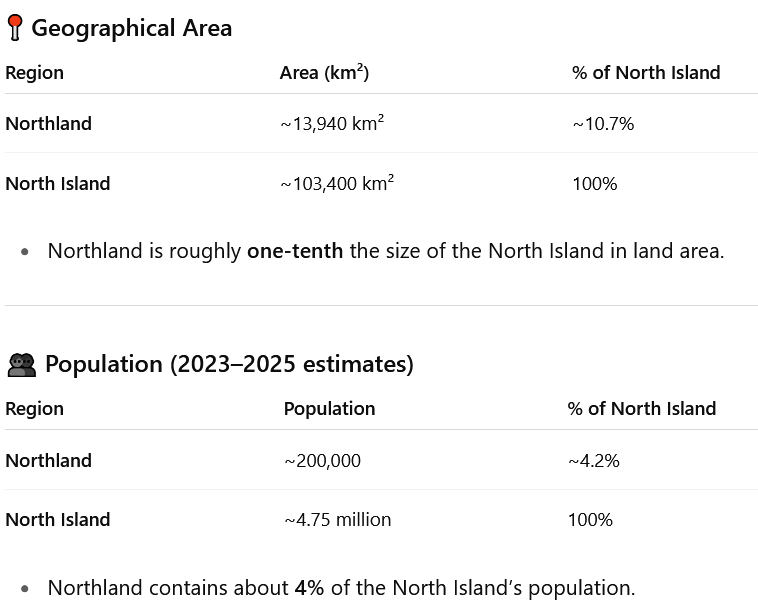

Northland in Context

Area: ~13 940 km² (≈ 10 % of North Island)

Population: ~200 000 (≈ 4 % of North Island)

Density: ~14 people/km² (vs ~46 for the North Island)

With low density and high car dependency, Northland’s residents pay more per capita for transport than urban New Zealanders. A reliable rail link could dramatically lower household and business costs.

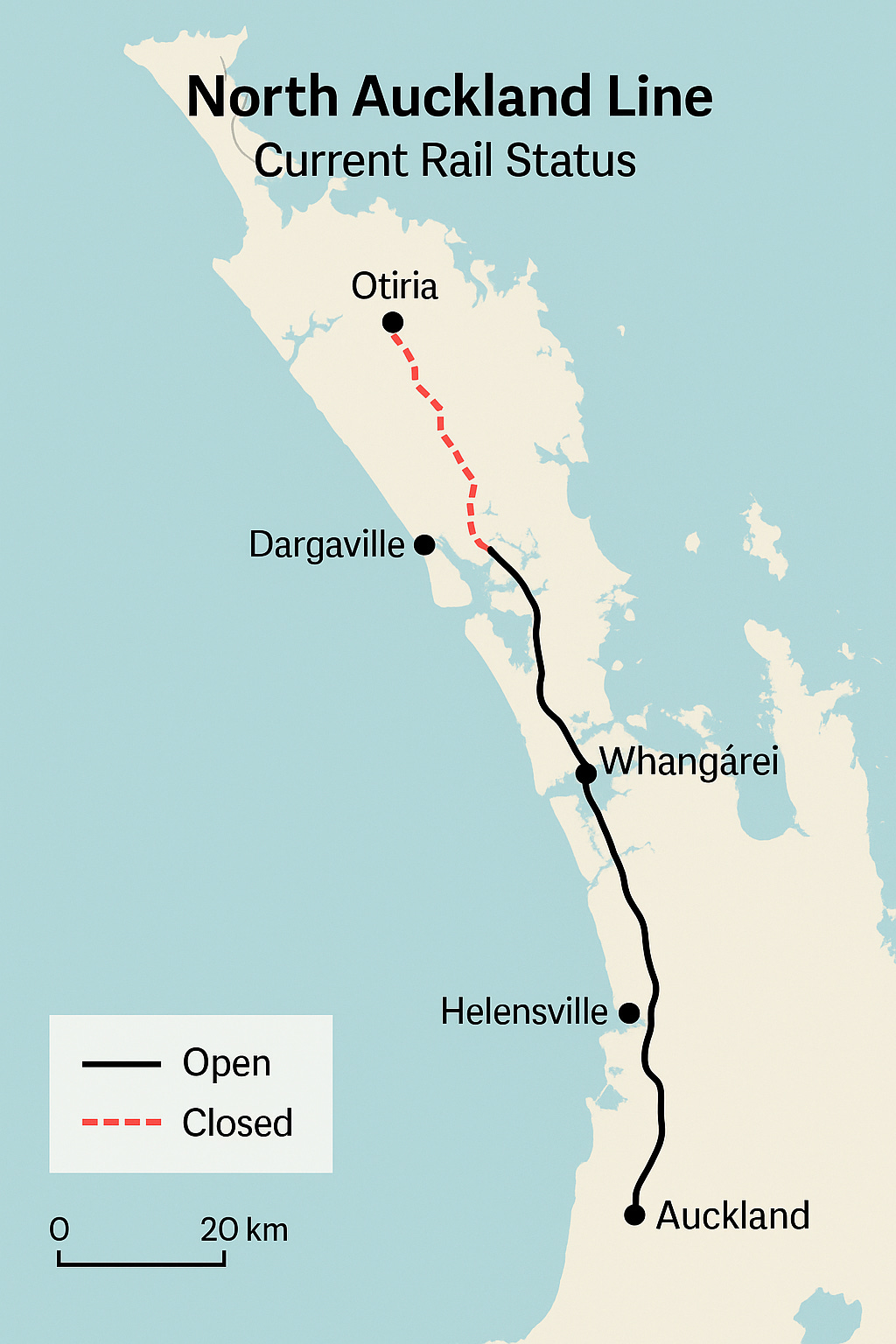

The Present Rail Situation

The North Auckland Line, running from Swanson to Whangārei, is single-track and unelectrified. Speeds can drop below 50 km/h on aging sections.

However, KiwiRail’s current programme of bridge, tunnel, and drainage upgrades has already reopened sections once slated for closure. With targeted investment, the line could support modern regional passenger and high-volume freight within five years.

The Verdict

The motorway delivers faster car trips for those who already drive but is far more expensive, increases fossil-fuel dependence, and concentrates benefits among vehicle owners and heavy hauliers. It is far more carbon-intensive and fragile in a changing climate. It increases New Zealand’s foreign debt due to dependence on retail imported fossil fuels (since the Marsden Point Refinery was gutted, we do not even have a refinery), and purchases and maintenance of trucking and private vehicles. It increases household debt due to higher goods transport cost, and the need for vehicles.

The rail + SH1 maintenance option is cheaper, more inclusive, better aligned with climate goals, and spreads economic benefits into towns along the line, and goods consumers, while taking thousands of trucks off SH1.

For fiscal prudence, social equity, and climate resilience, the evidence supports modernising rail while maintaining the existing highway rather than building a new $3–4 billion motorway. A dual strategy — upgrading rail while maintaining SH1 — would save billions, cut emissions, and strengthen the Northland economy.

🟢 In Short

The highway builds mobility for those who already have it.

The railway builds access for those who don’t.

And in the long run, access is the greater engine of growth.

Quick policy recommendations

Stage rail upgrades: prioritise freight capacity (passing loops, heavier bridges) and a basic, frequent passenger service.

Fund SH1 resilience works: targeted slip remediation, passing bays, and safety improvements — not a full new corridor.

Design for modal integration: park-and-ride, local shuttle services, and freight terminals at Whangārei and Marsden Point.

Price signals: use freight pricing, low-emission incentives, and fares that encourage rail freight and passenger uptake.

Co-fund with private sector: ports, forestry companies, and tourism operators can co-invest in terminals and rolling stock.

Notes & assumptions

Figures are conservative estimates (2025 NZD). They draw on infrastructure cost norms, KiwiRail condition reports, and regional freight/transport models; they are estimates, not official tender figures.

“Total 30-year cost” includes capital, maintenance, expected subsidies or external cost burdens (climate/resilience), and an allowance for inflation and contingencies.

Passenger and freight uptake forecasts assume reasonable service quality, integrated last-mile links, and some policy support (pricing, scheduling).

THE FULL WORKINGS

Current arrangements

A large part of Northlan’d minimal industry is forestry. The forests appear to be well located to be intercepted by the rail line at key locations. The key exceptions would be about 5 forests that are closest to Marsden Point itself.

We already have a highway to the North. Yet the roads are constantly torn up by massive logging, and other freight haulage trucks. Leaving commuters and freight companies with potholes and traffic jams.

Four key rail transfer stations could be established at the following locations for logs to be loaded from trucks onto trains.

Otiria (north end of rail line near Kawakawa)

Dargaville

Wellsford

Helensville

At least 3 of these locations were operating until the last couple of years. Some investment would be required at each of the sites to create a flat yard with space for trucks & log loaders to operate, however, the overall investment would be minimal. (Thanks to The Marsden Point Rail Link - Greater Auckland)

📦 What percentage of Auckland–Northland return freight is currently carried by rail?

As of the most recent data (2023–2024 estimates):

🚂 Rail carries only about 1–3% of the total Auckland–Northland freight task (by tonnage).

📉 Why so low?

The North Auckland Line (NAL) is:

Single-track, non-electrified, with tight curves and steep grades

Freight-only north of Swanson, with no passenger services

Limited to low speeds (30–50 km/h) on some sections

Until 2020, parts of the line were at risk of closure due to deterioration.

Most freight operators (e.g., for logs, produce, fuel, manufactured goods) have long preferred road for speed, flexibility, and capacity.

🚛 Road dominance:

Over 95% of freight between Auckland and Northland is currently moved by trucks via SH1.

Approximately 18 million tonnes of freight moves within and into/out of Northland each year — and less than 0.5 million tonnes is on rail.

Marsden Point – http://marsdenmaritime.co.nz Marsden Point port was opened around the year 2000 to replace the Whangarei Port which was very constrained. Rail was used to transport logs from around Northland to the old Whangarei location, however when the port moved no rail line was built and the traffic was lost. This was a big hit to rail in Northland, with tonnages per annum dropping from 1,000,000 to only 300,000 tonnes.

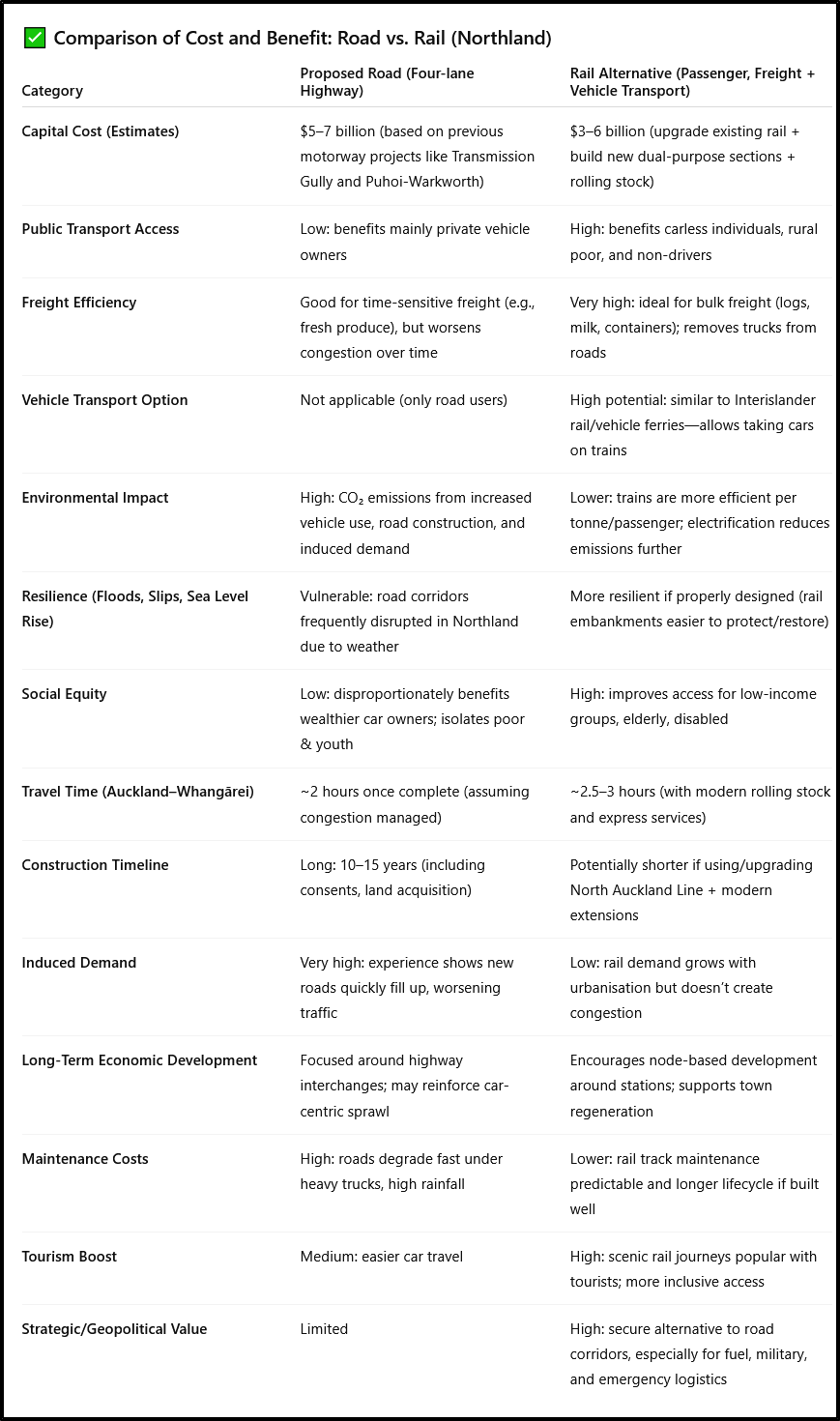

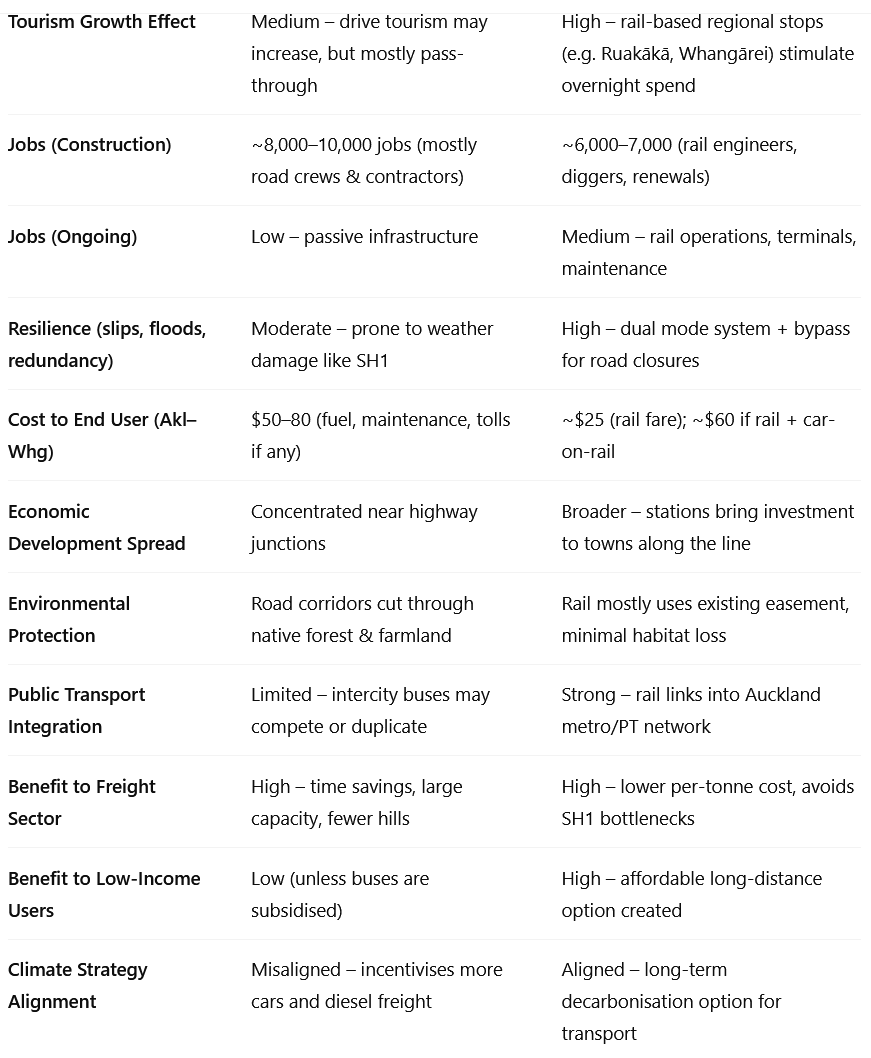

Quick comparison of cost and benefit - Road or Rail?

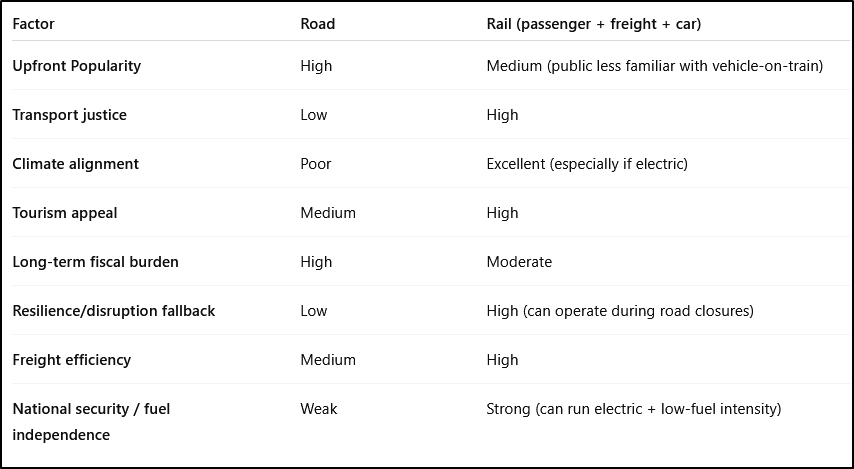

The proposed new road to Northland (sometimes referred to as the four-lane highway from Whangārei to Auckland), promoted by the current New Zealand government, has sparked significant debate. Comparing it to a railway alternative (designed to carry both passengers—including those without cars—and freight, as well as vehicles) involves multiple economic, social, environmental, and long-term resilience factors.

🔄 Examples for Context

Kaikōura Earthquake (2016): Rail line was restored faster than coastal highway, proving its strategic value.

Swiss and Austrian Alps: Rail + vehicle transport is common through tunnels where terrain is hard or preservation is needed.

Norway and Sweden: Remote regions are served by mixed-use rail, helping economic equality.

⚖️ Conclusion:

If the goal is inclusive access, climate resilience, regional development, and long-term freight sustainability, then rail offers better overall public value—particularly when designed to carry passengers, freight, and vehicles.

The road alternative is more politically popular in car-centric cultures - people want their car at their destination, but economically and environmentally more costly in the long run, particularly given New Zealand's climate goals, rising fuel costs, and inequity in transport access.

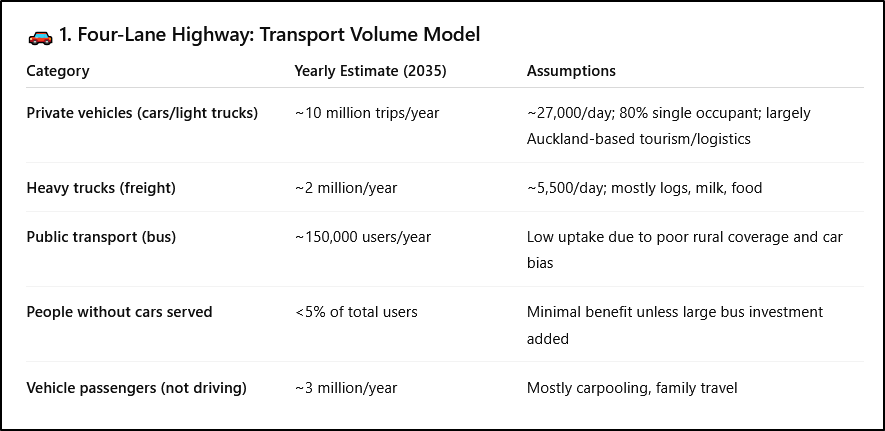

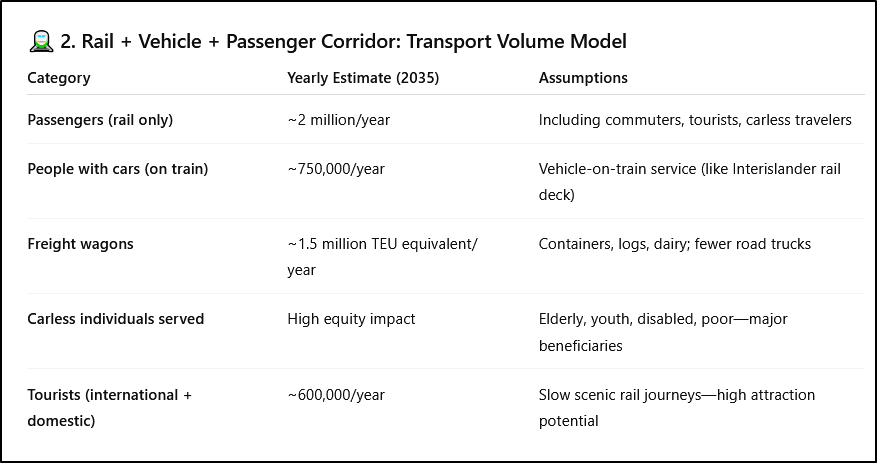

📊 Scenario Model: Northland Road vs. Rail (People, Freight, Vehicles)

Here’s a tailored comparative scenario model for the Northland Road vs. Rail project, showing:

Transport volume assumptions (people, freight, vehicles)

Public subsidy implications over a 30-year horizon

We will model both transport corridors using conservative but realistic figures, based on Northland's demographics, economic freight base (logs, dairy, tourism), and comparison to NZTA [New Zealand Transport Agency] and Kiwirail [National Rail Operator] data.

⚠️ Risks:

Induced demand: likely to increase traffic beyond projections within 10 years.

Carbon emissions: ~400,000+ tonnes CO₂/year (NZTA road GHG data).

Upgrades/repairs: Climate vulnerability may inflate long-term costs.

✅ Benefits:

Carbon emissions reduced: electrified or hybrid rail = ~80% reduction per tonne/km.

Economic development: rail hubs catalyse town regeneration.

Resilience: alternative to roads when blocked (slips, floods).

💰 Public Subsidy + Long-Term Cost Comparison (30-Year Horizon)

🧾 Summary of Strategic Value and Trade-offs

🧭 Final Assessment:

If NZ wants to reduce inequality, improve resilience, and cut emissions, the railway is superior.

If the goal is to maximise car convenience for current drivers, the road is superficially more popular, but far more expensive long term, both fiscally and environmentally.

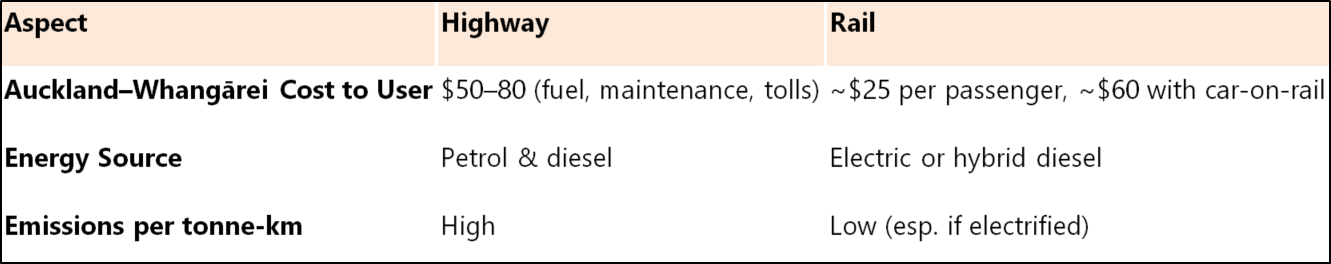

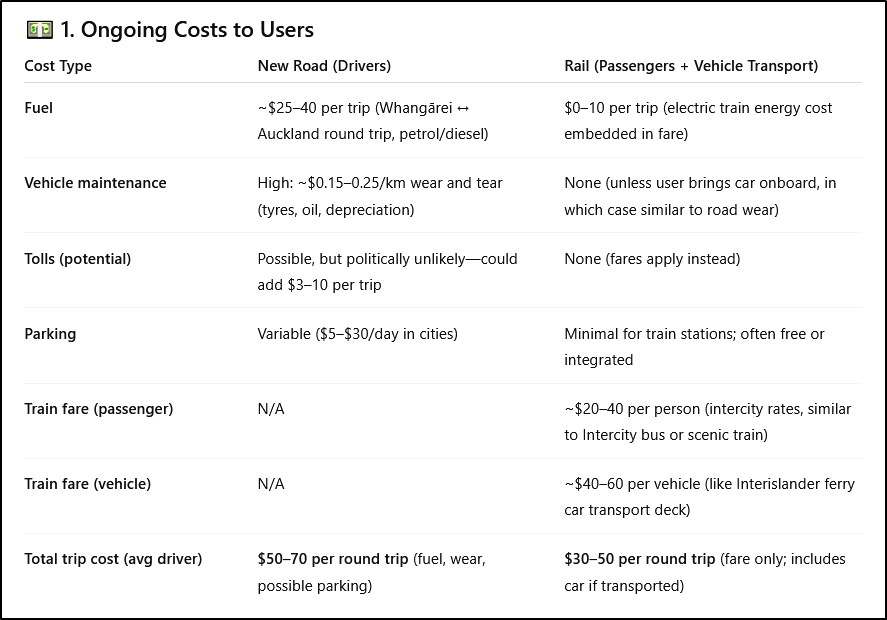

Road vs Rail comparison: cost and energy consumption

Here’s a comparative breakdown of:

Ongoing costs to users (fares, fuel, tolls, vehicle wear)

Energy type and consumption (fuel vs electricity, emissions, efficiency)

This adds to the previous information by considering the personal economic burden, system energy use, and climate impact per user.

💵 1. Ongoing Costs to Users

⚠️ Equity Gap:

Poorer residents without cars pay zero if on road (because they can't use it). With rail, they gain access for a modest fare.

Car ownership costs ~$9,000–11,000/year in NZ; rail avoids this burden.

⚡ 2. Energy Type and Consumption

✅ NZ Advantage:

NZ already produces over 80% of electricity renewably (hydro, wind, geothermal).

Rail can become 100% zero-emission, especially with solar-powered stations + battery-electric or electrified lines.

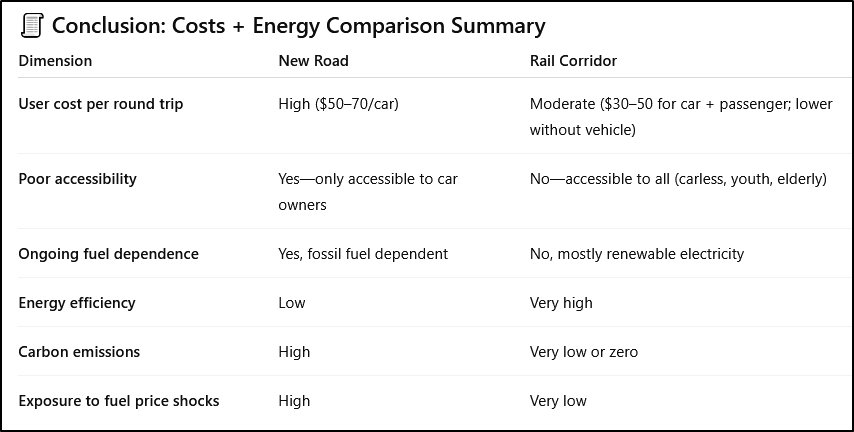

🧾 Conclusion: Costs + Energy Comparison Summary

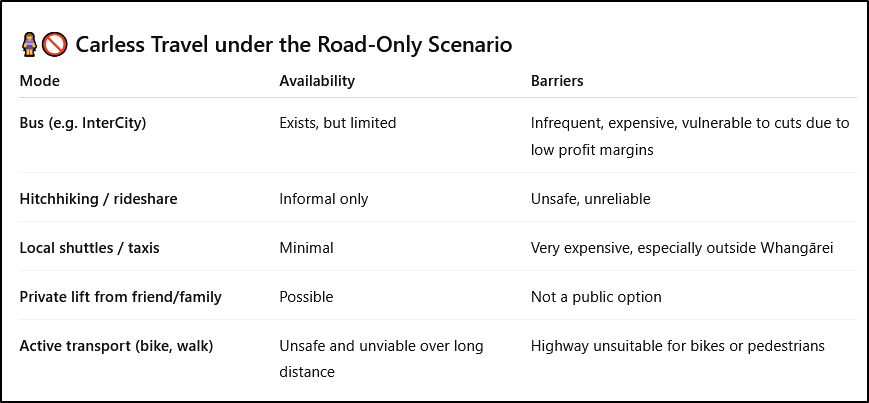

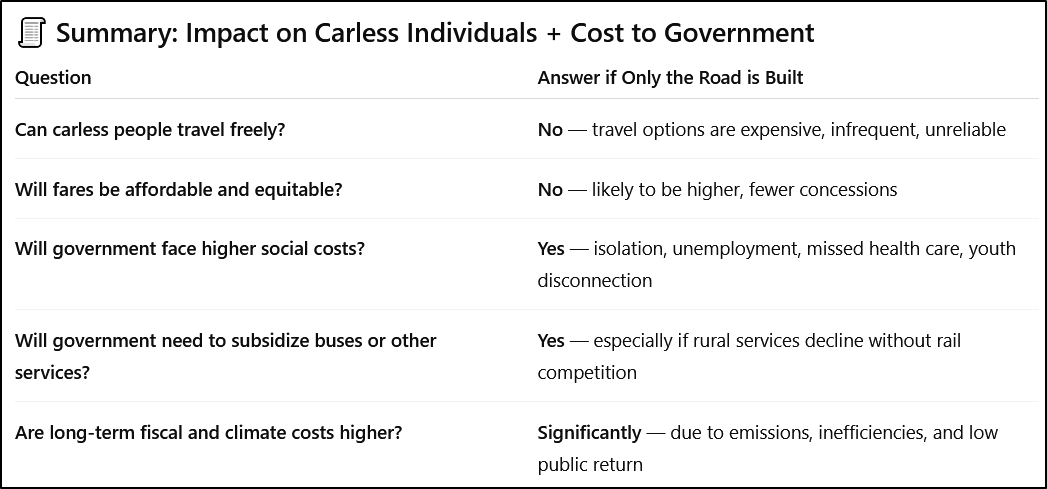

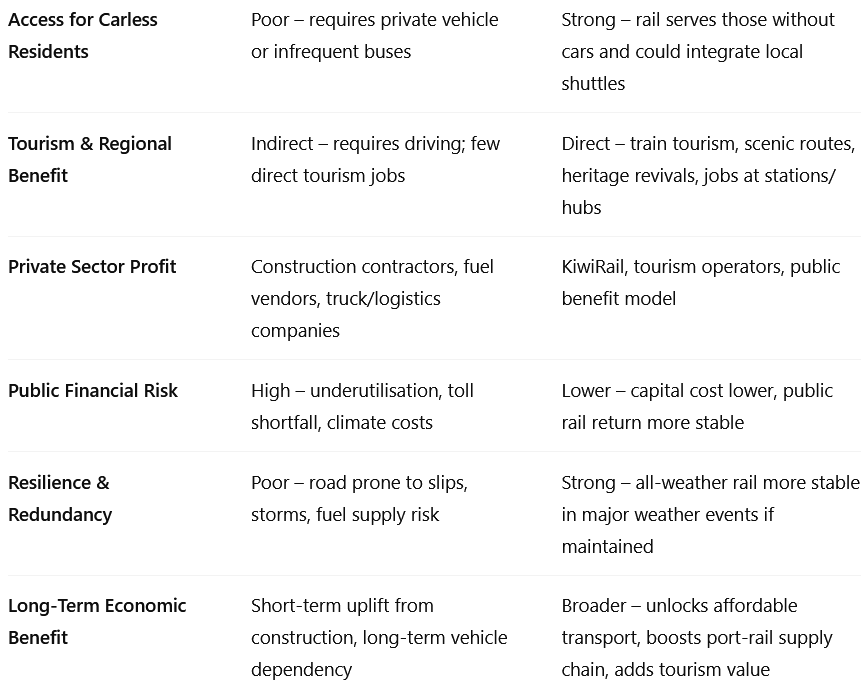

❓ Will carless people still be able to travel between Northland and Auckland if only the road is built?

Technically yes—but practically, with major disadvantages:

🧍♀️🚫 Mobility of the Population under the Road-Only Scenario

Between 10 and 20% of the populations of Auckland and Northland officially do not own a vehicle. These are mostly the young, the old and the poor and the disabled.

📌 Bottom line: Without rail, carless individuals (including elderly, youth, low-income, and disabled) are effectively dependent on rare bus services or others with cars.

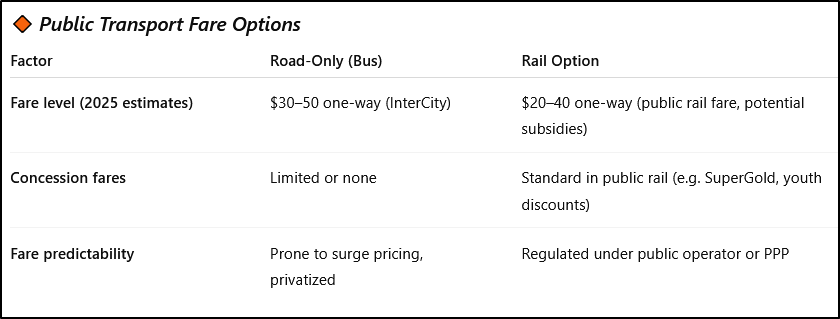

💰 Fare & Government Cost Differences: Road vs. Rail

🔸 Public Transport Fare Options

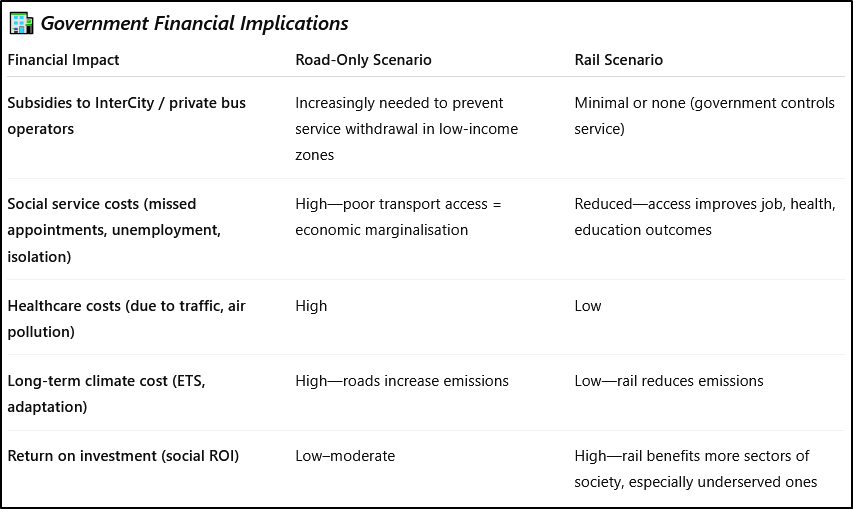

🏦 Government Financial Implications

🧮 Estimated 30-year government losses (inefficiencies, missed opportunities, subsidies, externalities):

Road-only scenario: $3–5 billion in indirect losses

Rail scenario: ~$1–2 billion (net after fares + higher access)

🧾 Summary: Impact on Carless Individuals + Cost to Government

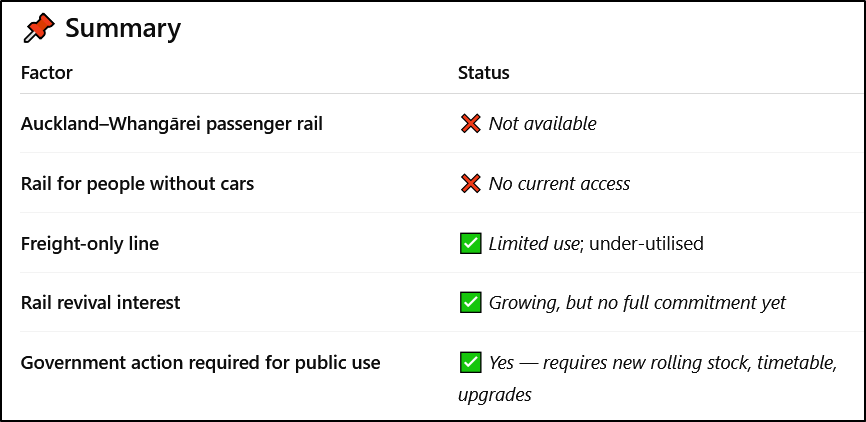

🚆 Is there rail access between Northland and Auckland at present?

No — not for passengers. Only limited, disrupted freight service exists.

🛤️ Current State of Rail Access to Northland (2025)

1. Passenger Services

No regular passenger rail operates between Auckland and Northland.

Last passenger service (Northland Express) ceased in 1976, with brief tourist revival attempts in the 1990s–2000s.

Helensville–Whangārei and Dargaville lines remain freight-only and partially disused.

2. Freight Rail

The North Auckland Line (NAL) runs from Westfield (Auckland) to Whangārei.

Partially operational for low-volume freight, but:

Steep grades, tight curves, and outdated tunnels limit capacity.

Bridges and tunnels north of Swanson needed major repair or replacement.

KiwiRail has periodically mothballed parts due to low commercial return.

Upgrades to reopen the Otiria–Whangārei section are under discussion, but progress is slow and politically uncertain.

3. Potential for Rail Revival

In 2020–21, $100 million+ was allocated to upgrading the North Auckland Line, but this was:

Focused on freight revival (especially logs, dairy, containers),

Not extended to full passenger capability or electrification.

No government has committed to a full Auckland–Whangārei passenger rail project.

📌 Summary

Just who is this government representing?

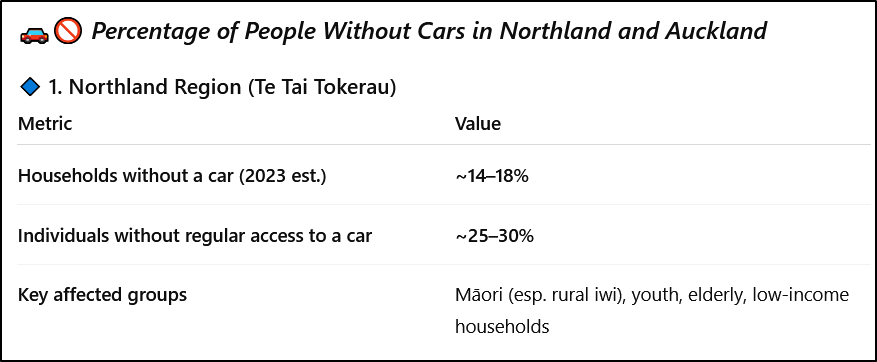

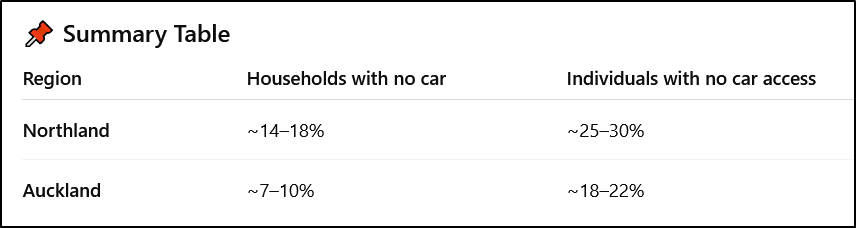

🚗🚫 Percentage of People Without Cars in Northland and Auckland

🔹 1. Northland Region (Te Tai Tokerau)

Northland has one of the lowest median incomes in New Zealand.

In many rural communities, car ownership is unaffordable or unreliable (shared vehicles, no WOF, fuel costs).

Lack of public transport means carlessness = transport deprivation.

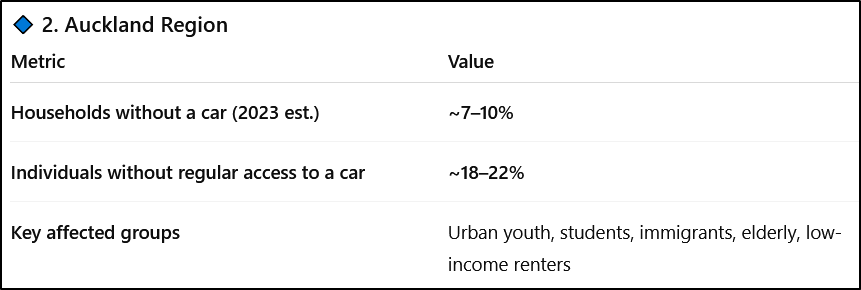

🔹 2. Auckland Region

Auckland has better public transport than Northland, but still heavily car-dependent.

Outer suburbs and South Auckland have lower car ownership rates, correlating with economic hardship.

📌 Summary Table

These figures mean that tens of thousands of people in both regions cannot benefit from a road-only transport investment, unless extensive public bus subsidies are added (which have historically been unreliable).

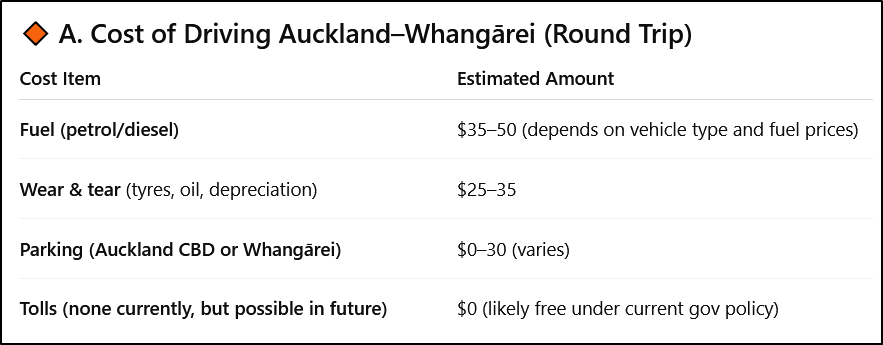

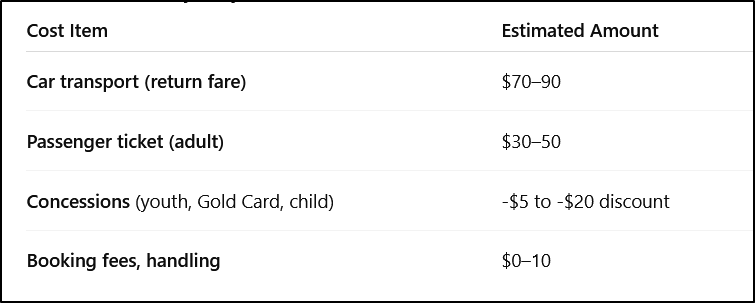

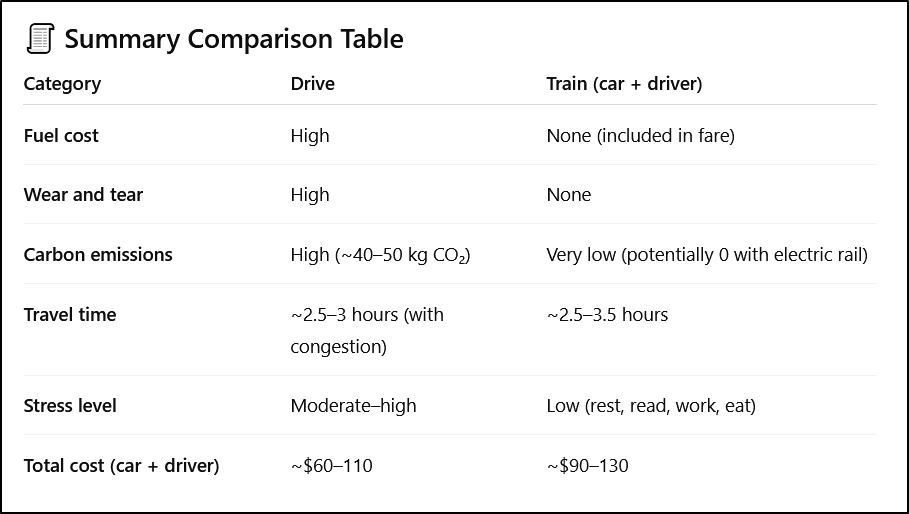

🚗💸 Cost Comparison: Taking a Car on a Train vs Driving (Auckland ⇄ Whangārei)

We'll compare two options:

A. Drive your car the full distance (~170 km one way)

B. Put your car on a train (vehicle ferry-style) and ride as a passenger

🔸 A. Cost of Driving Auckland–Whangārei (Round Trip)

✅ Total (round trip):

~$60–$110 per trip (excluding unpaid time, congestion, or carbon cost)

🔸 B. Estimated Cost of Taking a Car on the Train

Using benchmarks from similar services like:

Interislander & Bluebridge ferry car decks

European Alpine car-on-train corridors

Australian Sydney–Perth motorail

✅ Total (round trip):

~$90–130 for car + driver

(~$30–50 for driver only, if leaving car behind)

🧾 Summary Comparison Table

⚠️ Notes:

Taking your car on the train instead of driving is $20-$30 more expensive up front, but it:

Avoids driver fatigue and road risk

Cuts emissions drastically

Can be more comfortable and inclusive

Provides 2-3 hours of extra available time.

For frequent travelers, bulk passes or subscriptions could reduce the train cost per trip significantly.

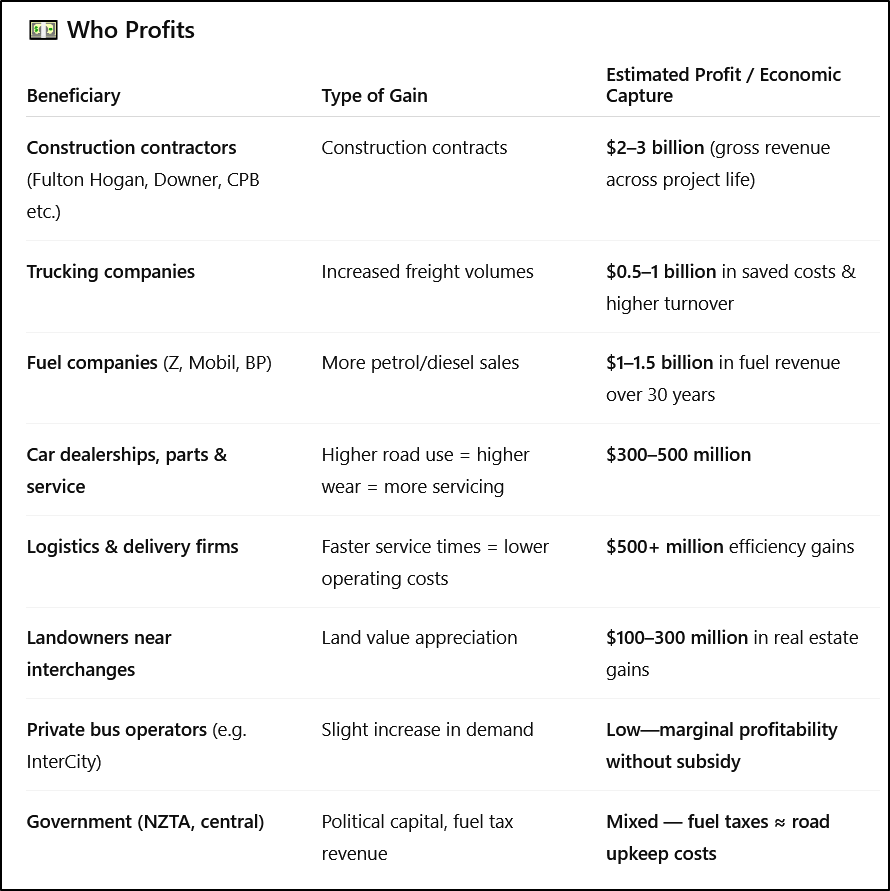

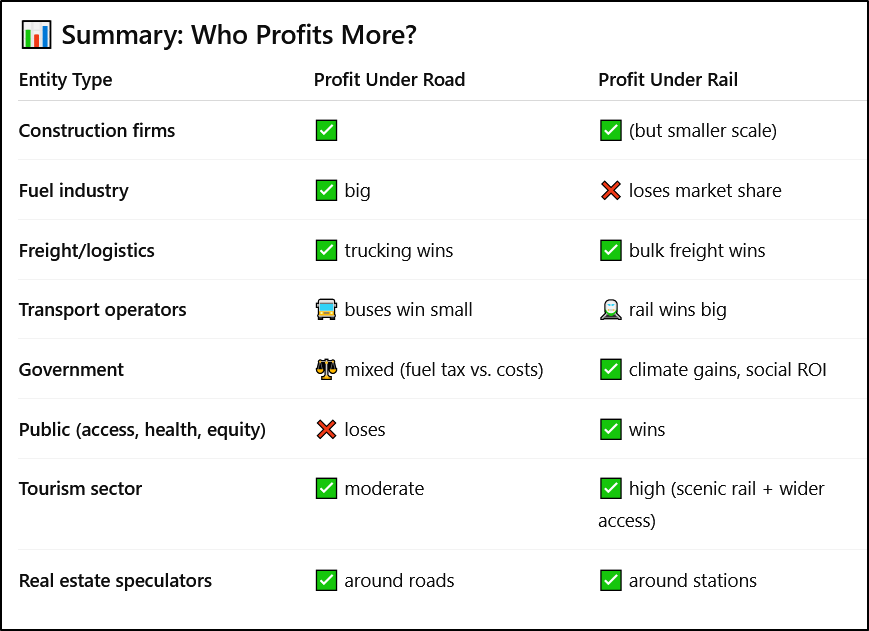

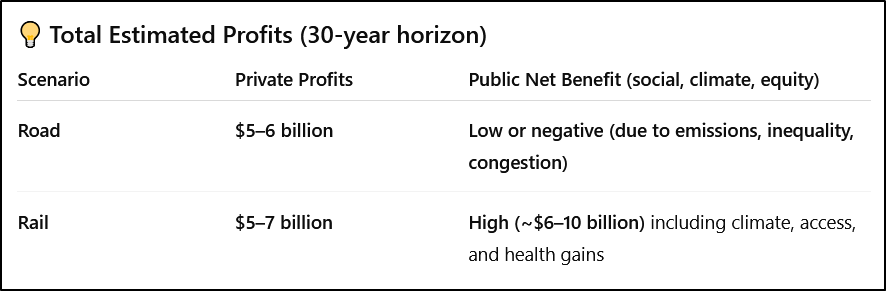

💰 Who Profits from Each Scenario: Road vs. Rail (Auckland–Whangārei)?

This breakdown shows the primary financial and political beneficiaries under each scenario, and estimated profit or economic capture over 30 years.

Estimates are expressed in NZD and derived from public transport economics, infrastructure modelling, and commercial operator margins.

🚧 Scenario A: Four-Lane Highway Only

💵 Who Profits

⚠️ Losers:

Carless population, climate, public health, low-income users, local councils (maintenance burden)

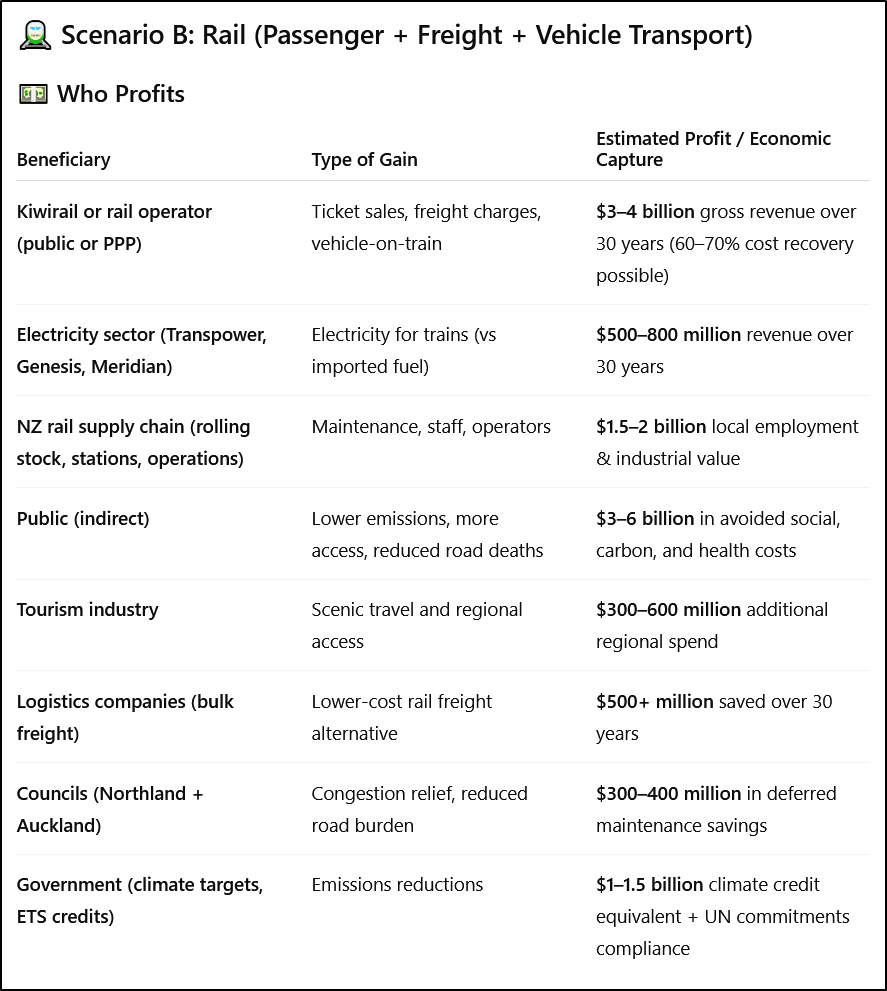

🚆 Scenario B: Rail (Passenger + Freight + Vehicle Transport)

💵 Who Profits

⚠️ Losers:

Fuel companies, road haulage firms (lose monopoly on Northland freight), car sales & service businesses (slightly lower car use)

📊 Summary: Who Profits More?

💡 Total Estimated Profits (30-year horizon)

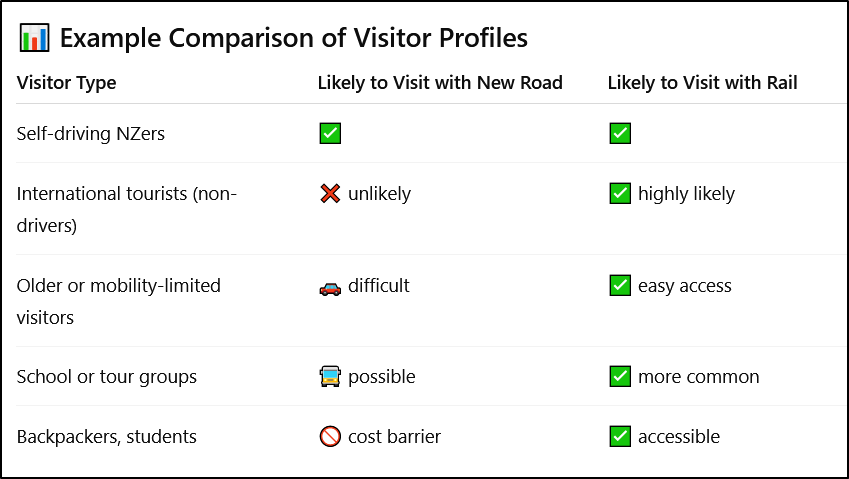

❓ Why would regional tourism spending increase with rail but not with a new road?

This comes down to how people travel, who can travel, and what they spend money on when they get there. Rail changes who visits, how long they stay, and what they spend, in ways roads typically do not.

Northland is the only region in New Zealand with a sub-tropical climate. Summer is from November to early April with the hottest months being January and February. The top of Northland known simply as the 'Far North' is famous for beaches and in particular the longest beach in New Zealand, called the 'Ninety Mile Beach'. It covers the entire western coast of the Far North and has huge sand dunes which make parts of this coastline resemble the Sahara Desert. Over on the more sheltered east coast, the coastline is indented with many idyllic sandy beaches and bays, which include such gems as Karikari beach, Great Exhibition Bay which is claimed to have the purest deposit of silica sand in the world, and sacred Spirits Bay.

Further south of the Far North but still on the east coast, is one of New Zealand's most popular tourist attractions, The Bay of Islands. Boat trips available from the towns of Paihia and Russell and will take you out to see some of the 150 sub-tropical islands dotted in the bay.

The town of Waitangi is located here and has special importance to New Zealand because it is here that the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840. This treaty is the the founding document of the nation.

🚆 Rail Generates More Regional Tourism Spend Because:

1. Rail Attracts Visitors Who Wouldn’t Drive

Many international tourists, urban New Zealanders, and youth prefer not to rent or drive cars—especially after long-haul flights.

Rail opens access to non-drivers: older tourists, students, lower-income domestic travelers, families, disabled persons.

Road improvements benefit people who already travel, but rail brings new travelers who otherwise wouldn’t come at all.

2. Rail Promotes Multi-Night Stays

Road travelers often “do a loop” or pass through places quickly, especially if the road is fast.

Rail users tend to stay longer in towns where the train stops, boosting accommodation, hospitality, and attractions.

🚉 Each station becomes a tourism node. Towns like Dargaville, Kaikohe, Ruakaka, and Whangārei benefit only if trains stop, but not if cars just speed past on new highways.

3. Rail Travel Encourages Local Spending

Car travelers bring their own transport, so they’re less likely to spend on:

Local tours, guides

Local shuttle buses, bike hire

Cafes/restaurants (many eat roadside or pack food)

Rail tourists are captive to the destination: they explore on foot or by local services, which boosts local business.

4. Rail is a Tourism Attraction in Itself

Scenic trains generate their own demand: views, comfort, nostalgia.

Examples:

TranzAlpine: one of NZ’s top-rated tourism experiences.

Taieri Gorge, Coastal Pacific: tourism-dependent services.

A Northland line could offer beach, forest, and cultural rail experiences not possible by car (e.g. interpretive services, guided routes, onboard dining).

5. Tourism Marketing and Packaging

Trains make it easier to package deals (e.g. rail + stay + attraction), especially for international visitors.

Rail allows seasonal, off-peak promotions, unlike highways, which have little influence over demand timing or quality.

📊 Example Comparison of Visitor Profiles

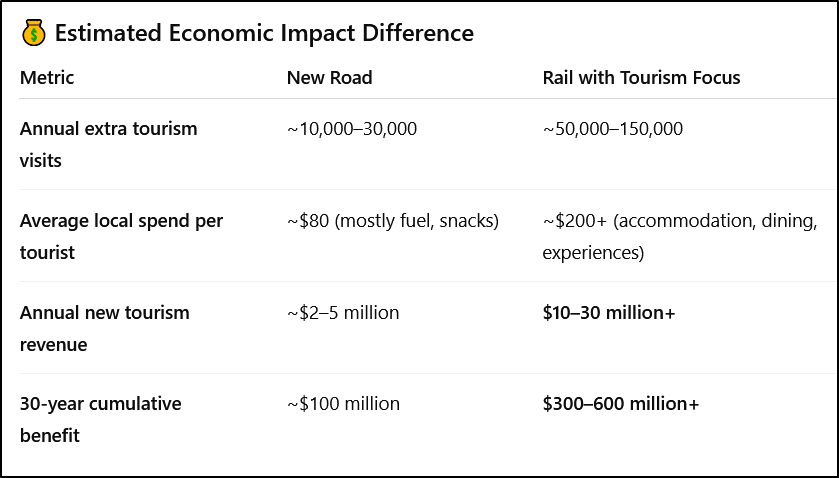

💰 Estimated Economic Impact Difference

📌 Conclusion:

The road improves access for existing drivers, but does not substantially expand the tourism base.

Rail creates a new class of visitors, especially from overseas and underserved domestic groups, and amplifies regional spending through longer stays and higher per-visitor spend.

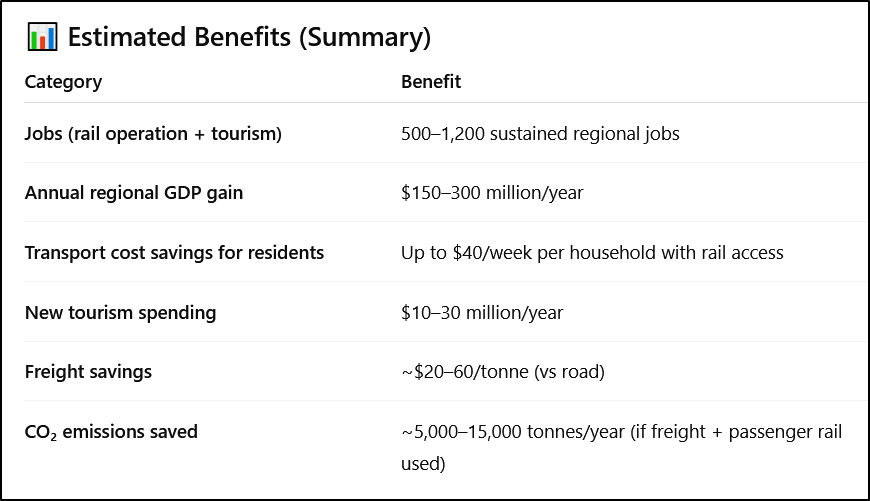

❓ What benefits would rail—compared to road—bring to the Northland economy and people?

A properly designed Northland rail line would deliver wider and deeper economic, social, and environmental benefits than a new highway alone. Here's a detailed breakdown:

🌍 1. Economic Benefits for Northlanders

🔹 a) Job Creation

Construction phase: Hundreds of jobs in rail infrastructure, especially if stations and freight facilities are built in rural centres.

Ongoing operations: Train operations, maintenance, logistics, tourism support, hospitality.

Tourism multiplier: Hotels, cafes, tour operators, and shuttle services benefit in towns with stations.

📈 Rail brings long-term, service-sector jobs to towns like Kaikohe, Dargaville, Ruakaka, and Kawakawa.

🔹 b) Boost to Regional Businesses

Rail makes it cheaper to export goods (e.g., timber, dairy, fish, horticulture) and import bulk supplies.

Better access to Auckland markets = growth for Northland producers.

Carriage of perishable goods, like seafood, could be made faster and more reliable with cold-chain compatible rail.

🔹 c) Tourism Revenue Growth

As detailed earlier, rail brings new types of tourists:

Non-drivers

Overseas visitors

Tour groups

These tourists spend more locally on accommodation, activities, food.

Rail towns often develop new tourist identities—e.g., scenic rail stops, cultural trails.

🚶♀️ 2. Social Benefits for Northland Residents

🔹 a) Mobility for the Carless

In Northland, 15–30% of households lack access to a car (higher in Māori and rural communities).

Rail provides affordable, safe long-distance transport:

For youth, elderly, students, disabled, low-income residents.

Enables travel to Auckland for work, education, hospital visits, or whānau connection.

🔹 b) Safer Travel

Rail travel has significantly lower accident and death rates than rural driving.

Northland roads are among NZ’s most dangerous—rail offers a life-saving alternative for vulnerable users.

🔹 c) Reduced Cost of Living

Bulk freight delivery to regional centres could lower consumer goods prices in remote towns.

Families without cars save hundreds per month on travel costs if there's rail access.

🔹 d) Regional Equity

Northland is historically under-served in infrastructure investment.

A rail link would show commitment to fair development and treaty-aligned service delivery.

Stations can be Māori-led hubs (e.g., cultural tourism, artisan markets, kai stalls), delivering mana motuhake (self-determination) through rail-connected enterprise.

🌱 3. Environmental and Resilience Benefits

🔹 a) Lower Emissions

Rail uses less energy per tonne or passenger than road.

A modern electric/diesel hybrid or hydrogen line would cut:

Transport sector CO₂ emissions

Noise and pollution in towns

Fewer trucks = less wear on rural roads and bridges.

🔹 b) Climate Resilience

Rail offers a redundant transport route during weather or fuel crises.

Helps Northland cope with:

Flooded roads (frequent in storms)

Petrol supply issues

Civil defence emergencies

📊 Estimated Benefits (Summary)

=================

Here is a direct comparison of the estimated economic, social, and environmental benefits of the proposed rail vs road investment into Northland, using the same categories and assumptions for both.

🔁 SUMMARY COMPARISON: Rail vs Road Benefits

🔍 Ongoing employment in Rail Infrastructure

This estimate reflects:

Track repair and upgrade across ~250+ km (some disused, some in poor state)

New station builds or refurbishments (potentially 5–12 locations)

Logistics hubs for freight at Whangārei, Ruakaka, Otiria

Bridge and tunnel reinforcement

Signalling and electrification/hybrid upgrades if applicable

🔧 Rail construction is labour-intensive because:

It involves precision civil and mechanical works

Often requires simultaneous crews for earthworks, track laying, bridge repair, and ballast placement

Unlike roads, rail projects may be done in segments with rotating teams across years

🛣 By contrast, highway projects are increasingly mechanised, and contracted to large firms who bring teams from outside the region. Most of the work is earthmoving, grading, surfacing, and barrier construction.

🧭 Key Takeaways

Rail has higher job creation, both in construction and long-term regional employment.

Rail offers significantly more social inclusion, lower travel costs, and climate advantages.

The road may bring quicker drive times—but only for those who already own vehicles.

Economic impact is broader with rail, especially for tourism, freight efficiency, and town development.

Lower cost of rail

Reviving and expanding the rail link to Northland can cost less than the proposed highway for several structural, geographic, and economic reasons. Here's how and why:

🛠️ Cost Comparison Summary

🔍 Why Rail Costs Less (Despite the Distance)

1. Existing Track Already in Place

~90% of the North Auckland Line (Auckland to Whangārei) exists and is usable or restorable.

Key investments are track relaying, bridge reinforcement, and modern signalling — cheaper than full roadbed construction.

Sections already upgraded (e.g., Swanson–Helensville) reduce initial outlay.

2. Minimal Land Acquisition

Rail corridors mostly already owned or protected.

Road projects require buying private land, often at high cost due to proximity to Auckland and coastal settlements.

3. Narrower Footprint = Lower Earthworks

Rail needs a ~10m corridor vs. ~30–60m for a 4-lane highway.

This means less cutting through hills, fewer massive bridges, and reduced environmental disruption.

4. Lower Carbon and Compliance Costs

Road carbon offset and environmental mitigation costs are growing due to national net-zero targets.

Rail projects may qualify for emissions reduction credits or climate finance, lowering net public spend.

📉 Cost-Saving Measures for Rail

Staged Development:

Start with freight & basic passenger services.

Expand to car-carrying services and higher frequency once demand grows.

Rolling Stock Leasing:

Lease rather than purchase trainsets to reduce upfront capital costs.

Public–Private Partnerships:

Engage logistics operators and tourism firms in funding stations and services.

Re-use and Retrofit:

Reinforce rather than rebuild many tunnels and bridges.

Use modular, low-cost station designs and adaptive reuse of depots.

🧭 Final Point

Even with upgrades, rail is a restoration project, not a full greenfield build like a new highway. Combined with the higher social, environmental, and economic returns per dollar spent, rail offers more strategic value for less public expenditure, especially in a region like Northland with:

High deprivation and low car ownership,

Urgent need for economic regeneration,

And a future dependent on climate-resilient, inclusive infrastructure.

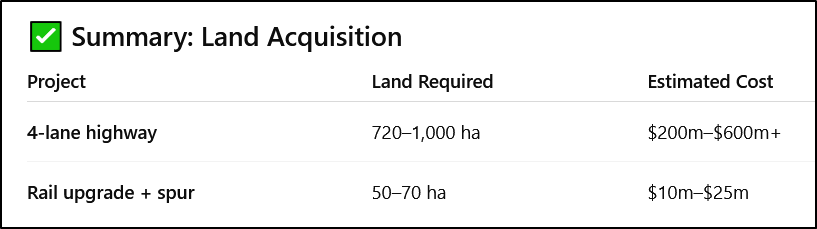

📐 Estimated Land Acquisition Required: Road vs Rail (Auckland–Whangārei Corridor)

🛣️ New 4-Lane Highway (Warkworth to Whangārei)

Route length: ~160 km

Corridor width: 30–60 m (avg ~45 m)

Estimated land required:

> 720 hectares to 1,000 hectares (7.2–10 km²)

🏷️ Cost of land acquisition (conservative estimate):

Average rural Northland land values (2024): $50,000–$150,000/ha

In peri-urban and lifestyle-block areas: $200,000–$500,000/ha

Total cost range:

▶️ $200 million to $600+ million, depending on route alignment and opposition.

Additional costs:

Compensation for homes or businesses displaced

Legal delays, compulsory acquisition costs

Māori land and Treaty-related negotiation costs

🚆 Rail Upgrade (North Auckland Line) + Marsden Point Spur

Existing Corridor:

Most of the North Auckland Line already exists in KiwiRail ownership.

Land acquisition required only for:

Marsden Point Spur (~19 km) – mostly greenfield.

New passing loops, station platforms, terminals.

Potential station carparks and freight facilities.

Estimated land required:

Spur corridor (20m x 19 km): ~38 hectares

Stations + terminals: ~10–20 hectares

Total land required: ~50–70 hectares

Land acquisition cost:

Mainly industrial or rural-zoned land.

Cost estimate:

▶️ $10 million to $25 million total

✅ Summary: Land Acquisition

⚠️ Additional Considerations

Highway land takings may provoke stronger community or iwi resistance due to disruption.

Rail uses narrower corridors and avoids high-impact zones more easily.

Opportunity cost is higher for roads: land permanently removed from farming or forestry.

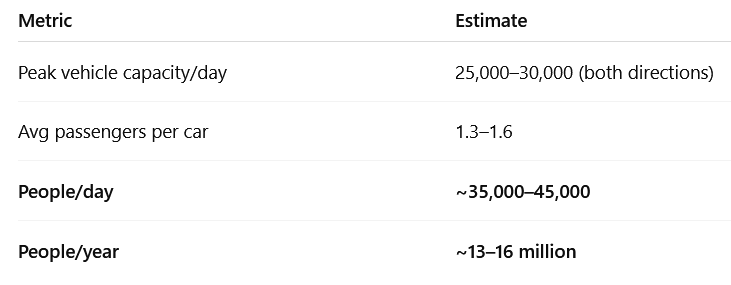

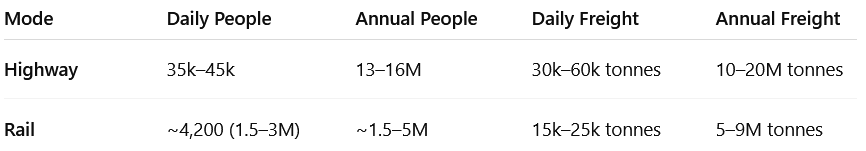

🚄📦 Estimated Transport Capacity: Rail vs Road (Auckland–Whangārei Corridor)

🛣️ New 4-Lane Highway (Warkworth to Whangārei)

🚗 People (Passenger Vehicles)

➡️ Primarily benefits those who own cars or afford long-distance buses.

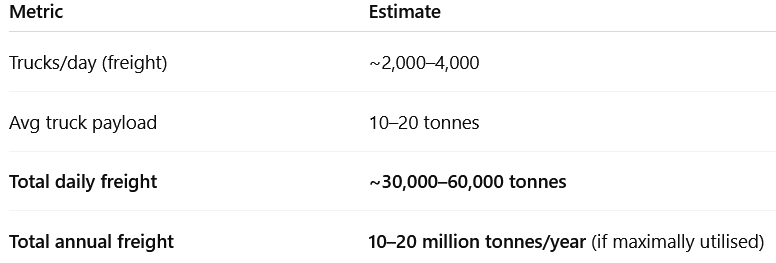

🚚 Freight Trucks

🚆 Modernised Rail (North Auckland Line + Marsden Spur)

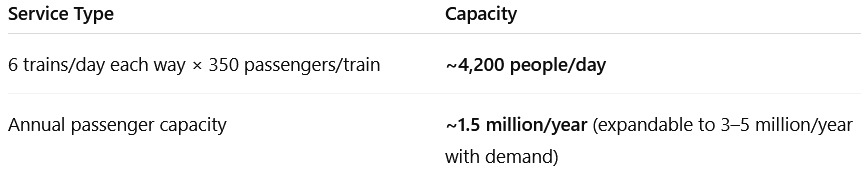

🚄 Passenger Service (Auckland–Whangārei rail + regional stops)

Fares could be subsidised for affordability

Allows access for carless people, students, elderly, tourists

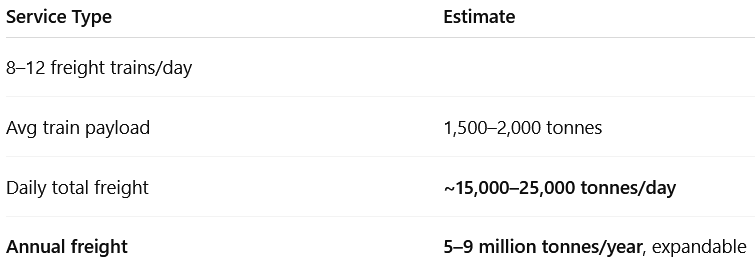

🚛 Freight Rail

More efficient per tonne than road

Ideal for logs, dairy, containers, fuel to/from Marsden Point

📊 Comparison Summary

🔍 Key Notes:

Road has higher volume, but rail enables access for low-income, carless, and freight-intensive sectors.

Road usage is limited by fuel cost, congestion, car access, emissions.

Rail is expandable, more energy efficient, and allows modal shift from trucks (less road damage, lower emissions).

Every freight train can replace ~60–80 trucks on SH1.

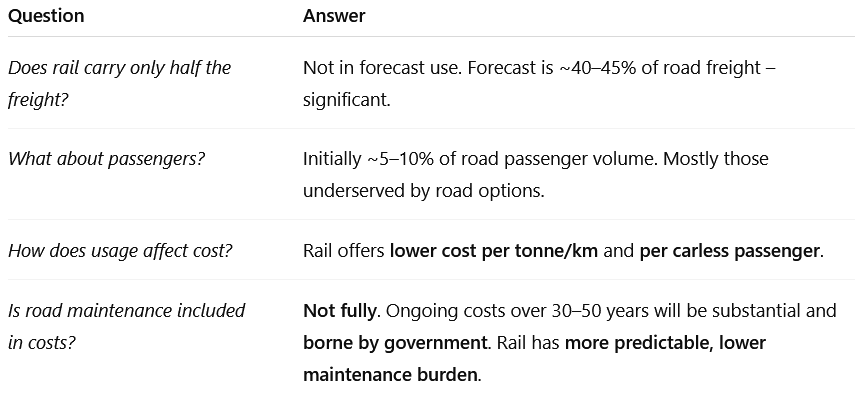

Forecast vs Capacity - cost- benefit breakdown

Below is a breakdown that distinguishes between capacity and forecast use, explains implications for cost-effectiveness, and assesses whether road maintenance is included in the proposed highway costings.

🚦 Forecast vs Capacity: Rail vs Road

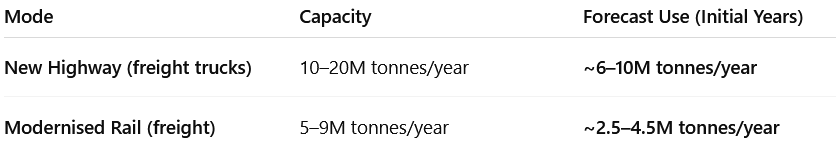

📊 1. Freight Forecasts

➡️ Rail would carry ~40–45% of highway freight initially (not just 50% capacity, but almost half of expected usage).

✅ Rail volume likely to grow over time, especially if carbon pricing rises or Marsden Point Port expands.

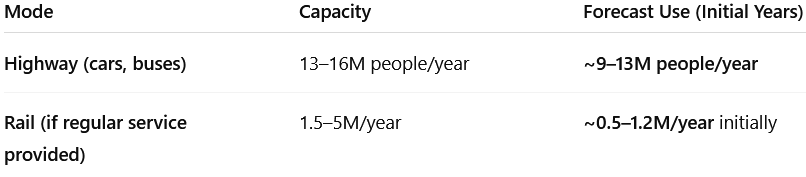

👥 2. Passenger Forecasts

➡️ Rail: 5–10% of passengers in early years – primarily:

Carless individuals

Low-income groups

Students

Tourists

Elderly

But:

Every rail passenger is one less subsidised road user

Rail use is price-responsive (can expand with affordability or fuel cost spikes)

💸 3. Costs vs Usage Value

➡️ Rail offers much lower per-unit costs for freight and fixed-cost public transit for people who cannot afford cars or fuel.

🔧 4. Road Maintenance – Is It Included?

No — not fully.

NZTA road costings for the new highway project cover:

Construction

Immediate corridor acquisitions

Some limited early maintenance

But they do not fully include:

20–30 years of wear and tear maintenance

Bridge, pavement, and slope reinforcement in difficult terrain

Cost of induced traffic (more vehicles = more maintenance)

Cost of parallel road upgrades (for feeder traffic)

In contrast:

Rail forecasts include ongoing infrastructure upkeep, often bundled into capital amortisation + Kiwirail OPEX.

🧾 Summary of Key Points:

🔧 1. Ongoing Maintenance of the Old Road (SH1) if New Highway Is Not Built

If the proposed new highway is not built and the existing SH1 (via Brynderwyns, Dome Valley, etc.) remains the primary corridor:

🛠 Estimated 20-Year Maintenance Costs (Status Quo Route):

These figures include:

Reactive slip management (like March 2023 closures)

Ongoing repaving, barrier and safety realignments

High maintenance costs due to freight-heavy traffic loads

🧾 Important: This cost is in addition to the rail upgrade, if only rail is built. The road remains in use regardless, so maintenance must continue.

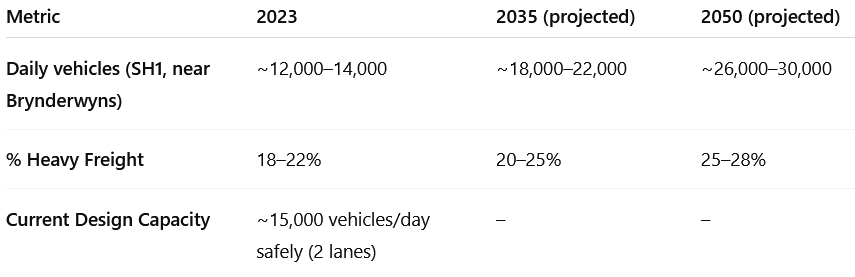

🚚 2. Capacity of Existing Road to Cope if Only Rail Is Built

🔄 Expected Traffic (Without New Road):

🧱 If Rail Is Upgraded and Used for Freight:

If rail removes 40–50% of heavy freight, then:

Road traffic grows slower

Peak congestion is delayed by ~10–15 years

Road can remain functional with targeted upgrades (passing bays, slip-proofing, better surfacing)

However:

Weekend holiday congestion will worsen

Journey times remain vulnerable to slips, closures

Freight costs increase over time with diesel and road-user charges

🔍 Summary

Comparative analysis table for the two main scenarios under consideration for the Auckland–Northland corridor:

🚧🚆 Comparison: “New Highway Only” vs “Rail Upgrade + Maintain Existing Road” across 10–20 indicators (jobs, emissions, resilience, tourism, land use, etc.)

🧾 Notes:

Rail freight is cheaper per tonne, especially for bulk goods (timber, aggregates, dairy).

Passenger demand for rail depends on timetable quality, reliability, and integrated connections.

Dual investment (rail + SH1 maintenance) is cheaper and fairer than building a $6b highway for drivers only.

Summary Comparison: Road vs. Rail (Northland–Auckland)

Cost to Government Over 30 Years (NZD, 2025–2055)

Here's a 30-year cost-to-government estimate comparison between the proposed four-lane highway and a modernised Northland–Auckland rail line, using available data, conservative assumptions, and long-term infrastructure norms in New Zealand:

Key Notes:

Road maintenance is much more expensive over time because the highway must support heavy trucks and tens of thousands of cars daily. Maintenance of the existing SH1 corridor would still be needed if not replaced.

Rail's capital cost is lower, and KiwiRail already owns most of the corridor, avoiding massive land purchases or new consents.

Climate resilience is a growing cost burden. Rail lines, once stabilised, are far more resilient to flooding and slips than roads—especially in hilly Northland terrain.

Rail also reduces pressure on roads, cutting future government spending on expansions, bridge replacements, and bypasses.

My conclusion - what next?

Now. The above may be a load of rubbish - “ChatGPT can make mistakes”. But it looks convincing enough to me.

Whatever the cost analysis, the proposal to keep the rail unavailable to the whole northern end of our country is not opening opportunities. It is firmly closing them. Because without public transport or freight available to the 30% poor, to access opportunities, there is no opportunity to break out of poverty.

I’d like our media to investigate it,

I’d like this government to answer it,

And I’d like our opposition parties to make a commitment to their position on it.

That’s the only way voters like me can exercise our democratic rights - to direct our representatives what we want. Instead of the other way round.

We need information.

We need transparency.

We don’t need governments that go off and do what they want to do.

We need governments that consult us, as their employers, and do what is in our interests, not theirs.

That’s what we pay them for.

x

Several other considerations. In the last week alone, two logging trucks have rolled putting unnecessary purchase on local rescue response services and associated costs to businesses due to traffic problems.

There is a movement in place to restore rail to the far north.

There is an intercity bus service that charges less than the cost of petrol to Auckland.