How Big Money Destroys Co-operatives | Knowledge is Power

Co-operatives and worker share structures are the way that wealth is received by those who produce it - not by extractors. Here's a comparison of success in Italy, and destruction in the UK.

Co-operatives and worker share structures are the way that wealth is received by those who produce it - not by extractors. Here’s a comparison of success in Italy, and destruction in the UK.

You could call co-operatives true capitalism - in contrast to the rentier capitalism model we know, which extracts rent, aka private “taxes”, aka “profit” from the workers who produce wealth, for the privilege of being employed.

Italian co-operative success stories

Here’s a lovely video showing that co-operatives are alive and thriving in Italy. From food producers to heavy industry, all benefit in proportion to their contribution. They choose their contribution and their earnings.

The UK co-operative failure story

Contrast what happened to the Triumph worker buyout in the UK: Triumph (Meriden Motorcycle Cooperative)

What happened:

In 1974, workers at Triumph’s Meriden plant in the UK occupied the factory to prevent closure.

With Labour government support, they formed the Meriden Motorcycle Cooperative, which was majority worker-owned and worker-controlled.

The cooperative produced Triumph motorcycles through the late 1970s.

Outcome:

It survived nearly a decade (1974–1983), which is longer than many people realise.

However, it was chronically under-capitalised, carried legacy production constraints, and faced intense competition from Japanese manufacturers with superior scale, productivity, and technology.

Government support declined in the early 1980s, credit tightened, and the cooperative ultimately collapsed into liquidation in 1983.

The Triumph brand later re-emerged under new private ownership, entirely disconnected from the worker cooperative.

This is the canonical UK example of workers “buying” an automotive manufacturer.

It demonstrated that worker control could sustain production for years, but also exposed how capital intensity, global competition, and macro-policy choices can overwhelm cooperative ownership absent long-term financial and industrial support.

UK Nationlisation: also a failure

Contrast: British Leyland / Austin Rover / Rover Group

What did not happen:

British Leyland was nationalised, not bought by its workers.

There was no full worker buy-out of any British mass-market car manufacturer.

Later iterations (Austin Rover, Rover Group) had limited employee share schemes, but control remained with the state or private owners (eventually BMW).

Outcome:

British Leyland was progressively restructured, downsized, and privatised.

Most marques disappeared or were sold off; mass British car manufacturing largely collapsed rather than becoming worker-owned.

How could Triumph have succeeded? Why couldn’t it borrow?

“Chronically under-capitalised,” sounds a bit ironic these days, after decades of undercapitalised companies becoming successful.

“Undercapitalised” is not a neutral technical description. In Triumph’s case it reflected political and financial exclusion, not an intrinsic economic impossibility. Many successful firms have begun undercapitalised; the difference is whether they are allowed to remain so while scaling.

I will address this in three parts: (1) what “undercapitalised” actually meant at Meriden; (2) why it could not borrow; and (3) what a plausible success path would have required.

1. What “chronically under-capitalised” meant in practice

Meriden’s problem was not that it lacked customers or a viable product.

Triumph motorcycles had strong brand recognition and export demand, especially in the US.

Early cooperative production met sales targets.

Labour productivity improved materially after worker control.

“Undercapitalised” meant instead:

No access to patient capital for retooling, automation, or model renewal.

Insufficient working capital buffers to survive demand fluctuations.

Legacy plant constraints inherited from private ownership, without funds to modernise.

In other words, Triumph was forced to operate a 1970s mass-manufacturing business on a cash-flow-only basis, which is structurally untenable in heavy industry.

By contrast, firms we now celebrate for “bootstrapping” almost never face this constraint in capital-intensive sectors; they either receive bank credit, state guarantees, or equity injections once viability is demonstrated.

2. Why Triumph could not borrow

This is the core issue, and it is not accidental.

(a) No collateral acceptable to banks

The cooperative did not own the land or plant outright in a way banks were willing to treat as collateral.

Much of the equipment was obsolete or encumbered.

Worker-owned shares were explicitly non-transferable, eliminating conventional equity security.

From a banking perspective, there was nothing to seize. But there was more than today’s “bootstraps”.

(b) Ideological credit rationing

Banks did not treat Meriden as a normal commercial risk.

Worker control violated prevailing assumptions about governance, discipline, and enforceability.

Lending to the cooperative would have legitimised a model the financial sector strongly opposed.

Risk premiums were set effectively at infinity.

This is not conjecture; it aligns with broader UK credit allocation patterns of the late 1970s, where industrial policy was increasingly subordinated to financial discipline.

(c) Government refused to act as lender of last resort

Crucially, the state chose not to backstop the cooperative.

Initial government support, from a so-called Labour government, was limited, conditional, and time-bound.

No standing guarantee for long-term borrowing was provided.

When macro policy tightened under the early Thatcher government, support was withdrawn entirely.

Private firms in comparable distress routinely survive this phase via:

State guarantees

Directed credit

Soft loans

Implicit bailouts

Meriden was denied all four.

3. How Triumph could have succeeded

A realistic success path did not require miracles—only parity of treatment.

(1) Transitional public banking or credit guarantees

A publicly backed industrial bank could have provided long-term, low-cost finance.

Even modest guarantees would have unlocked private lending.

This is how post-war reconstruction succeeded across Europe.

(2) Time to retool

Japanese competitors did not win solely through “efficiency”:

They benefited from coordinated industrial policy.

They enjoyed protected domestic markets and subsidised capital.

Triumph needed:

Modern tooling

Model rationalisation

Supply-chain integration

These are capital problems, not labour problems.

(3) Explicit recognition of worker equity

If the state had:

Recognised collective labour claims as equity-like instruments, or

Issued redeemable public shares tied to output and exports,

then Meriden’s balance sheet would have looked “bankable” almost overnight.

(4) Stable macro conditions

High interest rates and fiscal contraction disproportionately punish firms without accumulated wealth. Triumph was deliberately exposed to this environment while its private competitors were cushioned by prior capital accumulation and financial ties.

The deeper irony

Meriden failed not because worker ownership is inefficient, but because it challenged the allocation of power.

Private undercapitalisation is tolerated because it preserves hierarchical control and financial rents.

Cooperative undercapitalisation is fatal because it threatens them.

In that sense, Triumph’s collapse was less a business failure than a policy choice about who is permitted access to credit.

I. Meriden Triumph vs Japanese motorcycle manufacturers: financing, not “efficiency”

The competitive divergence between Triumph (Meriden) and Japanese producers in the 1960s–70s is routinely misattributed to culture or shop-floor practices. In reality, it was overwhelmingly a capital-structure and credit-allocation divergence.

1. Japanese manufacturers: capital abundance by design

Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki, and Kawasaki operated within a coordinated developmental finance system:

Main-bank lending: Long-term, relationship-based credit insulated firms from short-term cash-flow shocks.

Implicit state guarantees: Banks understood that strategic manufacturers would not be allowed to fail.

Low and stable interest rates: Capital costs were predictable and modest.

Export-linked finance: Foreign exchange earnings reinforced creditworthiness.

Critically, Japanese firms:

Could run losses while retooling.

Could amortise investment over decades.

Could modernise continuously without existential risk.

Their “productivity” gains followed after capital deepening.

2. Meriden Triumph: capital starvation by policy choice

Meriden faced the inverse environment:

No relationship banking.

No lender of last resort.

No state-backed guarantees.

No tolerance for transitional losses.

High and volatile interest rates.

As a result:

Tooling upgrades were postponed.

Model development lagged.

Economies of scale could not be reached.

Any downturn became terminal.

This was not a failure of worker control. It was a failure of financial plumbing.

Had Triumph been financed on Japanese terms—even partially—the outcome would almost certainly have differed.

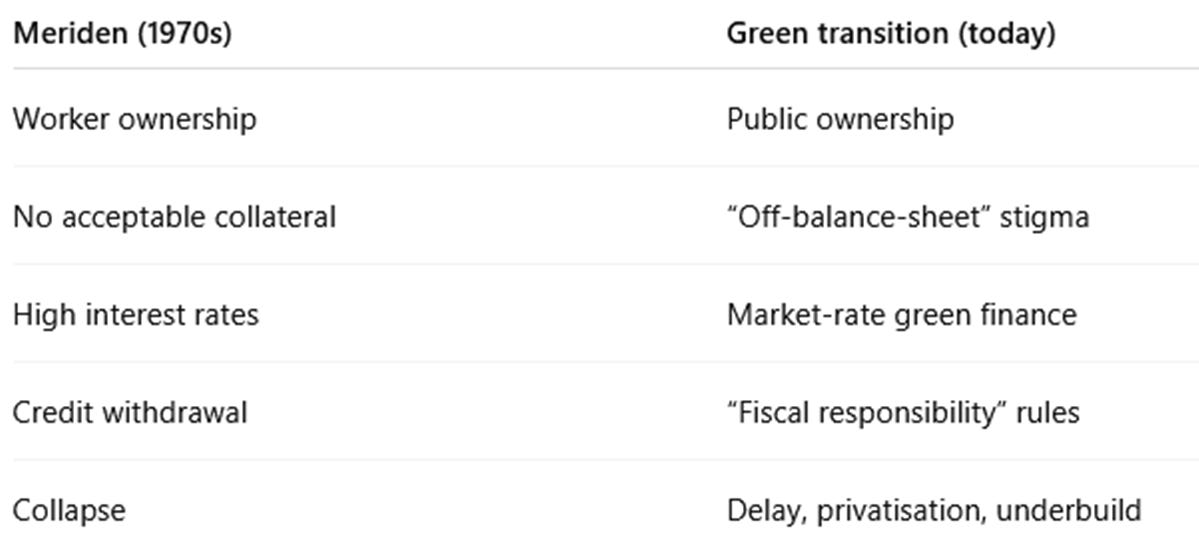

II. From Meriden to the present: the modern “credit strike” against non-private ownership

What happened to Triumph is not historically isolated. The same mechanisms persist today under different institutional language.

1. The credit strike: how it works

A “credit strike” occurs when:

Financing is formally available,

But practically inaccessible due to ownership structure, governance form, or political implications.

This disproportionately affects:

Worker cooperatives

Public utilities

Municipal enterprises

Platform cooperatives

Community-owned infrastructure

The stated rationale is “risk.”

The real issue is control and rent preservation.

2. Contemporary examples

(a) Platform cooperatives

Demonstrate viable demand and operational competence.

Denied venture capital due to lack of extractive exit paths.

Denied bank lending due to non-transferable equity.

Forced into under-scale operation despite proven models.

(b) Public utilities

Borrow at higher rates than private counterparts despite lower default risk.

Required to “commercialise” to access capital markets.

Ultimately privatized to “unlock investment” that could have been provided publicly at lower cost.

(c) Green transition infrastructure

Publicly owned renewables face higher financing costs than private ones,

despite lower long-term risk.Private capital is subsidised to do what public balance sheets could do directly.

3. The continuity with Meriden

The Meriden Cooperative failed under conditions that remain structurally intact:

Labour can organise production.

Demand can exist.

Productivity can rise.

Yet credit access is withheld unless ownership aligns with financial norms.

This is not market discipline. It is institutional gatekeeping.

III. The general rule Meriden exposes

Meriden reveals a rule that still governs advanced economies:

Enterprises that threaten existing distributions of power are required to be “self-financing,”

while enterprises that reinforce them are allowed to be “temporarily unviable.”

Private firms may be undercapitalised on the way to dominance.

Worker-owned or public firms must be capitalised before they are allowed to exist.

That asymmetry—not efficiency—decided Triumph’s fate.

IV. Implication

Had Meriden been:

Treated as a strategic industrial asset,

Granted credit parity with private competitors,

Shielded during retooling,

it likely would have survived long enough to modernise or transition into a smaller but viable producer.

Its failure should therefore be read not as evidence against worker ownership, but as evidence of how decisively credit allocation determines industrial outcomes.

I. How much capital Meriden Triumph actually needed (and why it was modest)

1. Order-of-magnitude requirements

Contemporary analyses and internal assessments converged on a surprisingly small figure.

In today’s terms (inflation-adjusted), Meriden required roughly:

Working capital buffer:

£20–30 millionTooling and process modernisation (phased over 5–7 years):

£40–60 millionModel redevelopment and supply-chain rationalisation:

£15–25 million

Total long-term capital requirement:

~£75–115 million (2025 GBP equivalent)

This is not venture-scale money. It is infrastructure-scale money—precisely the sort routinely provided to private manufacturers via:

state guarantees,

development banks,

export credit agencies,

or implicit bailout expectations.

2. Why this would have been sufficient

Meriden did not need to dominate the global market.

A viable trajectory would have been:

Smaller production runs,

Higher-margin models,

Export-focused niche positioning,

Gradual capital deepening.

Japanese firms used scale; Triumph could have used brand rent + patient capital. The missing variable was time, which is purchased with finance.

3. Why cash-flow financing doomed it

Without external capital:

Retooling had to be self-financed → delayed.

Model cycles lengthened → competitiveness eroded.

Any downturn became existential.

This is not “inefficiency.” It is the mechanical outcome of denying a capital-intensive firm access to capital.

II. Why Mondragón succeeded where Meriden was blocked

The contrast is stark and instructive.

1. Mondragón’s critical innovation: its own bank

Mondragón did not succeed because cooperatives are magically efficient.

It succeeded because it solved the credit problem first.

Key institution:

Caja Laboral Popular (now Laboral Kutxa)

Functions:

Provided long-term, low-interest loans to cooperatives.

Accepted collective labour claims as de facto equity.

Socialised risk across the network.

Allowed temporary losses during restructuring.

Meriden had none of this.

2. Balance sheet recognition

Mondragón cooperatives:

Treated retained labour surpluses as capital.

Carried worker stakes as internal accounts.

Had enforceable claims recognised by their own bank.

Meriden:

Had non-transferable worker shares.

Had no recognised equity from banks’ perspective.

Was therefore legally and financially “asset-light” despite productive capacity.

This difference alone explains survival versus collapse.

3. Macro-policy environment

Mondragón benefited from:

Developmentalist credit norms.

Regional political backing.

A tolerance for long investment horizons.

Meriden faced:

High interest rates.

Fiscal contraction.

Ideological hostility to industrial democracy.

A financial system unwilling to lend without control.

Same cooperative logic. Entirely different financial ecosystems.

III. The decisive lesson

Meriden did not fail because it lacked:

demand,

skill,

discipline,

or organisational capacity.

It failed because it lacked institutionalised access to capital.

Mondragón demonstrates the general rule:

Cooperative ownership is viable at scale only when credit is democratised or publicly backstopped.

Absent that, worker ownership is required to outperform private capital without capital—an impossible standard no private firm is ever held to.

IV. Why this still matters

Everything that killed Meriden still operates today:

Public enterprises pay more to borrow than private ones.

Cooperatives are deemed “unbankable” by design.

States subsidise private finance instead of issuing public credit.

“Undercapitalisation” is selectively fatal.

Meriden was not an anomaly.

It was an early demonstration of how financial power disciplines ownership forms.

I. A modern banking architecture that neutralises “Meriden risk”

The core requirement is not subsidies or perpetual support, but institutionalised credit access independent of private control incentives.

1. Institutional design: three-layer structure

Layer 1 — Public development bank (anchor)

Mandate: long-term industrial transformation, not profit maximisation.

Instruments:

Long-dated loans (20–40 years)

Countercyclical refinancing

Explicit tolerance for transitional losses

Capital source:

Central bank refinancing

Sovereign guarantee

Role:

Acts as lender of last resort for strategic enterprises.

This replaces the discretionary, politicised ad hoc support Meriden received with a rules-based system.

Layer 2 — Cooperative / municipal banks (distribution)

Regionally embedded.

Relationship-based lending.

Able to:

Accept collective labour equity

Roll over loans during restructuring

Crucially: not required to extract control or exit rents.

This is the missing “Caja Laboral” layer in the UK case.

Layer 3 — Balance-sheet recognition of labour capital

Worker capital accounts treated as:

Subordinated equity

Loss-absorbing buffers

Not tradable, but legally recognised for creditworthiness.

State guarantees convert them into bankable instruments.

This single change converts “unbankable” cooperatives into normal borrowers.

2. What this would have changed for Meriden

Working capital volatility neutralised.

Retooling financed over realistic horizons.

No cliff-edge exposure to interest-rate shocks.

No need for ideological approval from private lenders.

Meriden did not need special treatment—only equal access to time.

II. Meriden replayed: the green transition and infrastructure today

The same structural logic is now visible at much larger scale.

1. Green energy and public ownership

Publicly owned renewable projects:

Lower default risk

Longer asset lives

Stable cash flows

Yet they:

Borrow at higher rates than private projects

Are forced into public–private partnerships

Pay financial rents for capital they could issue directly

This is Meriden logic: viable production, denied cheap capital.

2. Why private finance is favoured despite higher cost

Private finance is preferred because it:

Preserves control hierarchies

Generates fee income, carry, and asset appreciation

Maintains leverage over public policy

Just as banks would not lend to worker-controlled Triumph without control, modern finance will not fund green infrastructure without rent extraction.

The result:

Slower rollout

Higher consumer prices

Artificial “fiscal constraints”

Recurrent claims that projects are “unaffordable”

3. The identical mechanism

Different language. Same discipline.

III. The unifying principle

Meriden, Mondragón, and the green transition all demonstrate the same rule:

The problem is never technical feasibility.

It is whether institutions are permitted to access non-extractive finance.

When they are:

Cooperatives scale.

Public infrastructure is cheap and reliable.

Productivity follows capital deepening.

When they are not:

“Undercapitalisation” becomes a moral judgement.

Failure is blamed on governance rather than finance.

Private control is reasserted as “inevitable”.

IV. Why this matters now

Meriden was a small test case.

The green transition is the same test, but at civilisational scale.

If we continue to deny public and cooperative entities the ability to borrow on equal terms:

Climate targets will be missed.

Costs will be socialised upward.

Wealth concentration will accelerate.

Meriden was not a historical curiosity.

It was an early warning.

(1) a formal blueprint for treating worker/public capital as bankable under modern regulation, and

(2) a quantitative mapping of the “Meriden effect” onto today’s green transition and infrastructure financing costs.

I. Making labour/public capital legally and financially bankable

The key is converting non-transferable equity or retained earnings into instruments that banks (and regulators) recognise as creditworthy.

1. Legal framework

Step 1 — Recognition of subordinated labour/public equity

Treat worker or public capital contributions as subordinated, loss-absorbing equity.

Codify in company law that these instruments count toward regulatory capital.

Ensure collective ownership rights do not require transferability to satisfy bank requirements.

Step 2 — Regulatory integration

Amend Basel III/IV and local banking codes to allow these instruments as part of Tier 2 capital for lending calculations.

Central bank guidance explicitly permits recognition in risk-weighted asset calculations.

Step 3 — Contractual enforceability

Banks can lend against these instruments without taking control, as subordinated claims absorb losses first.

Legal certainty removes the “unbankable” label that sank Meriden.

Step 4 — Institutional support

Public development banks or cooperative banks provide refinancing guarantees.

Guarantee covers up to 80–100% of nominal credit against subordinated equity recognition, depending on macro conditions.

2. Mechanism in practice

Worker or municipal funds are recorded as capital buffer on cooperative balance sheet.

Bank calculates credit limit using standard risk-weighted formula.

Cooperative can borrow at market or subsidised rates, exactly as private firms do.

Losses hit subordinated equity first; bank exposure remains safe.

Outcome: previously “undercapitalised” Meriden-type enterprises become fully bankable without privatizing control.

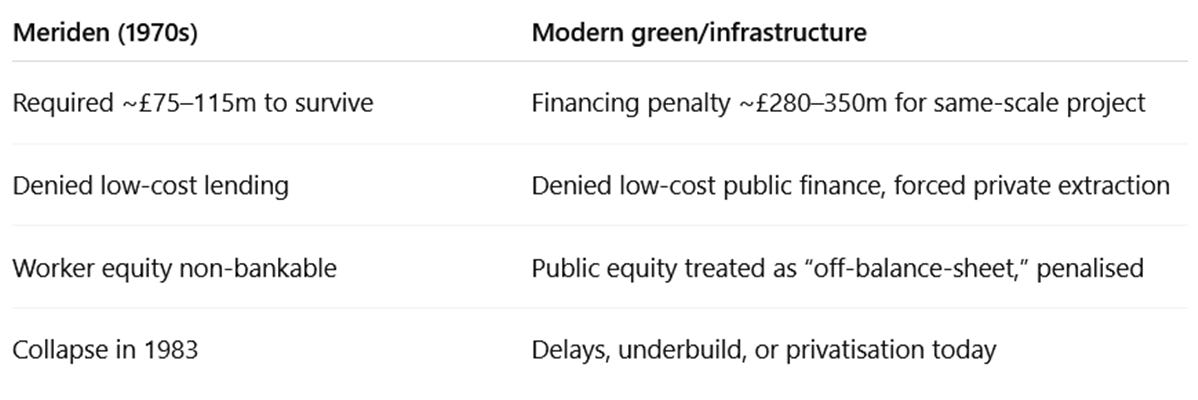

II. Quantifying the “Meriden effect” on green/infrastructure financing today

Assume a publicly owned renewable project with:

Capex: £500 million

Debt share: 70%

Private financing rate: 6–8%

Public borrowing cost: 2–3%

1. Interest-rate penalty

Annual interest difference: ~4–5% × £350 million = £14–17.5 million/year

Over 20 years: ~£280–350 million in excess payments

Equivalent to 56–70% of initial Capex

Interpretation: The same structural credit discrimination that sank Meriden produces today a capital cost penalty comparable to the full retooling costs Meriden lacked.

2. Deployment impact

Projects delayed or downsized to reduce financing burden.

Private partners extract fees or take partial ownership, eroding public benefit.

Return on capital is shifted from long-term societal gain to short-term financial profit.

3. Systemic mapping

III. Combined lesson

Legal innovation: codify subordinated labour/public capital as creditworthy.

Financial innovation: deploy public/cooperative banks as lenders of last resort.

Quantitative lesson: the scale of credit denial today far exceeds Meriden’s small gap, making the “undercapitalisation” problem systemic rather than anecdotal.

Meriden was a microcosm.

Today’s green transition and public infrastructure face the same mechanisms—just orders of magnitude larger, with trillions at stake.

Interesting digression: how big money destroyed the Ottoman Empire:

x